Programming team members in our hometown of Battle Creek, Mich., and nearby priority city, Grand Rapids, Mich., recall Black leaders of the past who paved the way in civil rights, economic development and racial equity and changemakers of the present who are shaping systems to better support the ability of children and families to thrive.

Truth

For Program Officer Alana White, “It’s impossible to talk about Battle Creek and not talk about Sojourner Truth’s legacy.”

Born in upstate New York around 1790, abolitionist Sojourner Truth fought her own liberation battle, convincing her master to free her before New York’s emancipation laws took effect in 1827. In 1843, she changed her name from Isabella to Sojourner Truth, as she traveled to tell people the truth about slavery.

“Sojourner Truth’s legacy reminds us that anyone can make a difference in our communities,” says White. “She was born a slave and was considered illiterate – and yet she won lawsuits, advocated for economic justice and secured housing and jobs for Black people.”

Truth moved to Battle Creek in 1857 and continued focusing on campaigns related to emancipation during her final 25 years. After her grandson enlisted in the Union Army in 1863, she went door-to-door through town collecting supplies and donations for Michigan’s Black Regiment and frequently visited Black soldiers near Detroit. Working with the National Freedmen’s Relief Association, Truth found housing for approximately one hundred newly freedmen, many in Battle Creek, and helped place more than 3,500 freedmen in paid jobs.

“Her impact was exponential,” says White.

Economic justice

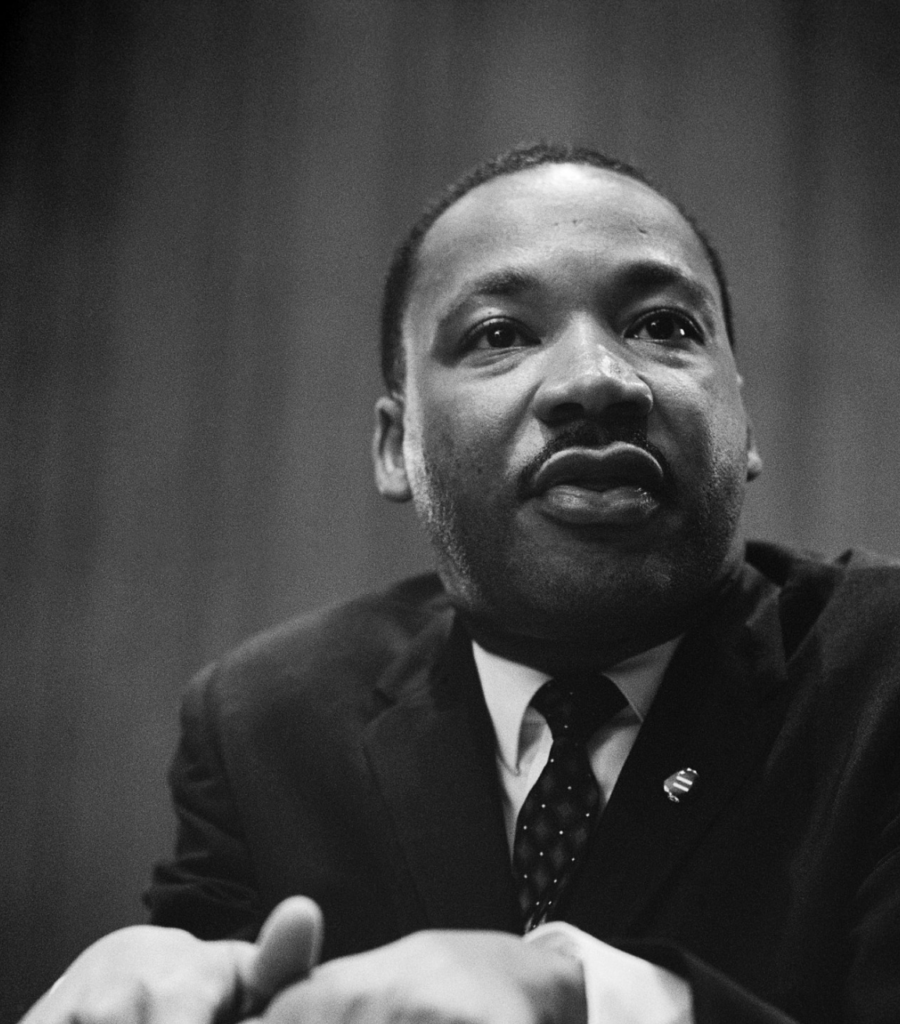

"WKKF carries on Dr. King’s work through our employment equity strategies."

