In the southern United States, our New Orleans and Mississippi teams recall leaders who left an indelible mark on their communities and paved the way in civil rights, healthcare, entrepreneurship, maternal-child health, education and food systems.

Mississippi

For Rhea Williams-Bishop, director of Mississippi and New Orleans programs, Black history is personal. She draws strength from the legacy of her aunts Winson and Dovie Hudson. The sisters were instrumental in the 1960s securing voting rights, access to health care, housing and childcare and for infrastructural improvements like telephone service and roads for Black residents of Leake County, Mississippi. They also hosted young activists in their home during the 1964 Freedom Summer.

Williams-Bishop also considers Theodore Roosevelt Mason Howard a hero. He was the first chief surgeon of a hospital founded by a fraternal organization in Mound Bayou, Mississippi, a town established by formerly enslaved people after the Civil War. Among Howards’ many contributions was mentorship of famed civil rights heroes Medgar Evers and Fannie Lou Hamer. Howard also offered his scientific mind to the investigation of Emmett Till’s kidnapping and murder, while his home became command central for journalists covering the traumatic event.

Program Officer Jed Oppenheim, says: “I don’t think our work gets done if it were not for Fannie Lou Hamer. She was from Sunflower County, Mississippi, and is known for her voting rights and civil rights work. But she has a trajectory that literally touches all of our work in the South. Before she was known for her civil rights work, she had been medically sterilized by White doctors – like many Black women seeking treatment for unrelated issues – and that led her to become a maternal-child health advocate.”

Hamer also helped establish Head Start programs and Freedom Schools in Mississippi; late in life she started the Freedom Farm Cooperative growing and supplying fresh foods and products for cheap or free to local, mostly low-income residents of the Delta.

“You can’t get three steps in this work in Mississippi without Fannie Lou Hamer,” says Oppenheimer.

Wesley Prater, program officer in Mississippi thinks of “Dr. Robert Smith, a physician who has worked to improve access to care for Black people since the Civil Rights movement and co-founded the first rural federally-qualified health center (FQHC) in Mound Bayou in the Mississippi Delta. His FQHC became a national model and there are now over 1,300 across the United States.”

Learn more about Fannie Lou Hamer through a documentary premiering on PBS on Feb. 22, 2022,, funded in part by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

Prater also recalls living legends, father-daughter duo Bill and Tony Cooley, business owners in Jackson, Mississippi. Among their many enterprises is Systems Electro Coating LLC, a supplier for Nissan and Toyota. Bill Cooley founded his consulting agency in the 1970s and has mentored many people of color as they start their own enterprises.

New Orleans

Ciara Coleman, program manager in New Orleans draws inspiration from Oretha Castle Haley, a civil rights-era leader and founding member of the New Orleans chapter of CORE (Congress of Racial Equality). Her work touched voting rights, employment equity and health equity, with her advocacy leading to a Supreme Court Case that desegregated Charity Hospital.

“The historic OC Haley Boulevard is named after her,” says Coleman. This is fitting as OC Haley Boulevard was once known as Dryades Street, where Haley’s first foray into activism took place with a boycott of Dryades Street businesses. “Her legacy and work tie nicely with economic development and entrepreneurship as OC Haley Boulevard is now a hub for Black-owned business and economic revitalization.”

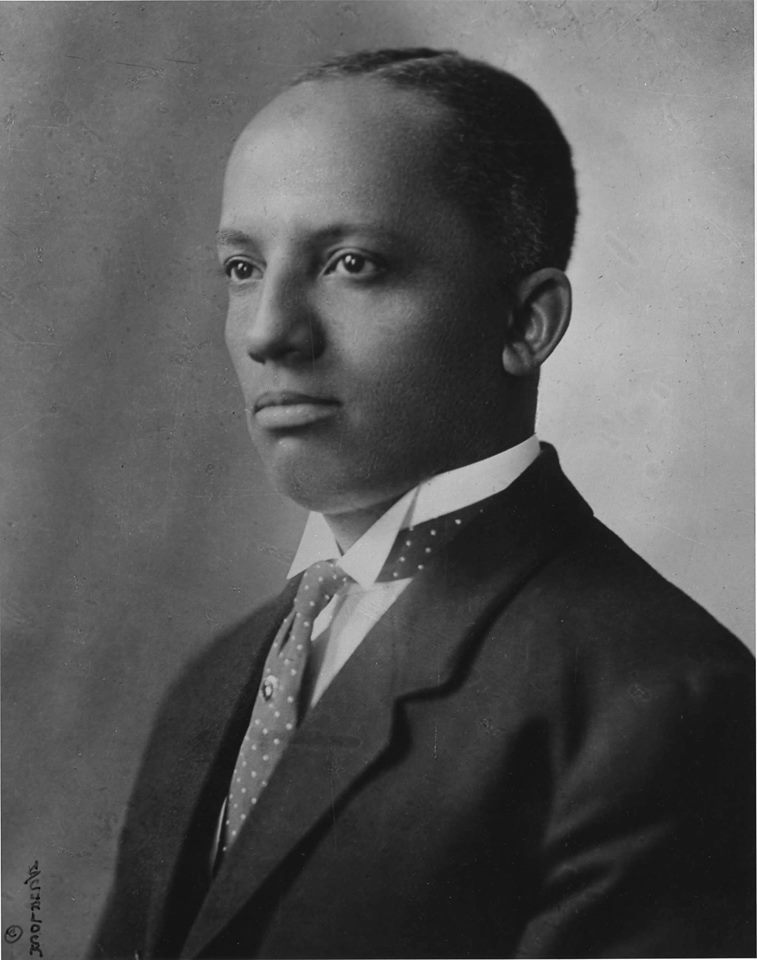

When Senior Program Officer Deirdre Johnson Burel thinks about education systems, she calls to mind the work of Carter G. Woodson, from Canton, Virginia. Woodson is the father of Black History Week, which later became Black History Month.Woodson was largely self-educated early in life, spending most of his childhood contributing to his family’s income through farming and working in coal mines. He entered high school at age 20 and later become the second Black person to earn a PhD from Harvard. In 1915 he founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History and later began publishing the Journal of Negro History, still in circulation today as the Journal of African American History.

Johnson Burel says Woodson’s seminal work, The Miseducation of the Negro “made the case for culturally relevant pedagogy – long before that term was coined in research.”

Johnson Burel also draws great strength from Lisa Delpit, who currently lives in Baton Rouge. “I believe she may be Louisiana’s only MacArthur Genius,” says Johnson Burel. “Her work is foundational to what we today call culturally-relevant education.” In Silenced Dialogue, adds Johnson Burel, Delpit surfaced what often goes unsaid in how race is practiced in education.

Finally, Kathryn Parker, program officer in New Orleans says, we can’t forget the great Leah Chase: “Not only was she the queen of Creole cooking for many years, she provided a safe space for leaders to meet throughout the civil rights movement in New Orleans. Her support of Black artists is unmatched and her own board service on many nonprofits illustrates her generosity.”

Chase’s legacy reminds us that every one of us can make a unique contribution as we actively pursue racial equity – even ensuring those on the frontlines have the calories to keep going with the work.

Comments