The W.K. Kellogg Foundation’s Black affinity group, MIZIZI, honors the centuries-long tradition of community giving and mutual aid within Black communities. Their stories highlight how, for many of our staff members, philanthropy is a commitment and personal practice that is rooted in Black history, family tradition and vision for a more prosperous future.

Affinity groups are a big part of WKKF’s racial equity and racial healing journey. They promote and honor the wisdom, experiences and histories of the foundation’s diverse workforce, and offer opportunities for peer support and learning that help us to be creative, innovative and equity focused in all that we do.

Philanthropy for Black futures

with Yazeed Moore

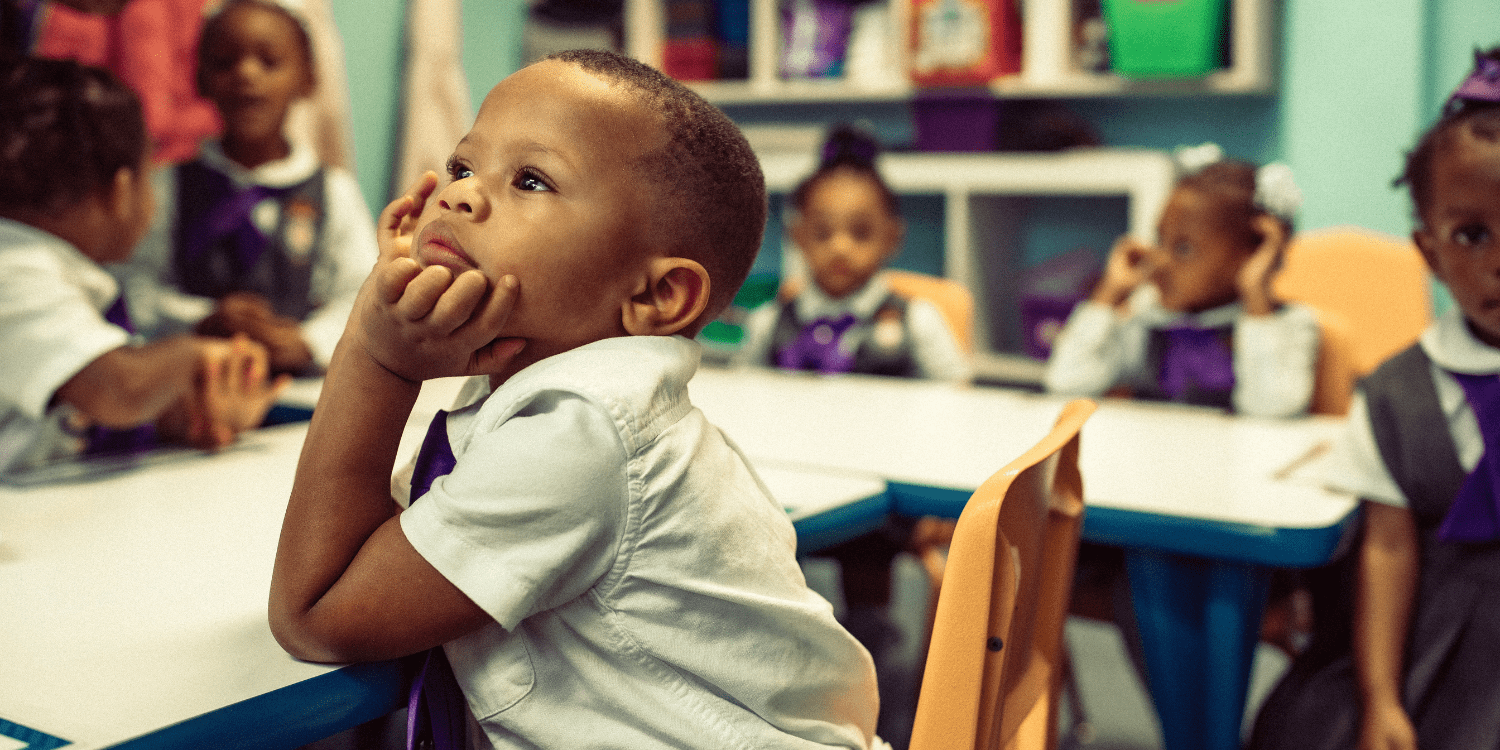

Yazeed Moore is a senior program officer on WKKF’s Michigan team, primarily focused on supporting early childhood education across the state. His career in philanthropy stretches across more than two decades, rooted in a deep commitment to children, especially children of color, and promoting their best start.

