This post is also available in: Español (Spanish) Kreyòl (Haitian Creole)

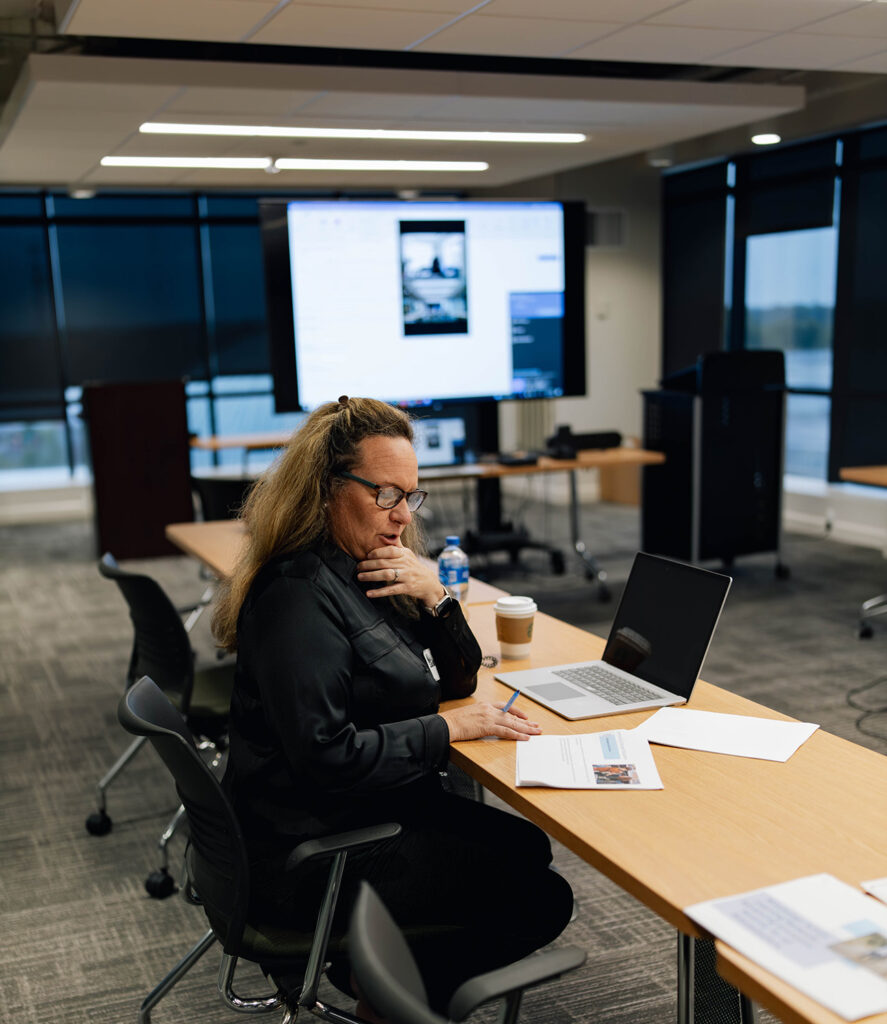

Every six weeks, organizational leaders from the public and private sector gather to discuss better ways to serve the people of Mississippi.

The peer group, called Mississippi Action Learning Network (MALN), consists of about 15 leaders from different statewide agencies. MALN was launched to offer a space for its members to meet and discuss — outside of times of crisis – ways for agencies to share resources and collaborate for the betterment of Mississippi families.

“This is a great group of leaders, and there have been a lot of great ideas that they have been sharing,” said Alex Figueroa, assistant director of learning and development for the American Public Human Services Association (APHSA), who facilitates the invitation-only meetings. “It really kind of provided a platform for them to be in the same room together, build collaboration and really understand the overall impact they are having and how it weaves in all the overall work happening in Mississippi.”

APHSA, which received W.K. Kellogg Foundation (WKKF) support through the foundation’s social impact bond, is a bipartisan membership association that supports leaders from state, county and city human services agencies to advance the well-being of individuals, families and communities nationwide.

At the heart of each MALN meeting is a collective effort to support Mississippians and increase family economic mobility through generative leadership, innovative programming, customer-centered experiences and community-focused education. As a pilot state to advance family economic mobility, the state agency peer group seeks to tackle issues directly impacting Mississippians, with participating members focusing on workforce development, talent acquisition and growth, and transitioning to a more equitable pay scale.

