The Intertribal Agriculture Council, along with its partners, is a finalist for the Racial Equity 2030 Challenge, a global call to advance racial equity in the next decade. Using Indigenous regenerative practices, they’re working to disrupt the food financing and agricultural systems to increase access to traditional healthy foods and wealth generation opportunities for all Indigenous people.

“We do this work so future generations of Indigenous people will inherit opportunity, not inequity.”

Kelsey Ducheneaux-Scott

Kelsey Ducheneaux-Scott has a vision for Indian Country rooted in the resilience of her Lakota people. She envisions integrative and resilient local food systems that weave together ancient and contemporary practices to regenerate land and community. The Lakota people humbly acknowledge their part in the living systems that sustain us all. It is through this cultural awareness and the knowledge imparted by her ancestors that Kelsey designs solutions locally and across Indian Country.

Her passion stems from a desire to contribute to the restoration of what was lost through 250 years of federal annexation of Indian lands and perpetual genocide. Kelsey promotes the reconnection of American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) communities to their lands and foodways to cultivate community-based solutions designed by local food producers.

“Our Regenerative Finance Model will allow us to ensure a redistribution of wealth to the communities that have long been stripped of access to it,” says Ducheneaux-Scott, director of programs at the Intertribal Agriculture Council (IAC).

As part of the W.K. Kellogg Foundation’s Racial Equity 2030 challenge, IAC will implement solutions to address the extractive agricultural and financial systems that starkly limit the capacity of Tribal communities to preserve their foodways. IAC’s solutions directly respond to the existing racist lending system that furthers the outgrowths of colonialism, which include chronic poverty and disproportionate outcomes across Indian Country.

The Situation

Hunger and food insecurity are prevalent in Indian Country. According to a report by Northern Plains Reservation Aid, Native American households are 400% more likely to report food scarcity than the general population. Food and credit deserts across the United States overlay with Indian Country almost exactly. According to the Indian Health Clinical Reporting System, more than 80% of AIAN adults ages 20 to 74 are overweight or obese. Between 45% and 51% of children and youth are not at a healthy weight, and childhood obesity rates often exceed 50% in Tribal communities. Native Americans also experience high rates of tooth decay, diabetes, heart disease and suicide.

“This is driven by the displacement of our people from the healthy foods that sustained us,” says Ducheneaux-Scott. The extractive agricultural system Tribal nations were forced to adopt “had a devastating impact on the health of the people and the land, however, our communities hold the key.”

As alarming as these statistics may be, oftentimes, deficit narratives “about” Indian Country state the disproportionate rates of food access and nutrition-related issues, assigning Native communities to a status of desperation without adequately featuring the inherent assets, determination and resiliency of AI/AN peoples. Dating back to contact, colonization and forced dependency have been the primary factors at play in creating the inequities facing Native communities. Native peoples in the Americas have been violently forced to drop the foodways that sustained them for thousands of years.

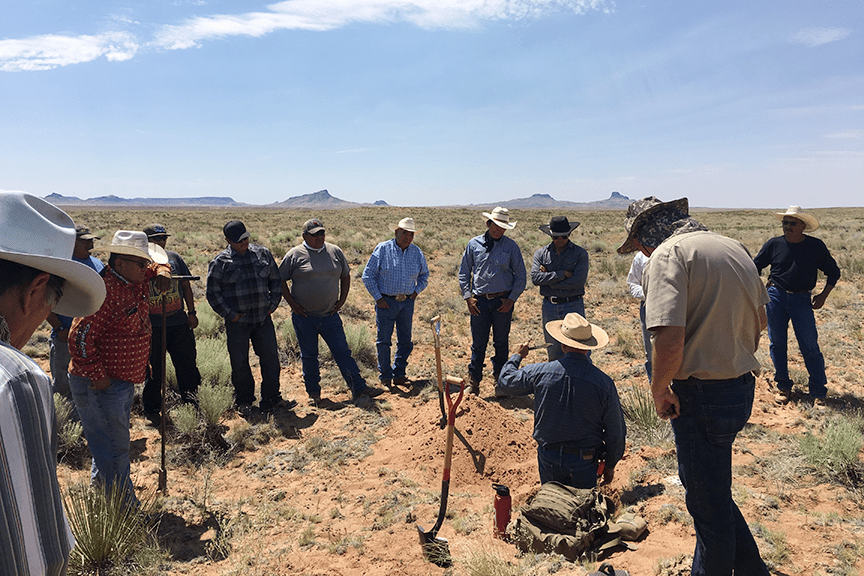

Long before boundaries were drawn for reservations, AI/AN nations employed regenerative agricultural practices that didn’t limit them to a particular part of land or a singular crop. Through hunting, foraging and farming, they sustained an Indigenous food system that produced all the nutritious food their communities needed.

The reservation system ended that, making it nearly impossible – even today – for AI/AN people to produce the food needed to sustain their communities. To make a living or pay back high-interest loans, they must produce and sell food to auctions, food processors and major food companies off-reservation, externalizing the benefits of locally produced nutrition.

“This robs our communities of local supplies of healthy foods and keeps our food insecurity rates disproportionately high,” says Ducheneaux-Scott. The result is that more than a quarter of Native people rely on the U.S. government for food assistance. That food rarely includes the nutritionally dense staples of many Tribal diets, instead providing canned fruit and vegetables and powdered milk and potatoes.

The Reservation Era

Between 1850 and 1887, in what historians refer to as “The Reservation Era,” the United States federal government systematically drove Native Americans from their homelands, relegating them to a reservation system that continues to inflict irreparable harm on Native Americans today.

