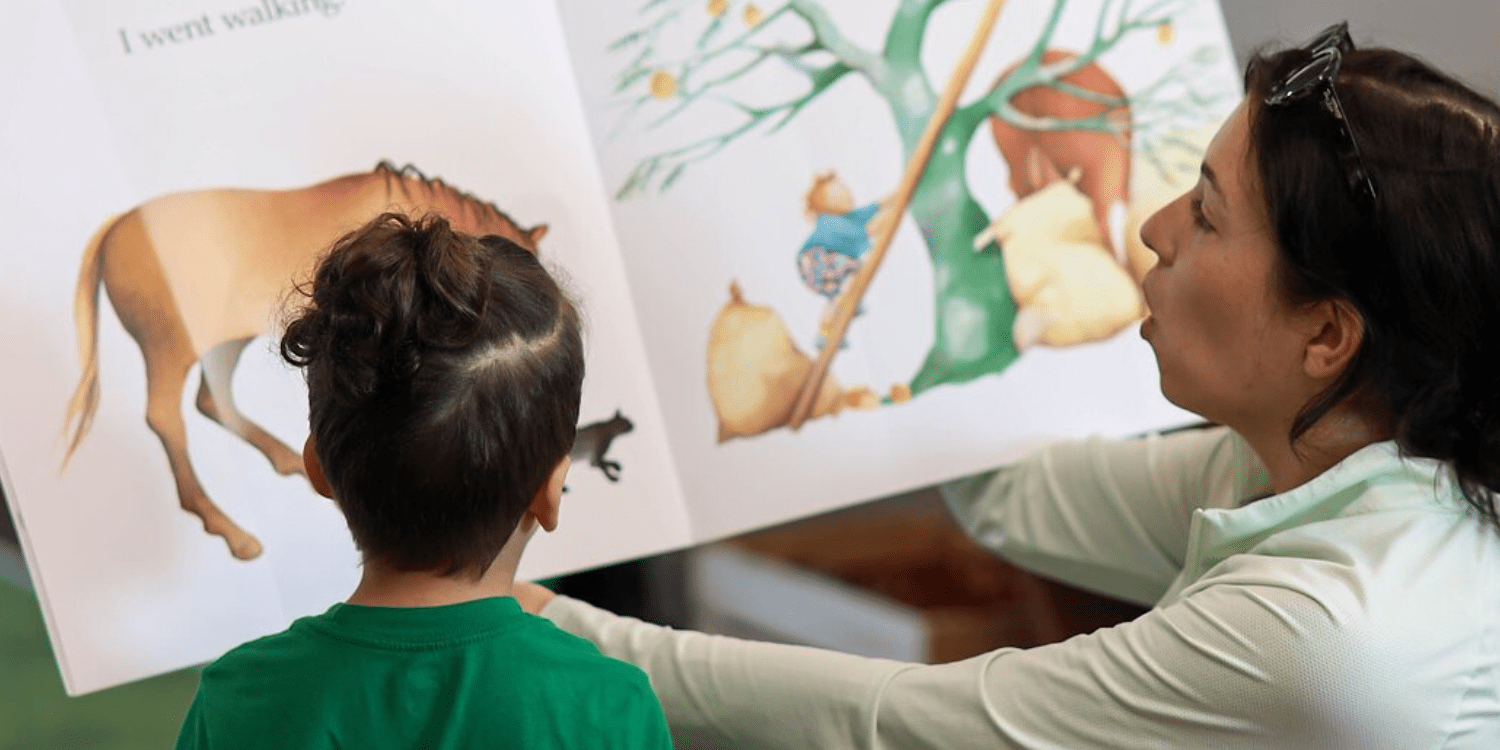

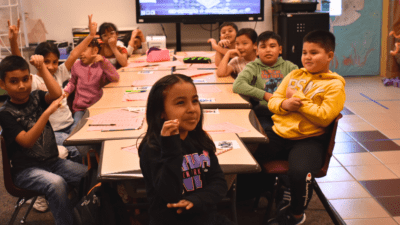

This article, originally published on Rural Innovation Exchange, is part of Early Education Matters, a series about how Michigan parents, childcare providers, and early childhood educators are working together to implement Pre-K for All. It is made possible with funding from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation. Photos by Stephen Smith.

PreK for All will expand preschool options so every 4-year-old in Michigan can access a free preschool education. To guide this evolution of the Great Start Readiness Program (GSRP), the state is seeking input from parents, school districts, early childhood educators, and daycare providers both virtually and through ten listening sessions being held throughout the state. During recent Pre-K for All listening sessions in Detroit and Washtenaw County, attendees raised concerns that removing four-year-olds from home-based and community-based daycare and preschool programs could potentially put many out of business.

But Leslee Barnes, a 30-year early education veteran based in Oregon who is director for the Multnomah County Preschool and Early Learning Division, believes that being flexible and including family-based and community-based early learning centers as providers in programs such as Michigan’s PreK for All can help overcome this challenge in implementing universal pre-K.

“If you’re gonna think about equity, make sure you include the family chapter,” says Barnes. “Also know you’re going to give them additional support that you do not probably need to give the school district to have them participate because a school district has all that stuff built in. But don’t exclude them because it’s harder, because you’re not going to necessarily be able to serve all the children in your community if you do exclude them.”

Listening sessions inform building a preschool program that works for all

Multnomah County is one example of a universal preschool program Michigan can draw from as it moves forward in building its own Pre-K for All program. Announced early this year, the state’s goal is to have the voluntary universal pre-kindergarten for four-year-olds in place by 2027.

