The United States faces a maternal and infant health crisis unlike any other industrialized nation where, as ProPublica reports, “severe complications during childbirth are skyrocketing.”

This crisis disproportionately impacts Black women and infants. Black women are three to four times more likely to die of childbirth related causes than White women and Black infants are twice as likely to pass away before their second birthdays.

Our partners in our priority places and across the country are working to make it safer and healthier for Black women to bring babies into the world. These grantees – and a growing body of evidence – tell us that these deaths are preventable and the crisis is solvable. The solution involves investing in Black women’s leadership and approaches that support birthing people, infants, healthcare providers and policymakers.

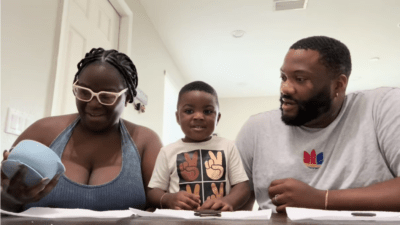

This story features a collaboration between Birth Detroit and the Institute for Medicaid Innovation (IMI), who are working to broaden options for maternal care in the state of Michigan – specifically the option to choose the midwifery model of care. Birth Detroit and IMI are both supported by WKKF.

Why midwives? Why now?

The word midwife means “with woman.”

For much of human history, every community included a wise woman who accompanied other women through the birthing process. Midwives are mentioned in the Bible and were present on the Mayflower. They were highly respected members of Indigenous communities and communities of African descent before, during and after slavery. As the keepers of the science of childbirth, midwives passed down their knowledge from generation to generation.

It wasn’t until the mid-20th century that giving birth in a hospital, attended by an obstetrician, became the norm.

“If we look at the history of obstetrics and midwifery in this country, there was deliberate and racialized legislation to take birth care out of the hands of midwives and place it into the hands of white male obstetricians,” says Leseliey Welch, co-founder of Birth Detroit and a public health expert.

The shift was set in motion in the 1920s by a series of regulatory actions that required costly training, certifications and licensures, and effectively took Black & Indigenous midwives out of the picture. At the same time, smear campaigns called midwifery barbaric and superstitious, changing many mothers’ opinions about the best way to give birth.

With a growing body of research showing that outcomes improve when midwives are integrated into maternal care, many women today are turning back to traditional ways, seeking the support of community birth workers to help them bring their children into the world safely. At the same time, Black women in cities across the country are leading the work to re-establish midwifery care in communities of color.

Unfortunately, for a substantial number of birthing people – the 42% covered by Medicaid – access to midwifery care is out of reach. Birth Detroit was selected by the Institute of Medicaid Innovation (IMI) to participate in a national midwifery learning collaborative. As part of their work with IMI, they’re leading a state-level design team to co-create solutions for Medicaid coverage. This is just one component of Birth Detroit’s multi-faceted approach to counteracting the Black maternal health crisis.

Accessing community care

Birth Detroit will be the first free-standing birth center in the city and it is run by and for Black women. With 5% of birth centers led by women of color, Birth Detroit’s cofounders are part of a small, but growing cadre of Black women reclaiming the tradition of midwifery.

“At Birth Detroit, we’re no longer asking permission to save our own lives. This is a justice response to evidence and data that we know is real, and to what our communities want and deserve,” Welch says.

Birth Detroit’s midwives form deep relationships with families early on, visit homes, look through kitchen cupboards and make nutritional recommendations. They ask about familial or community stressors and talk about ways to mitigate them. They identify and recommend treatment for developing health problems before they become severe complications, and make warm connections with specialist providers as needed. And they stick with a family well into a newborn’s first year to ensure everyone stays healthy.

From a health perspective, the vast majority of birthing people in Detroit could be seen by a midwife.

“Midwives specialize in low-risk births and 80-87% of birthing people are considered low risk. And, we keep people low risk, because we think of the person as a whole being,” explains Nicole White, another Birth Detroit co-founder.

Unfortunately, there are several systemic barriers. While the clinic currently covers prenatal and postpartum care, Birth Detroit is not yet licensed to deliver babies in the state of Michigan. Becoming licensed would allow the center to be recognized as a health care facility that would make it possible for certain Medicaid provisions to begin. Under federal law, state Medicaid plans must cover both professional fees and facilities fees for any licensed midwife who attends birth at a licensed birth center. The facility fee coverage is the key to making birth centers financially feasible.

