When the people most impacted by systems come together to support one another and heal, they often go on to effect powerful change — from the ground up. This grassroots approach is at the heart of the work of Bold Futures, a Las Cruces, New Mexico, nonprofit. The organization’s “touchstone groups” showcase how communities can channel lived experience for good, with powerful impacts for the next generation.

In the summer of 2020, amid nationwide protests for racial justice, a group of Black women leaders across New Mexico found each other.

They lived in different cities and had diverse backgrounds, but they shared an important identity at a challenging time. While New Mexico is a racially and ethnically diverse state, fewer than 3% of New Mexicans identify as Black, according to U.S. Census data. In 2020 especially, many Black leaders in New Mexico — particularly those living in the southern and more rural parts of the state — said the pandemic and the broader community’s response to the killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer exacerbated the isolation they already felt.

While communities like Las Cruces hosted protests and rallies in support of racial justice, Floyd’s killing was polarizing. “It is psychologically challenging to see people that you’ve grown up with, your teachers, the connections that you’ve made throughout your whole life — to see them react in a way that denies your humanity,” said Heather Smith, the group’s facilitator.

To support this need, W.K. Kellogg Foundation grantee Bold Futures, alongside existing and newly recruited Black community members, formed the Black Leader’s Circle (BLC), a support and activism group where members share their lived experiences and channel them into collective action. Since then, BLC has advocated for — and even influenced policy on — racial justice, reproductive rights and other issues important to the state’s Black communities.

The W.K. Kellogg Foundation has supported Bold Futures with general operating grants since 2012.

The need for connection

In the parlance of Bold Futures, BLC is a “touchstone group” — a circle of people who share identities and experiences, or who face similar challenges. Together, they find support and rally to spark change in their communities. BLC is one of six touchstone groups. Other groups include a queer/trans circle, a group of Indigenous birth workers and a group of people impacted by the child welfare system.

Bold Futures doesn’t dictate what issues each group tackles; instead, it facilitates and resources them to take on whatever issues they decide to prioritize, thus centering the lived experiences and expertise of those most impacted. Bold Futures also gives members of BLC scholarships and professional-development opportunities to support their work.

But oftentimes a group’s work begins with healing.

BLC member Davetta Wilson grew up in Albuquerque in the 1960s. At the first daycare center she attended, employees kept her in a closet away from the White children, she said, after parents complained. In school, Wilson was often the only Black student in her classes and was bullied relentlessly, something her teachers often ignored.

“It was miserable,” Wilson said. “If I responded in any normal way, I was the agitator. I was the aggressor. Even now at 61, I’m realizing how much of that is still locked in my brain. I can’t respond to things that someone else could respond to. I can’t be the angry Black woman, or I lose access to spaces.”

For Wilson and other BLC members, having a safe space to share and to work through these traumas has been pivotal. The group has offered opportunities for connection, creativity and healing. Wilson, who is a potter, said she has channeled her emotions into her creations, some of which were featured several years ago at a BLC-sponsored art show. And now, Wilson is passing her activist spirit on to the next generation. Her daughter, Orchid, is also a BLC member.

“I have wonderful friends who are White, Hispanic, Asian, South Asian, and so on,” said Wilson. “They’re lovely people, but it is not the same. There are things people cannot understand unless they’ve had this experience.”

Another BLC member, Queva Hubbard, credits BLC with encouraging her to quit a terrible job and return to school. Hubbard is a social worker who grew up in Clovis, New Mexico, and now lives in Albuquerque with her daughters.

“I always just felt like I had to be strong,” Hubbard said. “I had to put on this mask when I walked out the door. I had to be OK to make other people feel OK. The sacrifices I’ve made and the things I’ve accomplished have all been because I’ve had support from the BLC — other women who were like, ‘It’s OK to feel like this. It’s OK to cry. It’s OK to not know what to do.”

In each touchstone group, the tight-knit circles that form are better able to engage with their broader communities because they have a place to come back to — to vent, process and plan.

From solidarity to change

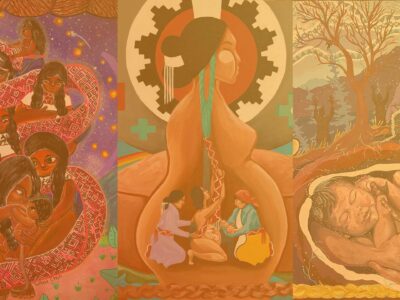

Since its formation, the members of BLC have participated in guided healings, led book studies, drafted a resource guide for Black birth workers and created a coloring book for Black children. They’ve hosted community trainings, art shows and advocacy events. And they continue to shape public policy, meeting regularly with legislators, submitting public comments and writing op-eds to elevate Black perspectives in policymaking.

“We tell our story,” Hubbard said. “Lawmakers are having these discussions in these rooms with doors closed, but we’re going into those rooms, and we’re reminding them, ‘You all are sitting at the table making decisions for us, but we’re here telling you that those decisions are not working.’”

The group advocated for Senate Bill 13, the Reproductive and Gender-Affirming Health Care Protection Act, passed in 2023, which safeguards patients and providers of abortion and gender-affirming care in New Mexico from out-of-state legal actions. BLC has also worked to expand access to contraception, especially in rural areas where pharmacies and reproductive health services are limited.

BLC members helped advocate for New Mexico’s version of the CROWN Act, which bans discrimination based on hair texture and style. Gov. Michelle Lujan-Grisham signed the bill into law in 2021.

“We’ve all seen the stories of African American students having their hair cut at school by a teacher or a coach because their hair looks ‘thuggish,’ or similar nonsense, just growing the way it grows out of their head,” Wilson said.

BLC members also supported “Ban the Box” legislation, which removes conviction and arrest history questions from job applications, giving applicants with criminal records — who are disproportionately Black men — a fairer chance at employment.

Belonging and power

On a fall day, a few members of the BLC gathered in an Albuquerque park to create “Hug Hoodies.” They painted their arms and hands with brightly colored fabric paint and hugged each other — creating a tangible reminder that they are always being held by each other.

“Because of my past and what I have been through with trauma and people touching me, for another person to hug me with love and empathy, it was like something broke in me,” said Hubbard. “And Davetta — she’s like the mama of the group — when she hugged me, a weight lifted.”

Through these efforts, members have also grown into leaders in their own right. Several have taken on new leadership roles within Bold Futures and other advocacy spaces across the state. Smith herself, who joined BLC before working for Bold Futures, now serves as the organization’s deputy director.

Five years after their first Zoom call, the Black Leader’s Circle has become far more than a support group — it’s a movement. Through their advocacy, art and collective healing, the women of BLC have helped shape legislation, expanded access to reproductive care and created spaces where Black New Mexicans can see themselves reflected and respected.

What began as a small circle has grown into a statewide network of belonging and power. And their work continues — not just in policy rooms or public events, but in every space where a Black leader in New Mexico feels seen, supported and ready to lead.

Comments