This post is also available in: Español (Spanish) Kreyòl (Haitian Creole)

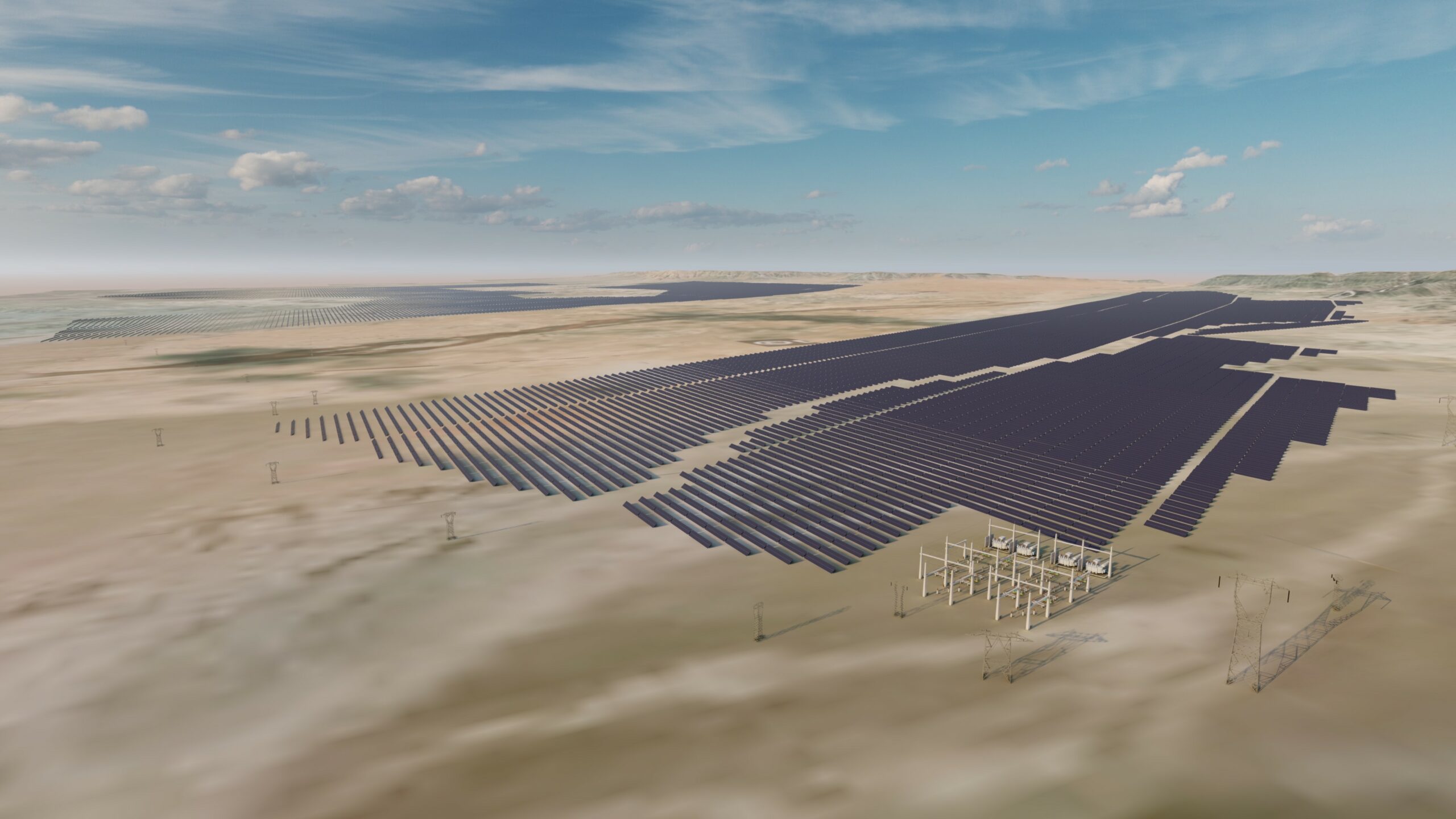

Navajo Power, a public benefit corporation, works with Native-owned organizations to develop utility-scale clean energy projects and is reinvesting 80% of profits into new infrastructure projects and community benefits.