Alana White

The legacy of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Poor People’s Campaign also inspires White’s work in Battle Creek. “Dr. King and civil rights leaders organized the campaign to advocate for economic justice for Black people as well as other racial and ethnic groups,” notes White. “Dr. King was assassinated before the march on the Washington mall – but the march went on. The Poor People’s campaign didn’t reach its aim of adding an economic bill of rights to the U.S. Constitution, but the work continued. Today, WKKF carries on Dr. King’s work through our employment equity strategies.”

Designing equitable systems

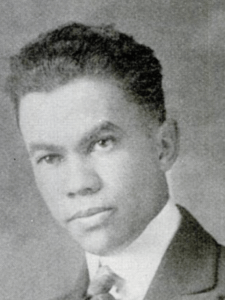

In childhood, White wanted to be an architect and developed a fascination with Paul Revere Williams (1894-1980). Despite teachers telling him he wouldn’t succeed, Williams opened his own architecture practice in 1923. He became the first Black person to join the American Institute of Architects and went on to design the homes of Lucille Ball and Frank Sinatra.

"Inequitable systems don’t change themselves. Systems were created by people and as people we need to change ourselves in order to change systems. Through our community partnerships in Battle Creek, I have the opportunity to design new and equitable systems.”

Alana White

“Early on, Williams learned to draw upside down so clients wouldn’t feel uncomfortable sitting next to him. He was hired to design homes that Black people couldn’t own – and still used his talents to benefit the Black community. It’s legacies like these that I carry with me. While I didn’t become a traditional architect,” says White, “I do consider myself an architect of community systems. Inequitable systems don’t change themselves. Systems were created by people and as people we need to change ourselves in order to change systems. Through our community partnerships in Battle Creek, I have the opportunity to design new and equitable systems.”

Picking up the baton

“Robert Busby immediately comes to mind when I think about entrepreneurship and community economic development,” says Jamie Schriner, a program officer on WKKF’s Battle Creek team. “He helped to recreate the community where I purchased my first and current home in Lansing, Mich., and where I started my career in community economic development.”

A retired General Motors worker, Busby catalyzed the transformation of Old Town in Lansing, Mich., from an abandoned neighborhood to a thriving small business and arts district. He slowly purchased properties and turned them into live/work and commercial spaces, while attracting musicians like Wynton Marsalis and Bela Fleck to perform locally.

“Busby inspired people in the community to believe that any problem could be solved with elbow grease and creativity."

Jamie Schriner

Busby tragically lost his life in 2007.

“After his death,” says Schriner, “people came out of the woodwork to share their stories about how Robert hosted their first art show or purchased their first piece, always inspiring them to do more.”

Fifteen years after his death, Busby is still affectionately known as the Mayor of Old Town.

Learning from community leaders today

In 2007, WKKF’s board of trustees committed the foundation to becoming an effective anti-racist organization, activating collective and individual learning journeys for staff. As President & CEO, La June Montgomery Tabron often points out, “We’re striving to practice and pursue the challenges we’re asking others to undertake.”

Leslee Rohs, a program manager in Grand Rapids, says “There are many Black leaders, thinkers and truth-tellers that help me in my journey to learn (and unlearn) the whole of our history.”

Rohs draws inspiration from contemporary Michigan-based leader and New York Times bestselling author, Austin Channing Brown. In 2021, Brown was keynote during a learning series hosted by West Michigan Center for Arts + Technology, a WKKF grantee in Grand Rapids.

"It is the many leaders and doers we have the privilege of working with who shape and inspire me and our investments the most."

Leslee Rohs

“Her brilliance from that day has stuck with me,” says Rohs, “so much so that I have posted her words at my desk. Austin said:

- We must build community outside the trappings of privilege.

- The more privilege you have, the more risk you can take to use your voice.

- Only by telling the truth about how we got here, can we find another way.”

Rohs continues. “I try to keep these truths at the forefront of my mind in daily decision-making about how to show up in community and as part of a place-based grantmaking team.”

Like many WKKF team members, Rohs is inspired on a daily basis by “the present day Black and Brown leaders on the ground in the communities we serve – providers, organizers and community members working to change systems, policies, hearts and minds to advance racial equity and build power with and for those who have been continuously pushed into the margins. It is the many leaders and doers we have the privilege of working with who shape and inspire me and our investments the most.”

Comments