This February, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation’s Black affinity group, Mizizi, honors the centuries-long tradition of community giving and mutual aid within Black communities. Their stories highlight how, for many of our staff members, philanthropy is a commitment and personal practice that extends well beyond the workday and is rooted in both Black history and family tradition. Today, WKKF supports locally driven philanthropy by communities of color through Catalyzing Community Giving.

Affinity groups are a big part of WKKF’s racial equity journey. They promote and honor the wisdom, experience and histories of people of color, foster community participation and offer opportunities for advancement through peer mentoring.

My giving is a family affair

with Dr. Marijata Colley Daniel-Echols

Marijata Daniel-Echols is a program officer on WKKF’s Michigan team, who primarily focuses on health equity during the work week. In her personal life, her family gives time, talent and treasure to support young children, families and their communities in Michigan, Maryland and Pennsylvania.

How are you involved in community-based giving? Are you part of a giving circle or another type of initiative in your local community?

Every job I have ever had has been about serving in ways that help people of color thrive and chip away at systemic racism. Other forms of service include being on boards and providing mentorship to Black professionals who are earlier in their careers than I am.

Are there elders in your family or mentors who demonstrated the value of giving early in your life?

I was raised with the expectation that I would do things with excellence and that the things I do would be for the betterment of the race. I know that sounds very old school NAACP – but that’s the generation my grandparents represent. My parents represent the Black power part of the 60s civil rights movement. My family is filled with teachers, lawyers, doctors, nurses, ministers, deacons/deaconesses and other professions that at their essence, are all areas of work in which you are serving and helping others.

What inspires you from the rich history of community-based giving and mutual aid within Black communities?

My grandparents all came from humble beginnings in Virginia and Alabama and went on to become first generation college graduates and/or community leaders. They gave their time, talent and treasure to serve their communities and fight for racial equality. My parents continued in this same spirit in the education space (my mother in early childhood and my father in higher education).

Who do you give alongside? What brought this group together?

My giving is a family affair. When my children were young, we made a point of passing on the expectations of service and gave them experiences doing volunteer work. They have seen their grandparents give to support Black students’ ability to afford higher education (e.g. endowed scholarships to cover books and tuition) and scholarships to help professionals of color afford conference attendance and other professional development opportunities – all of these named respectfully for their grandparents and great grandparents to recognize their legacies of giving.

There is a difference between charity and philanthropy, and we try to stay focused on philanthropy. When I think about charity, I think about meeting people’s immediate needs. It is important work and serves a purpose when what people need is immediate help. Philanthropy is an opportunity to do that and to think strategically about the longer term and how to address systemic issues.

An example I have used before is that a food bank can (and should) give away food all day, every day to hungry families. At the same time, we should be working to understand why those families are hungry and what can we do to address the underlying cause of their hunger. Charity can, in theory, go on forever. Philanthropy at some point can end, because through strategic investments in community-led work, we can fundamentally change the context for families, such that no one is hungry and no one needs to give away boxes of food.

I was raised with the expectation that I would do things with excellence and that the things I do would be for the betterment of the race.

Marijata Daniel-Echols

Working for a major foundation, you could easily say you “gave at the office.” Why is it important to you personally for your giving to extend beyond your professional life?

As a result of the way I was raised, every job I have ever had has been about serving in ways that help people of color thrive and chip away at systemic racism.

My day-to-day WKKF is work is a part of my service to community. In addition to the administration of grants, I contribute my time and talent by working in thought partnership with our grantees and participating in regional, state, and national committees focused health/race equity (e.g., Michigan’s state Coronavirus Taskforce on Racial Disparities). I choose to spend additional time in nonprofit board service as well as by mentoring, when asked, Black professionals who are early in their careers because it is a way to make a difference outside of the confines of a job. Mitigating the harm of systemic racism and working to eliminate it requires multiple strategies – so the privilege to work in philanthropy and how I spend my personal time allows me to leverage my skills and access to resources in ways that matter.

Philanthropy means loving people

Jonathan Pulley is a program specialist on WKKF’s racial equity and community engagement team. He lives in Kalamazoo, Mich., where he was born and raised and now gives back through service.

How are you involved in community-based giving? Are you part of a giving circle or another type of initiative in your local community?