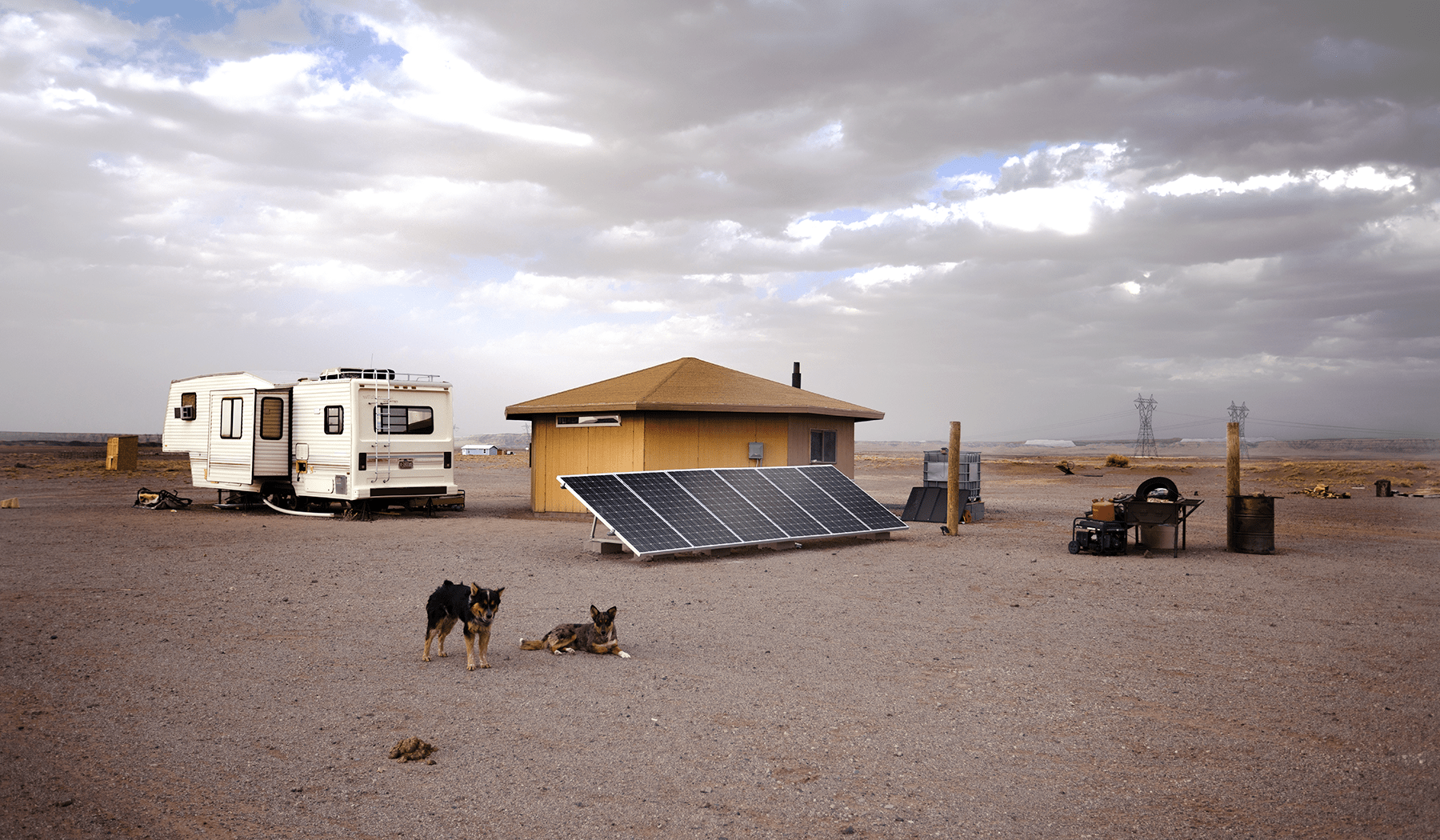

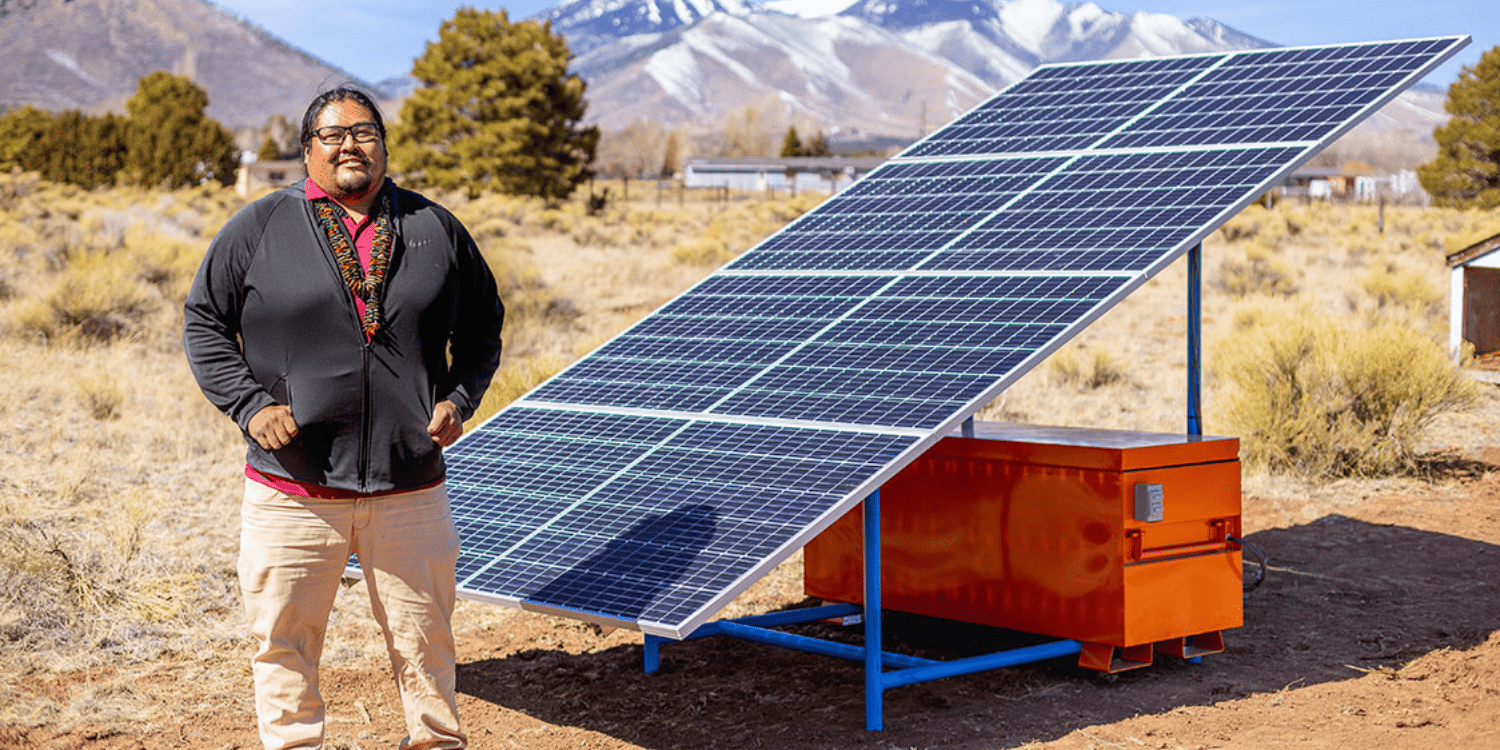

Over the next decade, Navajo Power aims to deliver billions of clean energy infrastructure assets to power major markets across the U.S., with emphasis on the Southwest. A subset of this work includes bringing electricity to Navajo Nation households, where 15,000 families lack access to electricity. Navajo Power has launched a separate company, Navajo Power Home, to focus on this work of bringing power to Navajo families directly.

