This post is also available in: Español (Spanish) Kreyòl (Haitian Creole)

When a 7.0 magnitude earthquake struck Haiti on Jan. 12, 2010, causing mass casualties across the capital region, there was not a single Haiti-trained emergency physician in the country. With no formal medical education programs in emergency medicine, Haitian clinicians interested in studying the specialty would have to go elsewhere.

As images of the 2010 earthquake circled the world, Haitian and foreign medical professionals of various specialties responded as they were able, saving countless lives. Yet, countless more could have been saved had a team of Haitian emergency physicians been on the ground when the earthquake struck.

In the intervening years, life in Haiti has grown more difficult, yet when a 7.2 earthquake struck the country’s southern peninsula in August 2021, it revealed an improvement in the domestic medical response capacity from a decade before.

Dr. Jean Jimmy Plantin is part of this positive change. At the time of the January 2010 earthquake, Plantin was working in northern Haiti, far from the earthquake epicenter. He remembers medical assistance arriving from overseas, including from the U.S. Naval Ship Comfort, a 1,000-bed floating trauma hospital. But as far as life-saving care in those critical first hours, Plantin says, “I believe that Haiti was not prepared, and we didn’t have a response that was adequate.” One of the problems: “We didn’t yet have trained emergency doctors in the system.”

The rebuilding phase that followed, as international news outlets reported at length, was uncoordinated, with only a small fraction of donor funds reaching Haitian public and private organizations. Despite the billions of dollars pledged for reconstruction, little materialized in housing and infrastructure.

However, where post-2010 investments were guided by local expertise, they yielded some noteworthy progress. One example is Hôpital Universitaire de Mirebalais (HUM), a health facility run by Zanmi Lasante (ZL), the Haitian sister organization of Partners in Health (PIH), with the Haitian Ministry of Health.

Teaching hospital provides “inspiring” emergency care after latest disaster

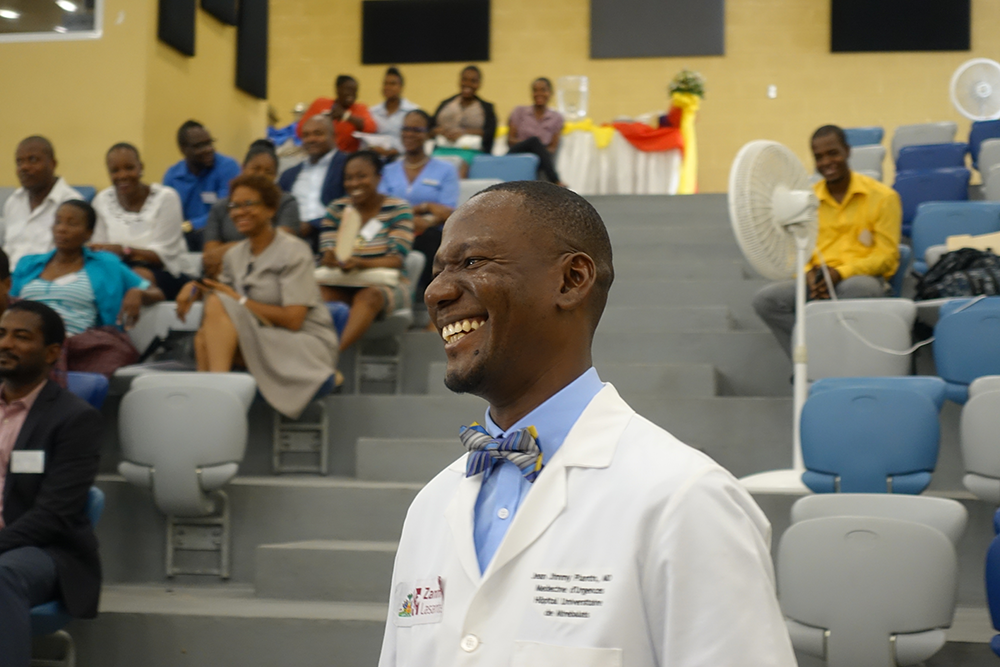

The vision for the hospital dates back more than three decades, but it broadened in scope and ambition after the 2010 disaster. More than 100 funders, including the W.K. Kellogg Foundation (WKKF), rallied behind the plans. In 2013, the 300-bed state-of-the-art teaching hospital opened to the public to provide free medical care. HUM went on to establish medical education programs in pediatrics, family medicine, obstetrics/gynecology, internal medicine, general surgery and emergency medicine. In 2014, Plantin became one of just four medical residents in the first class of Haiti’s first emergency medicine training program.