Further, while hospital births with certified nurse midwives are covered in the state of Michigan, community birth outside of a hospital setting is not, which leaves this option inaccessible to a large number of birthing people.

The work is personal

IMI has state-level design teams in Arizona, California, Kentucky, Michigan and Washington state. Like all of IMI’s state-level design teams, the Michigan team includes representatives of the state Medicaid agency, Medicaid health plans, provider groups and community organizations.

“I’ve observed over the years that each of these different stakeholders is working towards the same outcome. I mean clinicians, community-based organizations, Medicaid health plan providers – everyone involved with Medicaid. I’ve never met anyone who chooses a career working in Medicaid who isn’t mission-driven. They’re in it, because they care about the Medicaid enrollee, family and community as whole,” says IMI’s founder, Jennifer Moore, who has more than 20 years of experience in clinical practice, research and policy.

For Moore, the work is personal. As children, her parents lost their jobs in the auto industry and so she and her three younger sisters received Medicaid, WIC and other safety net benefits. Later in life, Moore witnessed all three of her sisters nearly dying while giving birth.

Nicole White of Birth Detroit is the lead for the Michigan team participating in IMI’s midwifery learning collaborative. She called on long-time colleagues and collaborators, all of whom care about Black women’s health and for whom the work is as deeply personal at is for Moore. White herself became a midwife after learning her great-grandmother had been one.

Her collaborator, Leseliey Welch, became passionate about public health as a pre-med student in 1998 in Durban, South Africa, where she saw babies dying of AIDS every day.

“While babies here in the United States had access to anti-HIV drugs, the babies there did not. What I understood then was health was about more than good doctors, because South Africa had good doctors. I realized health was about whose lives we value,” Welch says.

For Welch, Medicaid coverage for midwifery is about determining whose lives matter.

“We continue to grapple with this hierarchy of human value – race or credentials. So White bodies over Black and Brown bodies, or obstetrics over midwifery. We have to get beyond all that and do what’s best for our families,” she says. “This collaboration is a monumental opportunity for Michigan that I haven’t seen in the history of my public health career. With this assemblage of players at the table and conversation with shared interest, I think there’s so much potential and I hope that we can really use it to make our state better.”

Welch and White’s colleague, Elon Geffrard, brings insight from her tenure as a doula and childbirth educator. She attended her first home birth at age 5, when her brother came into the world. Later, as a community health worker, she became acquainted with a 19-year-old Black woman and mother-to-be who did not have familial support.

“She called me from the hospital and said she’d been in labor for more than a day – and without medication,” Geffrard says.

Geffrard decided to show up at her side for the duration of the birth process to ensure she received appropriate care. She says the work of Medicaid innovation is about changing the perception of what Black birthing people and those covered by Medicaid deserve.

“In spaces where people have that intersecting identity, with lower socioeconomic status, maybe less education – or just having Black and Medicaid associated with your chart – changes how people perceive you and automatically creates moments of disparate treatment, disparate quality of care, assumptions made about people,” she says.

Susan Gough is a registered nurse who sits on the team as a representative of insurance provider, UnitedHealthcare. She says designing new systems requires the ability to look at people in a holistic manner, a capacity she built as a nurse. That is timely work.

“Pregnancy care in the U.S. has not meaningfully changed in decades, despite the poor outcomes we see. There is a need and room for new models that bring a different level of respect, shared decision making and humanity to the process,” Gough says.

White also invited long-time collaborator, Deborah Fisch, vice president of the Friends of Michigan Midwives. Fisch worked with midwives when giving birth to her two children and the experiences changed her life completely.

“I had the good fortune and connections to be aware of midwives and the resources to hire one. My births were empowering. They gave me a whole new relationship with what my body could do and how I could fully inhabit myself,” Fisch says. “The bond you form with your midwives inspires loyalty. I felt I had incurred a debt I needed to pay back.”

So, Fisch pursued a law degree specifically to defend and advocate for midwives.

Fisch says Medicaid coverage for midwifery care will be a marker of our health as a society and echoes the sentiment that all the right decisionmakers need to work on solutions together.

“Two big markers of the general health of any society are its infant and maternal health numbers,” she says. “As a country, our markers are bad – we’re failing parents and children, especially Black mothers and babies. This makes it all the more important to address the problem. Aside from a different model of care, there has to be an understanding of how institutions end up deciding how they’re going to take care of people.”

Comments