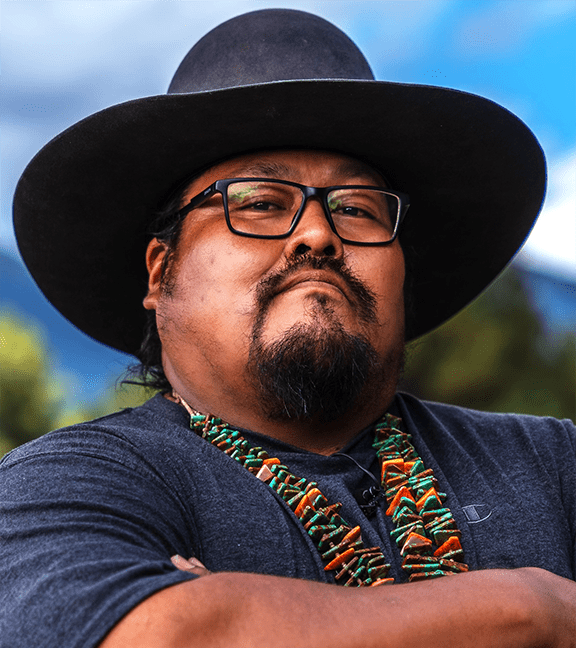

The W.K. Kellogg Foundation’s (WKKF) communications team met with Brett Isaac, Founder and Executive Chairman of Navajo Power, and Co-Founder Clara Pratte to discuss the corporation’s beginnings, its vision for clean energy projects on Tribal lands and the impact of a $3 million program-related investment (PRI) received from WKKF earlier this year.

Tell us about the early development of Navajo Power.