One thing that I appreciate about community-based giving is that it requires more than just money to help resolve some of the hardest issues. I not only give to local organizations that look to reduce poverty in Kalamazoo County, Mich. but also bring my lived experience, professional networks and cultural understanding to these organizations.

The origin of the word philanthropy is rooted in the Greek language and means “Man-Loving.”. To love humans requires a layered approach and I understand that communities need more than just dollars.

What community is served by your giving efforts?

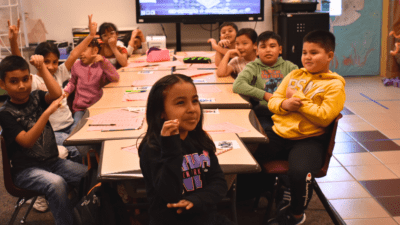

A lot of my passion is based on giving back to a community that gave so much to me. I volunteer with the City of Kalamazoo’s Shared Prosperity program and other nonprofits to help reduce poverty by ensuring parents are able to have a career pathway to greater income and that young children have support systems (schools, community organizations etc.) that promote a two-generation (families and children) approach for success.

Are there elders in your family or mentors who demonstrated the value of giving early in your life?

I appreciate what my parents instilled in me at an early age, showing me that we always have something to give. Many of my Saturdays as a kid were at community organizations, volunteering or helping those in need. This kept me humble growing up and showed me a reality about how to be a part of change within a community. As a parent of three, I want my children to know and be in tune with communities that look like them and for them to be passionate about community-based work.

As a parent of three, I want my children to know and be in tune with communities that look like them and for them to be passionate about community-based work.

Jonathan Pulley

What inspires you from the rich history of community-based giving and mutual aid within Black communities?

I believe it has always been around and I feel proud to give back in a way that fits my convictions and life.

When I think about community-based giving, I think about the African Proverb: “It takes a village to raise a child.” When we center our lives around the betterment of our children, that makes it better for the sum of the group. It gives me joy knowing that I contribute to a larger purpose and feel connected to purpose in the process.

Who do you give alongside?

I give with a combination of family, friends and my local church. Some of the best ways I’ve learned to contribute, is to give to organizations that already have some momentum towards issues I’m working on. In my local church, I have been able to see issues related to poverty, equal access and opportunity to education be built into the benevolence fund.

Working for a major foundation, you could easily say you “gave at the office.” Why is it important to you personally for your giving to extend beyond your professional life?

What’s meaningful to me is knowing that I get to be a part of the solution from a more hands-on perspective. I also believe in the core beliefs of our founder (W.K. Kellogg) who said that “… communities have the inherent capacity to solve their own problems.” I am leaning into the foundation’s beliefs when I choose to be a philanthropist outside of my day-to-day work.

I know now that we need to be close to the work. But you don’t always have to be front and center or look to get recognition. It’s important to advance a community through spending time with local residents and leaders to get an understanding of the real needs of the community. Depending on the stage you are at in life, you can be intentional about the ways in which you give, but all methods of contribution are needed.

More info about community giving

Throughout the centuries, community giving and mutual aid within Black communities often came with great personal risk. Here are a few highlights from the hundreds of thousands of stories that could be shared.

Scholar W.E.B. DuBois began his 1907 study on mutual aid by recounting the burial and beneficial societies developed by enslaved people in nearly every Virginia city. Since it was illegal for enslaved Black people to congregate, each society selected a secretary and members visited them in ones and twos to pay dues.

In 1787, founders of the African Methodist Church, Absalom Jones and Richard Allen established the Free African Society in Pennsylvania. Members paid one silver shilling of Pennsylvania currency each month, and three shillings a month were disbursed to widows. The society also secured apprenticeships for children of the deceased.

DuBois describes the Underground Railroad of the 1830s-1850s as a vast network of “conscious cooperation and organization,” involving financial support, shelter and security as people escaped enslavement. Many liberated people embarked on what he called “heroic errands of mercy and deliverance,” risking arrest and re-enslavement to in turn free others.

More than a century later, Black sharecropping women in Alabama established the Freedom Quilting Bee. They sold enough quilts to purchase 23 acres of land, where they built a quilting factory and offered shelter to sharecroppers who had been fired and evicted after registering to vote.

Mutual aid continues, now a hallmark of the COVID-19 era in communities across the United States, crossing boundaries of race, origin and language.

Comments