Q: If you meet someone out in the community for the first time, they might ask “Who are your people?” How would you respond to that?

A: My people are those I come across who are dedicated to improving opportunities for people that look like me and come from circumstances like my own. Those who are helping people tap into the deepest depths of their potential to have the life they fully deserve. This is especially important when you talk about Black people here in the U.S., who haven’t necessarily had the access to opportunity because of historic injustice and generational trauma.

As we envision a path forward, I go back to this question, “Are there Black people in the future?” Octavia Butler, the American author and futurist, compelled us to think about Black people, Black excellence and Black brilliance in the future. Black people’s pain and struggles have been so prevalent. I often wonder, “How do we learn and move forward to begin to narrate a future where Black people are living in their fullest and grandest potential?” And so, when I think about who my people are, it’s those who are asking and answering these questions.

Q: You're from Gary, Indiana. How do you carry your hometown with you?

A: Everything I grew up in and experienced in Gary, fuels what I do and who I am today. Gary is a predominantly Black, rust-belt town. I grew up in the era when the steel mills were fully functioning, I had uncles and grandfathers who worked in those mills and provided for their families. Gary is not that same city anymore. Things were changing even as I was growing up.

It later became a city known for concentrated poverty and chronic violence, stemming from its economic conditions. But I didn’t see Gary as that. I saw it as the place I grew up and the place that helped me see why the world wasn’t right. Why did a neighboring community that was only 15 minutes away, a mostly White suburb, have all the things that I didn’t have in my own neighborhood? Those experiences shaped my worldview, it became the grounding of the social work, social justice and fairness work that I do. I told myself, “I have to find a way for kids who grew up like me, in a town like Gary, to actually dream and aspire to do something more.”

I grew up in a small Section 8 apartment. There were reasons why I grew up in that environment and it wasn’t because my mother didn’t work hard.

“There were structural things that allowed a young Black boy like me to be in that space and time, no fault of my mother. So, how do you begin to think about dismantling those systems and structures that didn’t allow my mother to see her full economic potential.”

Those experiences have evolved into the change work I do every day: hard pressed on making life much better and much grander for Black folks to see themselves, not only in the present, but also in the future and doing very well.

Q: How did you arrive to the field of philanthropy?

A: My mother and my family have always been philanthropic in nature, even if we didn’t call it philanthropy. It was our responsibility to make sure that we did something to help others along. That was my first introduction to philanthropy: Black folks investing and helping each other.

I was introduced to the field of philanthropy early in my professional career, and it’s become my life’s work. For me, it’s about being a steward of resources. It’s about providing resources that create opportunities for the betterment of my community. Philanthropy can be a gap filler, a connector and convener to bring systems together to think about the opportunities that are available in communities. I’m a firm believer that we should live in a society that puts people’s well-being and aspirations at the forefront to ensure that they are able to find purpose in living their best lives economically, academically, educationally and beyond.

Q: In many ways, you are now in the position to support a version of your younger self. How does it feel to be able to do this work in support of children who grew up in environments like yours?

A: It is one of my greatest joys to be able to do this work in partnership with people.

“This all started by the love and the commitment that my mother showed me; she’s my greatest hero and the reason I am so passionate about early care and early childhood education.”

