“Who is an American?” asked Unmi Song before an audience of two hundred. “For me, when I hear the word American, I picture the Marlboro man.”

Moments later, her sister in story Chanita Jones-Howard confessed to feeling “sick and tired of being sick and tired:”

“That’s been my story. That was my mother’s story. That was her mother’s story. …I’ve done a lot with the burdens on my shoulder. I’m looking forward to doing so much more with them under my feet.”

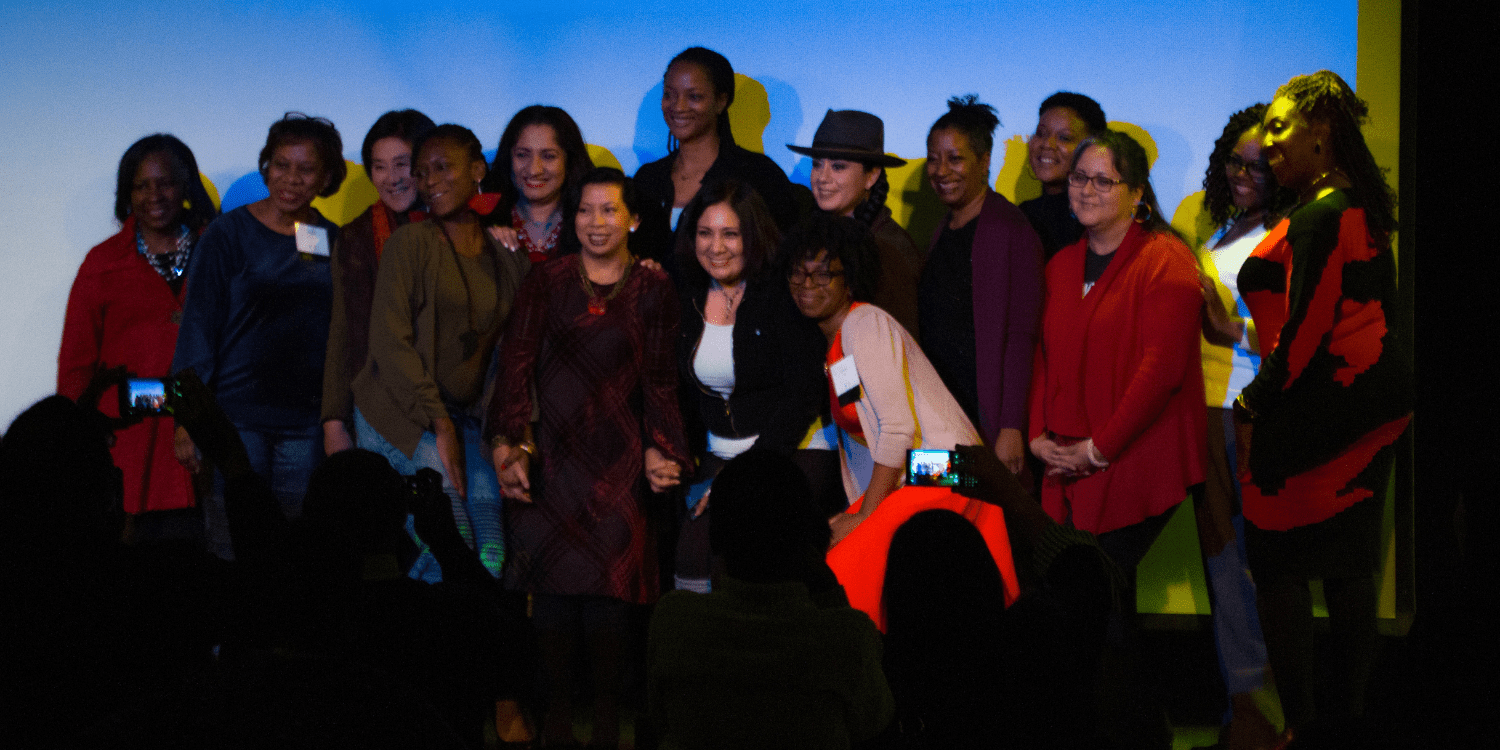

Fifteen women shared memories of racialized experiences with a standing-room-only crowd during Chicago’s National Day of Racial Healing 2019. Stories included:

- Repeatedly fielding questions from strangers who are shocked to learn Native Americans are alive and living in Chicago;

- Marrying one’s lifelong love, while he’s shackled, at Cook County Jail;

- Soul-level conversations with a grandmother whose name was never recorded.

Some might call it brave; Jones-Howard called it relieving.

“Sometimes when you carry these burdens and they become a part of who you are, they can be so heavy. But, the responses I got from the audience let me know that I’m not alone, that other people have experienced these things. It lifted the weight off, because now you’ve heard my story, it means we’re sharing [the burden] together.”

The Chicago Vibe

When left to the evening news, the Chicago story reads as one-dimensional. The truth is, a multitude of stories course through Chicago’s broad avenues and vintage brownstones.

“We make headlines all the time and not for good reason,” admits Jaye Hobart, formerly of the Woods Fund, who co-hosted the event.

The headlines miss the energy one feels in the city.

“The Chicago vibe is complicated, but activated. We are the most segregated city in America. But, we have an incredibly strong history of organizing.

For example, during the Jim Crow era there were black newspapers reporting on racial injustice. We had a contract buyer’s league collectively re-negotiating home-buying policies. And now, we have an alliance for police accountability trying to pass an ordinance for a Citizen’s Oversight Board.

Our organizing roots are just as deep as our Jim Crow roots.”

Sisters in Story: Now that There’s Trust, We Can Get to Work

Preparing for the storytelling event gave the women a special opportunity to bond. They attended performance workshops at the city’s premier Goodman Theater and curated the run-of-show together.

Unmi Song describes the workshops as being almost as powerful as a racial healing circle, a practice often at the core of racial healing efforts.

“It was most interesting to hear the resonance in the room – the parts of our stories that felt relatable. When I went through my story, one of the African American women said it was strange to hear the word American over and over again. ‘We’re never just American, we’re always hyphenated.’ That was something I could relate to.”

Chanita Jones-Howard says storytelling is a uniting force, especially in a large segregated city:

“I can’t think of another reason I would have shared such intimate space with the other women. I call them my storytelling sisters now.”

Jaye Hobart says the workshops had an unanticipated outcome:

“The bond created from those workshops was so strong you could feel it in the room during their performance. And that’s important, because there were two foundation presidents and several community organizers among them. This group can really work together now because they’ve built that trust.”

Unmi Song is the President and CEO of the Lloyd A Fry Foundation. Chanita Jones-Howard is Co-Founder and Executive Director of Recondition Community Cooperative and a veteran Chicago Public Schools teacher. Jaye Hobart is now director of development at Civic Federation.

Comments