Brett Isaac: Navajo Power was born out of a bit of frustration and necessity. I made friends with Dan Rosen [co-founder of Navajo Power], who came to the Navajo Nation to advocate for preservation of water and at the same time, he learned about the inequity in energy access. We were at a ceremony for the daughter of a family friend; she was having a coming of age, a Kinaaldá in Navajo. Dan and I had the task of watching the fire. At night you talk about all kinds of things, making sure the fire stays at a certain level and drinking coffee. Late in the middle of the night, we were looking above the valley, where the coal train goes from the Peabody Coal Mine to the Navajo Generating Station. There were rumblings that they wanted to close the plant. We returned to the same conversation: “what do we do?”

We knew the economics were not one-to-one; there’s no plan where solar replaces a coal plant. Footprints, economics, the cost of energy are just too different. The rate of closures will only increase on fossil fuel facilities, and the companies that have traditionally procured power can easily exit any conversation about how to regenerate the communities. So, we assembled the team for Navajo Power knowing Tribes will need to be engaged with its leadership and decision-making.

Tell us more about the connection you see between Navajo life and resource extraction.

Brett Isaac: I grew up near the Peabody Coal mine; I had family members that worked there. It was seen as the economic driver of the region, an institution. The mining families seemed to make more money and have more things, but whoever worked for the plant – their family never saw them. They were working as much as they could; the pay was really good, but that mine also required an intense amount of workers to make it operate. They definitely put their families in a better financial position, but it was on their backs. It was really, really hard.

And there was no upward mobility. I didn’t see Navajos making it to the C-suite. We seek motivation for things we do if we can envision ourselves at the highest level. And at a young age, I asked myself: “Why aren’t we the ones? When is it our time?” We’re always seeking but never reaching – never able to make the better decisions on behalf of our people. I think we have the expertise. I think we have the talent. We’ve just been exporting it for years.

Our enterprises and our government weren’t set up for our benefit. The Navajo Nation was created for oil and gas leases; we didn’t have a government before someone needed someone to sign a document. Every deal had to be retroactively adjusted, because the deals were not fair.

With Navajo Power, we're not just creating opportunity; we're also trying to address and alleviate decades of traumatic experiences with energy. We’re responsible for reprogramming and rebranding how communities interface with energy development.

We wanted to dictate to the market: “if you want to develop in these communities, we’re going to set the bar at a level accountable to the people. If you want to come out here, you’re going to have to meet it. And if you do better than us, great! Then we’ve achieved exactly what we’re trying to do.”

Hear Brett describe the necessary but complicated opportunities with federal investments and clean energy.

Tell us about why native communities should be prioritized or among prioritized beneficiaries and stewards of federal and natural resources.

Brett Isaac: I mean, it’s our resources that built the country. It’s at our detriment. We’re not what we were. And the legacies of all these former industries – uranium, oil and gas, coal – are still harming our communities. One of the reasons COVID-19 had such a huge impact on the Navajo Nation was the preexisting asthma and respiratory problems in our communities because of energy extraction.

A debt is owed to our communities. One, to regenerate the economy they upended, but two, to address the impacts and footprints of what the federal government has done to leverage our communities for the benefit of metropolises. There isn’t talk about how the legacy of the former industries in its exit and in its wake will leave a lot of communities in bad shape. It’s not the markets that are really going to influence the speed of the transition; it’s going to be the incentives.

Can you give us an outline of how the program related investment from the Kellogg Foundation is going to support the work of Navajo Power?

Brett Isaac: One of the biggest barriers to development is access to capital, especially in pre-development. Philanthropic and federal programs build plans and assessments, but they don’t invest in the first steps needed for what it’s going to take to get there. Development is always considered significantly riskier than investing in something established.

The investment from the Kellogg Foundation through a PRI, has been a game changer for us. That kind of confidence in investing in those really careful next steps is needed for us to establish the mechanics of how to get to the next critical step, to be able to bring confidence to Tribes and Tribal communities that there are institutions out there that believe in the work. Mission aligned capital is one of the most crucial pieces needed in order for this transition to be successful. It sets the standard for how these transactions can be done. We can give other communities good guidance; “this is where the market is, this is what the tax regimes are in this part of the country, this is what made a successful project.”

Patient capital is another part of this. Traditional finance means operate on an accelerated timeline; the PRI allows us diligence. Creating that space for communities will ensure that they’re not doing decision making under duress.

Hear Brett describe how the Kellogg Foundation’s investment is impacting not only Navajo Power and the Navajo Nation, but entrepreneurship with Indigenous communities as a whole.

"We're working with the Kellogg Foundation on this idea that a Western transaction can have an Indigenous lens. It can be beneficial to and representative of these communities. We're not being asked to convert ourselves to something else. We're being supported in the work we're doing in the places we are."

Navajo Power was selected to participate in Apple’s 2nd Racial Equity and Justice Impact Accelerator cohort.

Comments