Plantin had already regularly cared for patients in emergency settings in Haiti, but as a general practitioner. When he had the opportunity to work alongside two emergency physicians from the U.S., he was excited to learn new methods of rapidly identifying and addressing potentially life-threatening conditions.

“I developed a certain love for the practice of emergency medicine,” he said. So, when the training program began at HUM, “It was a great opportunity. I was really proud that I made that choice.”

Plantin graduated in 2017 and began using his newly acquired skills in HUM’s busy emergency room, treating patients with traumatic injuries and in cardiac and respiratory distress. The greatest test so far came on Aug. 14, 2021.

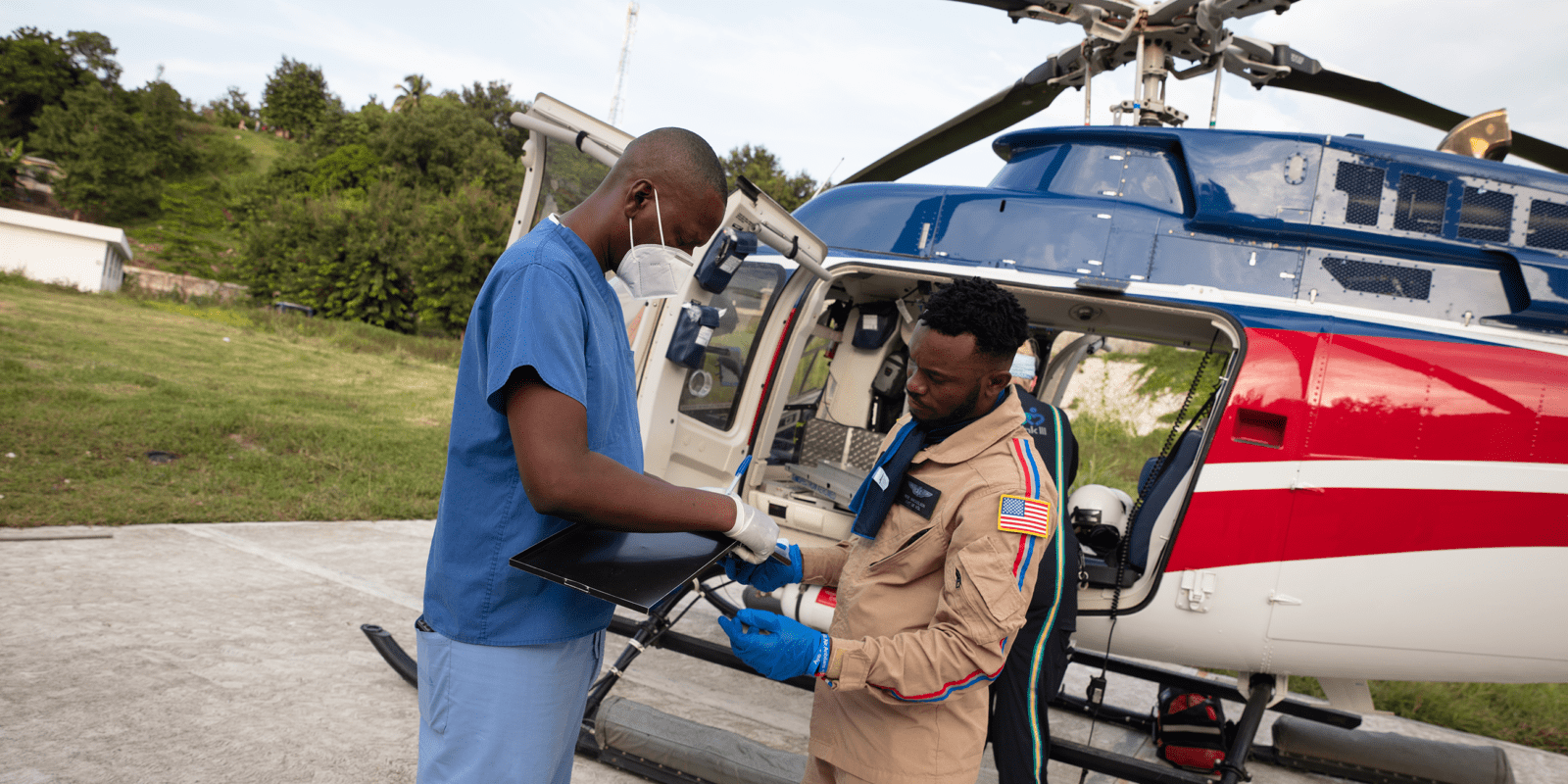

“Immediately after hearing that there had been an earthquake, I reached out to the head of emergency medicine at HUM to see what we could do,” he said. The staff started preparing to deploy teams to the affected area, and within days, earthquake survivors began arriving at the hospital by helicopter.

Over the following weeks, as doctors from HUM deployed to the earthquake zone and St. Boniface Hospital, another WKKF grantee, to treat the injured, Plantin led the team at HUM’s emergency department in treating dozens of medically evacuated patients.

In an interview with the Harvard Gazette, PIH co-founder Dr. Paul Farmer described Haiti’s first class of emergency medicine doctors’ response to the 2021 earthquake as “downright inspiring.”

“I think it was a very good experience,” Plantin said. “We did not have a lot of resources to be able to act in several spaces at the same time, but the training allows us to respond to these kinds of things. I think we have a team that’s solid, that’s determined. …When there’s a need, we’re ready to help.”

Plantin was particularly moved by a patient who arrived at HUM four days after the earthquake with a fractured limb. Untreated for days due to lack of capacity at health facilities in the earthquake zone, the man’s leg was operated on within two hours of arrival at HUM.

It was a point of pride that HUM’s medical team was able to respond so quickly, Plantin said. On the other hand, he said, “That clearly demonstrates the problems in the healthcare system and also how we need to take action to improve the structure, improve access to care and improve the personnel in terms of having staff who are qualified to treat those patients.”