MALN consists of representatives from Accelerate Mississippi; Child Protective Services; Children’s Foundation of Mississippi; Community College Board; Department of Health; Department of Human Services; Department of Mental Health; Department of Rehabilitation Services; and the Mississippi Division of Medicaid.

“Bottom line, we all serve the same clients – the population of (Mississippi),” an anonymous MALN participant stated in a March 2023 midpoint evaluation report. “We’re serving lower income or those on or below the poverty threshold. (The) opportunity to work together with outside ideas is what’s driven us to (join MALN).”

Repairing trust

APHSA originally set out to help repair the public’s trust in the Mississippi Department of Human Services (MDHS) following the state’s welfare fund scandal, where federal funds aimed at assisting low-income families in the state were mishandled by the former MDHS executive director and other former public and nonprofit leaders.

Jennifer Kerr, director of organizational effectiveness (OE) for APHSA, said the first order of business was renewing the public’s trust and shifting the narrative about MDHS.

“Our original ask as part of the OE team was to come in and help support the rebuilding of the culture between DHS and its staff, DHS and the community and the new leadership team within DHS,” Kerr said. “We recognized that we needed to start this journey by supporting staff prior to advancing the work of Mississippians in general – our larger goal.”

Underlining the urgency for improving the well-being of staff, Mississippi annually ranks near the bottom in the nation in a number of health categories. In the United Health Foundation’s 2022 America’s Health Rankings, an annual report that evaluates a comprehensive set of health, environmental and Socioeconomic data, Mississippi was ranked No. 49.

“We can’t expect great outcomes for all Mississippians without the leadership and staff to support and drive that work,” Kerr continued. “That willingness to step back and support staff, and recognition of that importance is key for us as well.”

The playbook

MALN created a playbook for its work across four priority areas: generative leadership, program innovation, customer experience, and community-centered education. Through this vision, it aims for public-private stakeholders (public human services and workforce agencies, intermediaries, businesses, nonprofits, philanthropy, families, and federal partners) to be aligned across systems, fostering equitable systems change through advancing family-centered economic approaches in Mississippi. To date, some of the outcomes and efforts across the four priority areas include:

- Generative Leadership:

- State agency leaders developed staff career and pay ladders, which received approval from its personnel board

- State agency leaders shared staff career and pay ladders with each other and with state peers

- Early Childhood Asset Map was completed

- Potential funding resources and state/federal match dollars were identified and aligned throughout state agencies, community-based agencies and identified partners/stakeholders

- Strategic financing efforts were incorporated throughout the procurement process, including the exploration and origination of funding sources, application development and award implementation

- Agreement to share data across health and human service agencies

- Innovative Programming:

- DHS child care division hosted town halls for information sharing

- Parent coalitions created across the state increasing the voice of lived experiences through a parent navigator model

- Department of Health hosted listening sessions with communities with an approach of “how can we make the suggestion work?”

- DHS Economic Assistance division worked with service participants at the local offices through the community navigator pilot

- Customer-Centered Experience:

- Explored the development of a resource center unique to each county for individuals and families to access multiple services and programs at one location, modeling from Fayette County

- Explored a telehealth model and application for service delivery incorporating the broadband infrastructure bill

- Assessed each community’s service and program area strengths, needs and barriers to participation through feedback and listening sessions with service participants across multiple domains

- Staff committed to providing each customer with a unique and positive experience when participating in health and human services programs throughout the state

- Community-Focused Education:

- Communities educated about the services and programs available throughout the health and human services system

- Explored statewide cross-sector use of the single point of entry hub, sharing information about qualified programs throughout the state

Regional and national learning communities

MALN is part of APHSA’s Advancing Family Economic Mobility Initiative. Through the initiative, a microsite is in development which will publish and share knowledge and artifacts that come out of its learning communities, including the work in Mississippi.

Mary Goble, senior project associate for APHSA, said the coordination of learning communities at the statewide level is an approach that would benefit families nationwide.

