Partners in Development Foundation, together with an assembly of local partner organizations, is a finalist for Racial Equity 2030, a global challenge to advance racial equity in the next decade. Together, they’re working to end youth incarceration, especially of Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander youth, in Hawai’i.

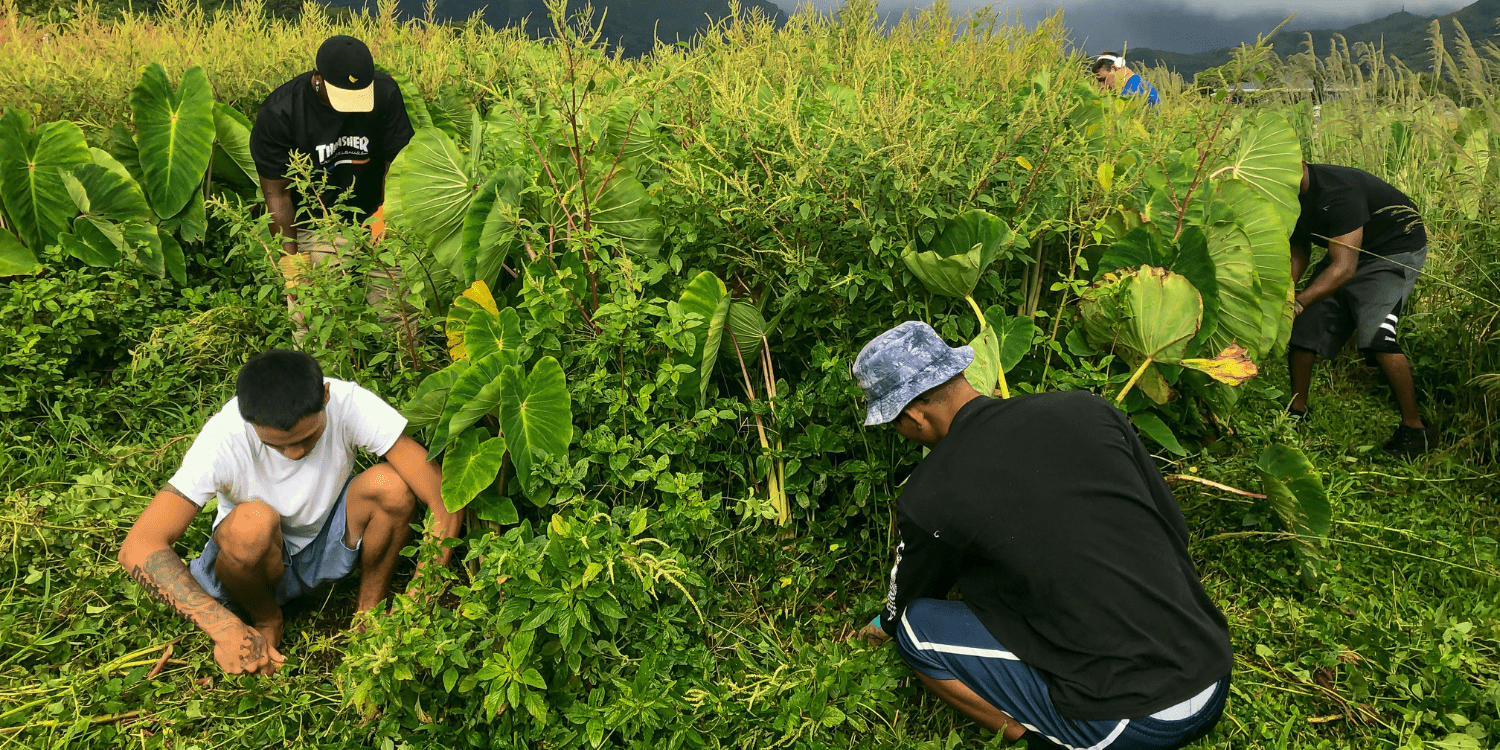

When teens and young adults first walk onto the fields of Kupa ʻAina Natural Farm, Zachary Huang doesn’t expect much from them. He knows it could be days before they talk or show any interest in the 5-acre farm that sits high on the hills of Oʻahu.

He doesn’t push. He knows they need space.

By the time they reach Kupa ʻAina, these youth have been in survival mode for most of their lives. They’ve been caught up in a series of broken systems that have left many generations of Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders (NHPI) in an enduring cycle of poverty and trauma.

To break that cycle, the State of Hawaiʻi joined forces with the Partners in Development Foundation in 2020 to create an alternative to the state’s youth incarceration system and provide them with the community support so many of them never had.