Investment opportunities for the future of healthcare in Haiti

HUM is a success story of post-2010 earthquake investment and coordination. The hospital now hosts five medical residency programs (and ZL runs a sixth at Hôpital Saint Nicolas, in St. Marc, Haiti), and in 2020 HUM became the first medical institution in the Western Hemisphere to receive accreditation from the international arm of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME-I).

Since the 2021 earthquake, the eyes of the world are far less fixed on Haiti’s recovery than they were in 2010, which is reflected in low levels of relief support. But that doesn’t stop Plantin from imagining what’s possible.

One dream of his, he says, is that, “In the next 10 years, every emergency room in the country have at least one doctor who specializes in emergency medicine.” His other dream: “that there be a permanent structure that has various specialists – not just emergency physicians, but surgeons, orthopedists, anesthesiologists and engineers, too, who make up a sort of battery of people who are ready to act, in each zone of the country, so when something happens, a natural disaster, the group closest to it will react, before backup can arrive.”

Today, it is difficult to think about the future when the present is so difficult to manage. Among the litany of challenges – which include a political vacuum, rising food insecurity, and gang violence, perhaps the most acutely felt at hospitals is a fuel shortage that’s impairing institutions largely dependent on generators for electricity (as solar power remains an area too often overlooked by donors).

Nevertheless, Plantin is not leaving his country. Neither will 98 percent of HUM’s residency program graduates – an extraordinary statistic given the high rate of emigration by educated Haitians. Plantin says he wants to stay to be part of the construction of a better Haiti.

“I believe we gave ourselves an objective,” Plantin says, “and we have to fight to attain that objective, which is to assure that the patients, Haitians like us, find quality healthcare even if they don’t have much money.”

Featured Image: Dr. Jean Jimmy Plantin during the 2021 earthquake response. Credit: Nadia Todres

Comments