“One thing we’re finding with the Advancing Family Economic Mobility Initiative in general, is that the challenges and successes we’re seeing in Mississippi are everywhere. Things like alignment between departments, things like leadership development, recruitment and retention.

These are challenges nationwide and these are challenges that are being echoed and reflected in our national and regional learning communities. In a lot of ways, Mississippi is a case study in what it means for all of these systems to come together to create a consolidated goal and move forward in an effective way.”Mary Goble, senior project associate for APHSA

Creating pathways to a more prosperous future requires a family-centered approach

by Paula Collins-Sammons

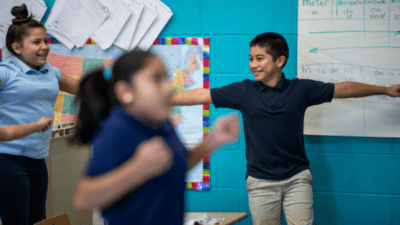

If we want children to thrive, we must not only invest in their quality early education, but we must also invest in the economic mobility of their parents and advance whole family solutions. Given parents and children don’t exist in silos, neither can our solutions.

Unfortunately, too many children in Mississippi are in poverty. In fact, the state has the highest child poverty rate in the nation at nearly 28%. And when children are in poverty, it means their parents are in poverty. In fact, nearly half of Mississippi’s single moms are in poverty, with about 56% of babies in the state born to unwed mothers.

Unfortunately, many of the programs, policies and systems meant to serve families aren’t coordinated, don’t include family voice, and either only focus on the child or the parent – not both. As a result, these solutions fall short and often don’t meet the needs of families. This misalignment can create barriers and additional challenges and make it hard for families to make ends meet, much less move ahead.

This was never more evident than during the pandemic, when schools and childcare centers closed or went out of business, causing children to be at home and impacting parents’ ability to work.

As an example of these everyday challenges, childcare subsidies for low-income families often take three months or more to process. We hear stories from parents who lost the opportunity to start a job or training program because they had no childcare.

Parents also encounter something known as the cliff effect when it comes to childcare subsidies or other supports. They first qualify for the subsidy because of their low income, but once they move up the economic ladder even a little bit, they hit the income cap and lose the subsidy completely, leaving them worse off than before.

There are other barriers as well, such as complicated application processes where families have to go to multiple different agencies to apply for supports, even though the agencies all ask for the same information. For our families, this requires taking considerable time off work and securing transportation.

Recognizing the need to address these unaligned systems that are supposed to serve families in Mississippi and nationally, the American Public Human Services Association (APHSA), in partnership with the Administration for Children and Families (AFC), launched the Advancing Family Economic Mobility (AFEM) initiative in 2021 through a $3.1 million grant by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, building off earlier work in New England.

The Mississippi Action Learning Network (MALN), which is part of that initiative in Mississippi, began meeting as a larger group in September 2022 to center whole families and address the silos, barriers, and misalignment of policy, systems, and practice in Mississippi and also leverage opportunities that advance family economic mobility.

The cohort consists of leaders from state agencies and other stakeholders who regularly come together to establish a sustained vision for family economic mobility. Aligning all of these leaders across all these state agencies has not happened in this way before. Many of these leaders have never met. This means that major state agency heads are sharing information in real time so they can fix and address problems and co-create solutions together, versus only seeing their part of the issue.

Over the past 12 months, the peer group has held eight in-person meetings, reviewing and identifying the highest priorities and focusing on four key areas: generative leadership; program innovation; customer experience; and community-centered education.

One win we celebrated was removing a child support enforcement requirement (enacted 2004) in order to receive childcare assistance. Mississippi was one of only 13 states to force custodial parents to sue noncustodial parents to qualify for childcare assistance. This was one of the biggest barriers to parents working or attending job training programs. The state early childhood advisory council (SECAC), working with Accelerate MS, Mississippi Low Income Childcare Initiative, and partnering with the state Department of Human Services, removed the requirement in May 2023, which has resulted in thousands more parents getting child care subsidies and being able to enter or advance in the workforce.

This systems alignment work is not unique to Mississippi and is needed everywhere, but must be family-centered. If we are to realize our full economic potential and well-being as a state, we need to shift our mental models and see workers as parents, parents as teachers, and children as our future workforce, and meet whole families where they dream.

Comments