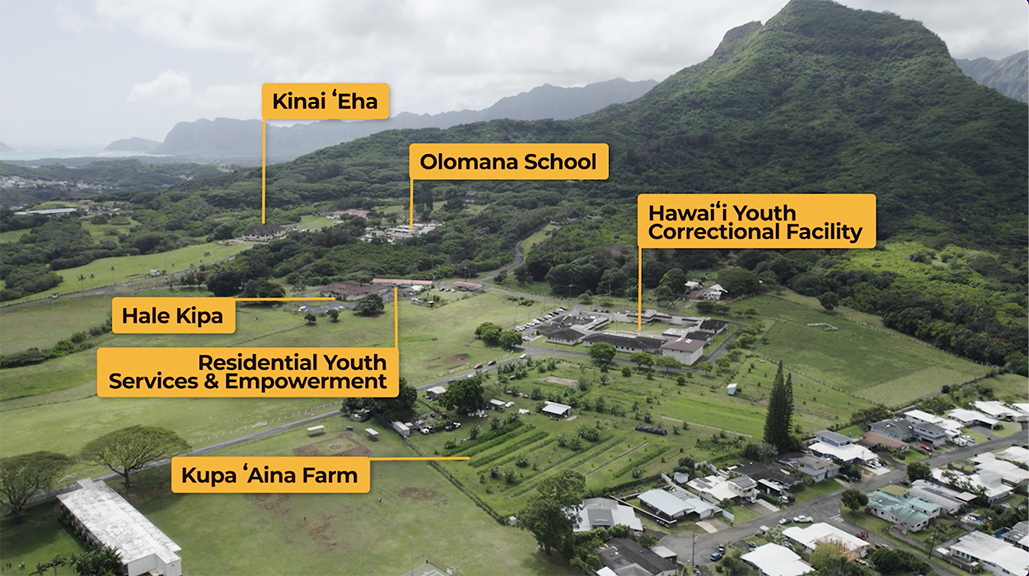

To this end, the state partnered with several nonprofits to form an assembly called, Opportunity Youth Action Hawaiʻi (OYAH), to offer wraparound services at the Kawailoa Youth and Family Wellness Center – the 500-acre campus that is home to Kupa ʻAina Farm, the Hawai’i Youth Correctional Facility and a number of other youth service providers. The growing group of partners that make up OYAH are dedicated to using Hawaiian knowledge and cultural practices to help youth heal and find their way forward.

“A lot of the youth that we work with might be in their 20s, but they've been on the streets since they were 13 or 14,” says Huang, program director of Kupa ʻAina Farm. “They can’t put down their survival coping mechanisms until they’re no longer concerned about food, water or shelter.”

So, Huang waits. When they start to play in the fields, Huang knows they are ready to listen, to start talking about the hard things, to begin the process of healing from trauma.

“You have to meet them where they’re at,” says Huang. “You can’t force them to be somewhere or to do something. That would just re-traumatize them.”

For some participating youth, the farm offers a chance to heal and thrive that does not rest in a 4 x 8-foot cell at the Hawaii Youth Correctional Facility or out on the streets. That chance is at the heart of Kawailoa.

As part of the W.K. Kellogg Foundation’s Racial Equity 2030 challenge, OYAH proposes a bold, multi-year initiative to end youth incarceration in Hawaiʻi by 2030, replacing it with cultural and therapeutic programs aimed at healing.

The Situation

Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders are disproportionately represented in the youth justice system. They face hurdles unimaginable to other teens and young adults in Hawaiʻi, experiencing the highest rates of involvement in foster care, child welfare, mental health services, special education and family court. Many are invisible in their own communities.

According to the Office of Minority Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Native Hawaiian youth:

- Represent 47% of all minors in the state who do not have a place to call home;

- Comprise one-third of the state’s youth population but over half of the youth in the prison system;

- Account for more than half of those transitioning into adulthood from foster care, often with no place to go;

- Are three times less likely than non-Hispanic Whites to receive mental health services;

- Are often vulnerable to and often die by suicide – it is the leading cause of death for this age group.

They receive longer sentences for petty crimes and are more likely to experience substance abuse, trauma, loss of loved ones, broken relationships, depression, human trafficking and economic instability. The services meant to support them are fragmented and hard to access due to frustrating barriers.

A Different Approach

That is why OYAH centers on supporting youth with aloha, which confers love, compassion and equity, allowing them to heal and to find purpose and meaning. Aloha is much more than a greeting. It is a practice. And, for Native Hawaiians, aloha is a deeply generative force that leads to equality and mutual respect.

Kawailoa houses state agencies and community-run programs on campus. As part of OYAH, partners cultivate an ecosystem of support to provide reciprocal learning between youth and adults, as well as housing, workforce training, employment, and trauma-informed care for young people.

OYAH works intensely to serve roughly 300 young people a year and plans to double that number to 600 as it expands partnerships across the state. The group focuses on NHPI and BIPOC youth ages 14-24, teaching them to embody aloha and become healers, so they can give back to the community.

“These are the kids who fall through the cracks,” says Carla Houser, executive director for Residential Youth Services & Empowerment (RYSE), one of the non-profit partners, which helps homeless young adults find temporary housing. “They’ve either aged out of foster care or have been kicked out of their family home.”