Game-Changing Solution

The IAC and its partners have three overarching goals for all 574+ AI/AN Nations: disrupt the food and agriculture finance system; increase access to traditional and culturally appropriate foods for all Indigenous people; and remove the political barriers that make it hard for Indigenous people to generate wealth.

Success hinges on IAC’s new Regenerative Financing Model (RFM). The RFM provides Tribal producers with access to capital at flexible terms to produce the food needed for their families and put profits back into the community. “The RFM not only replenishes the landscape, but it returns the very wealth that was once stolen from Indigenous communities as colonizers pulled the levers of power in a way that benefitted only a select few,” says Ducheneaux-Scott. “With the RFM, we are pulling that lever back in our favor.”

In the current system, Native producers are at an extreme disadvantage in seeking fair credit. Their land is remote, making market access difficult. Most banks won’t lend to Native food producers because they do not “own” the land. When reservations were created, the federal government did not provide deeds to the land. Most commercial lenders won’t consider the land as collateral in the loan application process.

“There’s discrimination that happens in that space that prohibits [Native] producers from being able to access the financial capital they need to develop or diversify their operation well,” says Ducheneaux-Scott. Unable to obtain significant loans from these lenders, Native producers have smaller budgets than other producers and are susceptible to predatory lending practices.

One of the few sources of capital that Native producers can turn to are Native Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs). There are 69 Native CDFIs, and the amount they can lend is dependent on the amount of capital they themselves can secure. “Our Native CDFIs are not afraid to be in Indian economies,” says Ducheneaux-Scott. “They value and appreciate the culture that exists within our economy and they’re willing to fill the need that other lenders associate as risk.”

Bold Steps Toward a Thriving Indigenous Economy

Over the next eight years, IAC and its partners will take steps to build a thriving economy rooted in Indigenous, regenerative practice. Specifically, they will:

- Employ the RFM to grow Native food and agriculture economies by $20.4 billion;

- Design open markets with demand for Native food products;

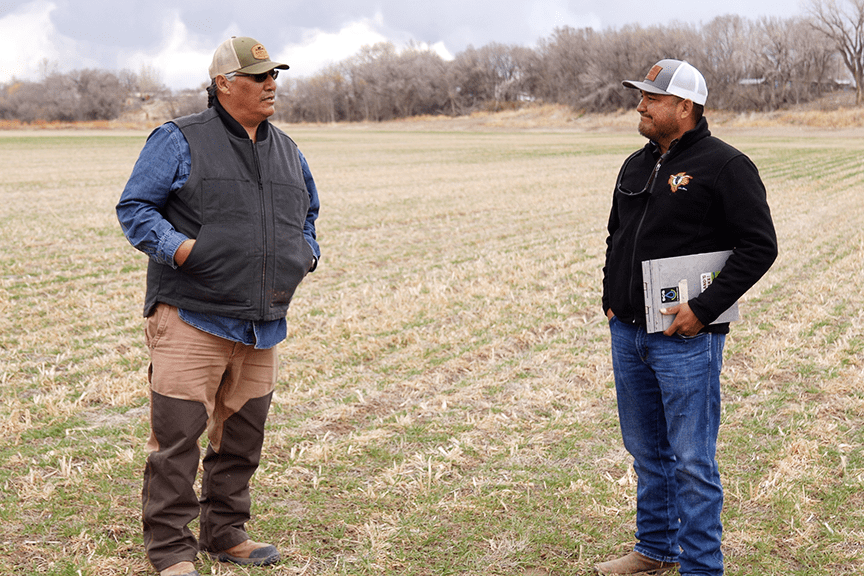

Provide individualized technical assistance to more than 80,000 food producers; - Embrace traditional ecological knowledge of Indigenous stewardship across more than 78 million acres of land;

- Empower 10,000 Native American young professionals to pursue careers in food and agriculture;

- Demolish and transform the political barriers that have systematically oppressed Indian Country for centuries.

The IAC is working with Tribes to reclaim foods that were historically part of their diet. IAC helped food producers in the Great Lakes region grow and harvest wild rice to meet U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) safety standards and size requirements. Although Native Americans grew wild rice for centuries, the government would not include it in the USDA Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR) until it met certain specifications. Only now is it recognized as a replacement for powdered potatoes.

Restoring What Was

By 2030, Ducheneaux-Scott envisions Indian Country to be on a path towards the same food sovereignty that her ancestors stewarded. “And there are tribes already well on their way!” Kelsey exclaims. “Just down the road, the Rosebud Sioux Tribe (located in present-day South Dakota) is a great example of community initiatives making strides towards this reality.”

The tribe created a culturally driven effort housed in their economic development corporation to help achieve food sovereignty. Their efforts thus far have included starting a community garden and collaborating with the local Tribal college to create a curriculum centered on gardening and identifying the food staples that Indigenous communities can access on the land, such as wild turnips, wild onions and berries.

The Rosebud Sioux Tribe also built a shared geo-dome greenhouse at the heart of their community garden to house discussion and learning. This has contributed to the rekindled conversation around the tribe’s cultural connection to food and has since grown into a thriving outdoor education center.

“All of our Tribal communities took an approach that was unique to their cultural value systems but was always mindful of how we interacted with all that surrounded us,” says Ducheneaux-Scott. “We want to bring a respect for this resourcefulness back to the forefront of conversations in philanthropy.”

Related Links

Mobilizing 50,000 Indigenous women for change

Caretakers of the Earth: An Indigenous-led movement to secure land rights

Healing through action

Eliminating the Latino Opportunity Gap

Restaurant workers are standing up for increased wages – and racial and gender equity

Native Hawaiian-centered approach helps youth heal and become healers

In Brazil, a movement to unleash the world’s first anti-racist education system

Comments