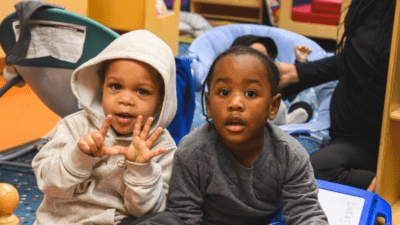

In Kent County, there is a notable gap in early childhood education services. A recent analysis conducted by IFF, a grantee partner of the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, revealed a pressing need for more than 20,000 child care spots to meet the local demand.

This data analysis is an expansion to the findings of a 2018 needs assessment that examined the state of early childhood education services for children in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

By broadening the study’s scope to encompass all of Kent County, local stakeholders can more effectively address the comprehensive challenges hindering children aged five and under in the region, who have not yet reached kindergarten eligibility, from accessing vital early learning resources crucial to their development.

Since the 2018 report, child care spots in Grand Rapids have increased by more than 28 percent, but the 2023 report continues to reveal that on a regular basis parents are struggling to find affordable care for their young children near where they work and live.

Based on the number of slots available, less than 40% of children in the area can access them, leaving nearly 36,0000 children without access to quality early care and education.

Access is particularly challenging for children under age two and those whose cost of child care is subsidized by the government.

“Quality early childhood education plays a critical role in preparing children for success later in life, but the system is strained in Kent County, much as it is across the United States,” said IFF Executive Director for the Eastern Region, Chris Uhl.

In the urban enclaves of Wyoming, Kentwood and Cedar Springs, child care accessibility is a most pressing challenge, as compared to other local communities. Moreover, residents in these areas are disproportionately more likely to experience low-income circumstances, navigate single-parent households, and contend with the demands of multiple children under 6 in homes where all parents work.

The report found that most of the families struggling for child care access reside in areas that had been previously redlined by banks during the mid-1930s to the late 1960s. “We see that 60% of Black, Indigenous and people of color in Kent County are living in these areas and only 27% of the non-Hispanic white community lives there,” said Preeti Rao, senior community data analyst at IFF and one of the contributors of the report.

At the time, The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), a federal agency, produced color-coded maps for cities and towns across the United States. These maps assigned letter grades to areas based on unfounded assumptions about lending risk, with red lines specifically marking the so-called “riskiest” neighborhoods. Unjustly, these neighborhoods were often comprised of Black, Hispanic/Latino, and nonwhite immigrant populations.

Consequently, financial institutions either refrained from lending to individuals in these communities, or, when they did, imposed exorbitant interest rates and fees, rendering borrowing prohibitively expensive. This discriminatory practice obstructed people from acquiring homes in these areas, impeding the accumulation of long-term wealth. The enduring impact contributed to sustained racial disparities in communities nationwide.

“To this day, that historical legacy of redlining and disinvestment has left a lasting impact, erecting systemic barriers that persist to this day,” said Rao.

Many of these low- and middle-income families in Kent County find themselves paying more for child care than their budgets can sustain. Child care providers, operating on slim profit margins, face challenges in remaining open.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommends that families spend no more than 7% of their household income on child care for it to be considered affordable. However, in Kent County, where 7% of the median family income amounts to $5,670, the actual annual cost of child care nearly doubles that figure. For families earning below the median family income, the affordability gap widens even further.

“In the last three years, a family’s eligibility for subsidized care has increased but still does not cover all families experiencing poverty, which is around 37% of children under six years old in Kent County,” said Rao.

Since 2020 subsidy eligibility has increased from 130% to 200% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL).

However, this expansion still falls short of providing affordable child care for many. Families earning above this threshold but below the state’s median income of $63,498 continue to bear the full cost of child care.

Based on 2023 data, the following neighborhoods experienced the most significant unmet need in access to child care: West and East Garfield Park, Black Hills and Grandville Avenue.

Access to care doesn’t have to stay the way it is currently, said Mike Tighe, senior project manager at IFF and a contributor to the 2023 report.

“We need to prioritize improving the access to quality early care for children ages 0-2 and subsidized care for ages 0-5 in some of Grand Rapids’ highest needs neighborhoods,” he added.

One of the simplest ways to do that, Tighe said, is by making it easier for more entrepreneurs to be able to offer care from their homes as licensed child care providers.

“Home-based providers feel that systems are designed more for center-based programs while community-based programs struggle to meet expectations and navigate entry points,” he said.

This is often the case for individuals who, despite not speaking English as their first language, are passionate about caring for children in their communities. They may often have a greater challenge navigating the systems in place to become licensed providers.

“We could address this by looking at developing home-based provider networks to expand the reach of culturally relevant, relevant and responsive child care options, especially in communities of color and neighborhoods with higher populations of immigrant families,” Tighe said.

Some of this work has already started in Grand Rapids as it relates to increasing overall access, advocating for on-site child care programs in places of employment through the MI-Tri Share program.

Via MI Tri-Share, the expense of an employee’s child care is distributed equally among the employer, the employee, and the State of Michigan—a three-way division—coordinated regionally by a MI Tri-Share facilitator hub. This can help parents return to work with the assurance that their children are secure, well-cared-for and have the opportunity to thrive.

“We should also want to co-locate programs with other social service providers, such as in health clinics or after school programs to reduce lengthy commutes and allow families to access multiple services in a single location,” Tighe explained.

But it’s not just about providing more child care spots for families; the expansion eligibility must come alongside professional improvements for child care workers.

“Low pay and reimbursements is the norm for early childhood education workers and providers, and yet that doesn’t equal cost savings for parents and families,” Tighe added.

To mitigate these costs, one approach is to establish a community-mediated model supporting local entrepreneurs in initiating and managing home-based child care programs. This model would provide regulatory, caring and legal assistance as a way to relieve some of the cost burden of these services for providers.

Only half of the available child care spots for children ages 0-5 in Kent County are considered high quality. Right now there are only three quality seats for every 10 children.

“Leveraging resources from Michigan’s Home Visiting Initiative to connect trained child care providers with unregulated family, friend and neighbor caregivers, would help increase the number of high quality spots in the county,” Tighe said.

Making sure child care entrepreneurs know about the different avenues for funding and supporting their business will inevitably improve care according to the report. One of these avenues is through Caring for MI Future, a statewide effort to help child care entrepreneurs open 1,000 new or expanded child care programs by the end of 2024.

“The resources and knowledge are available, and the call to action is clear: collaboration and concerted efforts are essential to ensure that child care is accessible for everyone in the community,” Uhl said. “The challenge ahead is significant, but with collective determination and strategic initiatives, there is hope for a future where all children in Kent County can access high quality child care, setting the stage for their success in the years to come.”

Comments