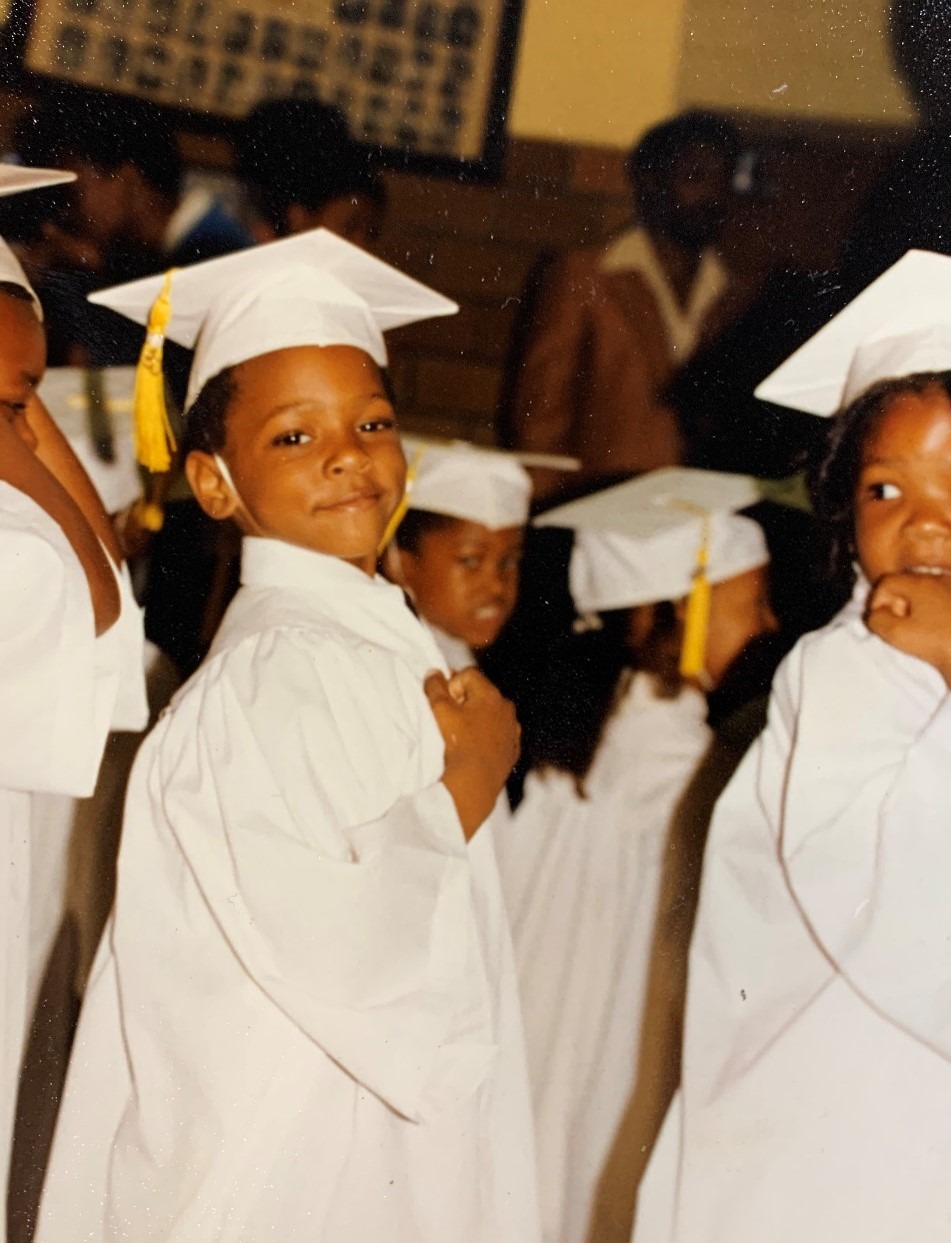

When I was four years old, my mother was looking for an early care place to send me. She thought I needed something more than she could provide. So, she enrolled me in the Elka Child Education Center that got its start through War on Poverty funding in 1968. That opportunity changed the trajectory of my life. And I’m glad to know that the center still stands today.

I carry this experience with me, knowing that there are Black parents out there who may not have had the best go at life because of historical trauma and racism (and all these other isms) that sometimes sidetracks them from being able to advance and achieve their aspirations for their children and families. This lived experience shapes how I approach early care and early childhood work across the state of Michigan, in Grand Rapids, Detroit, Battle Creek, Flint and elsewhere.

Q: You recently received the Dr. Gerald K. Smith Award for Philanthropy from the Council of Michigan Foundation. What did that mean for you?

I can humbly say that I’ve never done this work for praise or adulation; I’ve done the work because it needed to be done. I’ve done this work to make sure that Black people and kids of color can see themselves in ways they’d never imagine, even if their life circumstances haven’t been the best. My mother was top of mind in receiving this award because those lessons came from her. It was the greatest honor that I could have had.

Q: You’ve worked in the field of philanthropy for more than 20 years. What's something you’ve learned during your career that shapes the approach you take to grantmaking?

A: I got a lesson early on in this work by a mentor who said, “Hey, young man, this work is about people. Keep that center and focused as you move along this career.” People always know best what they need for their communities. So, I see my role as a partner, working with people who know best and helping them articulate what the solutions are to their challenges. I’ve tried to hold on to that and making that be a part of me every day.

“The best compliment someone could pay you working in this field is to view you as a practitioner with access to resources, as someone who is in the trenches with them.”

Comments