Hawaiʻi has the second highest population of youth in the country experiencing homelessness yet little access to services like those offered at Kawailoa.

“We [RYSE] were running a drop-in center in Waikīkī, providing all these amazing services,” says Houser. “But every day at six o’clock, we would close the doors and send these kids back out onto the street.”

That changed when RYSE started its on-campus program at Kawailoa. The program puts a roof over youths’ heads and offers them a chance at stability. It is an example of the support that NHPI youth need to begin to heal. Offering a place of belonging improves their ability to move forward and pursue their dreams.

Houser understands what young Native Hawaiians are up against. “Twenty years ago, I lived this life,” she says. “The only reason I got out was because I had trusting adults who didn’t judge me.”

Stopping History from Repeating Itself

In 2014, a state-appointed Juvenile Justice Reform working group concluded that Hawaiʻi’s juvenile justice system did little to reduce crime, failed to rehabilitate most justice-involved youth, and had a recidivism rate of 80 percent for Native Hawaiian and BIPOC young adults — compared to 60 percent for the rest of the population.

In 2018, the legislature mandated that the state replace its punitive youth confinement system with a coordinated system of supportive wraparound services, including rehabilitation and community re-entry programs. Within months, community leaders and partners launched an intensive community engagement process that generated Kawailoa’s 10-year Programmatic Plan to transform Hawaii Youth Correctional Facility and the surrounding land into a healing sanctuary that can serve as a model for marginalized communities worldwide.

A Journey Toward Healing

Machijah’s journey is evidence that the plan is working.

Close to two years ago, Machijah, who has spent much of his young life shuttling from home to home, was placed on campus at RYSE. He started his healing process by working four hours a day, two days a week. As he progressed, Houser helped him secure a full-time internship through a partner agency. Kupa ʻAina Farm hired him and helped him establish stable housing.

“He’s been with us almost one and a half years now,” says Huang. “He now helps his mother and his girlfriend. I’ve seen this again and again. Once these youth stabilize, they start to thrive. And they turn outwards to help their friends, their families.”

A Hawaiian proverb, shared by Hawaiian scholar Mary Kawena Pukui, states: “Mōhala i ka wai ka maka o ka pua,” meaning, “unfolded by the water are the faces of the flowers.” This is interpreted as, flowers thrive where there is water, as thriving children are found where living conditions are good. Like so, OYAH provides the conditions for young people to blossom. In the process, they are breaking intergenerational cycles of poverty and incarceration. “They become conduits to change the family dynamic,” says Houser. “They work with us to become healers within their families and within the community.”

Game-Changing Solution

OYAH aims to increase well-being for young people and reduce disparities for NHPI communities and others disproportionately impacted by the justice system. By 2030, OYAH will:

- End youth incarceration in Hawaiʻi, replacing the punitive corrections system with cultural restorative programs

- Double the number of youth participating in Kawailoa campus programming from 300 to 600

- Build a statewide network of care for justice-involved youth across island communities, organizations and agencies

- Establish a residential mental health treatment center in Hawaiʻi

- Elevate the state’s youth as racial equity leaders

- Generate a worldwide movement to replace youth incarceration with Indigenous healing practices

“Today, there are more Native Hawaiians in L.A. County than in Maui,” says Houser. “If we don’t create these supports, we’ll continue to see an exodus of young people who belong here. When they leave, we lose the culture, the language.”

Like elsewhere in the United States, the number of young people in need of mental health services continues to grow. But there are no local mental health centers for NHPI and other youth in Hawaiʻi. The state sends about 40 young adults to the mainland for mental health services annually. This has led to an outcry from parents to keep them home, and to OYAH’s plans to break ground on a mental health care center at the Kawailoa campus.

Hope

“Native Hawaiian culture and people define Hawaiʻi,” says Mark Kawika Patterson, who oversees the Hawai’i Youth Correctional Facility at Kawailoa. He fears that the culture could be lost within a generation if the youth don’t have what they need to heal themselves and their communities.

“Kawailoa represents hope,” says Patterson, who wants the youth to thrive but always know they can return to the Kawailoa campus whenever they want. “We provide them with the hope that their day-to-day existence can change.”

At Kupa ʻAina Farm, youth are learning to laugh and connect with the land. They are finding purpose. They could be the ones to continue working the land when the current generation of 60- and 70-year-old farmers retire and strengthen the roots of the culture that they are rediscovering.

Related Links

Mobilizing 50,000 Indigenous women for change

Caretakers of the Earth: An Indigenous-led movement to secure land rights

Healing through action

Eliminating the Latino Opportunity Gap

Regenerating food and agricultural finance systems in Indian Country

Restaurant workers are standing up for increased wages – and racial and gender equity

In Brazil, a movement to unleash the world’s first anti-racist education system

Comments