“It’s definitely an interesting approach that the governor laid out her proposal for universal pre-k before she actually had a plan for how to implement it,” says Maddie Elliott, policy and program associate for Michigan’s Children. “That’s not how a lot of public policy gets created. So we’re kind of playing catch up in Michigan to figure out how we can implement this in a way that doesn’t harm the childcare system.”

Impacting the current childcare system was a major concern among those who attended the first two pre-k listening sessions hosted by the Policy Equity Group, which the state has engaged to help implement the program. The challenges attendees raised included staffing, teacher pay, prep time, facilities, recruiting families, developing parent trust, meeting current state guidelines and recommendations, and meeting the needs of children, especially those with special needs.

Kristen Sobolewski, program director for First Steps Kent, draws an analogy between preschool and a filled cookie.

“The middle is the sweet stuff. It’s – the children, the education, the care of families. The cookie part is all those other things – regulatory compliance and running a small business. When there’s so much stress on that part, the cookie crumbles, and the sweetness just continues to dissolve. If it’s done right, and we learn from really good models that are working, there’s this opportunity to hopefully have an even sweeter cookie.”

Preschool is not a new concept, universal is

According to the National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER), today only four states – Idaho, Montana, South Dakota and Wyoming – do not offer a state-run preschool that reaches some students.

The concept of preschool dates back to the 1800s. However, it was not until 1965, with the launching of the federal Head Start program through President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society program, that modern-day preschool programs took shape.

With continued research showing the benefits of preschool programs, the seeds for universal preschool programs were planted. In 1995, Georgia was the first state to offer public prekindergarten to all four-year-olds. Oklahoma, New York, and New Jersey followed in 1998.

With so many states having and developing universal programs, a wealth of knowledge on how to establish these programs exists. However, to have a successful program, Elliott believes Michigan needs to invest equally, if not more, in zero- to three-year-old care.

“What has happened in other states and in Michigan when public preschool has been expanded in the past is that, for childcare providers, there’s more of a financial incentive to care for four-year-olds through pre-k than there is to care for infants and toddlers,” Elliott says. “It’s a lot more costly to care for the younger children.”

To help bring early childhood education to the forefront, the governor’s office recently announced the Department of Lifelong Education, Advancement and Potential (MiLEAP), which will focus on PreK for All as well as lifelong learning initiatives.

Elliott says MiLEAP is a step toward helping to view early childhood education as one continuous system that feeds into the K-12 system. However, she would like to see a permanent early education advisory committee, like Washington’s Early Learning Advisory Council, which focuses on developing an integrated education system from birth through age eight.

“In Colorado, they studied how to support childcare providers through expanding public pre-k and found that you really have to provide direct grants to childcare providers who are serving infants and toddlers,” says Elliott. Colorado did a similar study to one that Michigan did on how to expand infant and family child care. “They came to the same conclusion that we really need to provide direct grants for providers who are serving infants and also provide support for family child care providers.”

Connecting with community

By working to help community-based organizations, such as the YMCA, so they do not lose 4-year-olds and provide funding for non-contracted pre-k classrooms, Michigan would be able to offer a mixed-delivery system like in Multnomah County.

In developing its mixed delivery system, Barnes said the county’s program partnered with Micro Resources of Oregon to facilitate payments and Child Care Resources and Referrals for coaching with the goal of all preschool children reaching the same educational outcomes no matter which program they attend. They also worked with other community-based programs that provided food or rent assistance to help educate families about Multnomah’s preschool program. Recently, the county has developed a facilities plan providing grants to help providers add space for classrooms, meet accessibility requirements, and work with housing organizations willing to include space for preschool programs as they develop projects.

“We are also looking at things like, ‘Could people partner with a school – maybe they don’t want to operate the preschool, but one of our providers could be leasing space or there’s a zero lease,’” Barnes says.

Incorporating community-based licensed programs allowed Multnomah County to increase its preschool capacity, provide a mixed delivery that is diverse, and offer convenient options for parents as far as location and hours.

Elliott notes that other states have prioritized community-based programs. About 50% of West Virginia’s public pre-k slots are community-based compared to about 30% in Michigan. New Jersey established a timeline for school districts to collaborate with community-based providers and has about 41% community-based participation in public pre-k. Elloitt notes that New Jersey also prioritized shared-services agreements where providers and public schools pooled resources on food, supplies, supports, and hiring.

Funding and teacher pay

Many states, such as Colorado and Michigan, are funding their universal pre-k programs through state budgets. Even Washington D.C., which, according to NIEER, is currently the only governing body to meet the universal threshold of at least 70% enrollment, relies on government funding.

There are exceptions. New Mexico, which was the first state to make preschool a constitutional right, has a Permanent School Fund that funds the state’s K-12. In 2022, voters approved an additional 1.25% drawdown that provides $150 million to early childhood education and $100 million for other education initiatives.

Sobolewski notes that Oklahoma incorporates preschool funding in the state’s school finance formula, which helped solve another concern, teacher pay. Pre-K lead teachers are paid a K-12 salary range. Washington D.C. also significantly increased its wages for preschool teachers.

In Michigan, a preschool teacher makes about $16 an hour; a childcare provider makes about $12. Elliott adds that despite the push to expand into universal preschool, hardly any of the states have done much to recruit and retain teachers. In Whitmer’s plan, a $3,000 tax credit to childcare and preschool teachers is being provided.

Looking beyond the states

States are not the only source for models when it comes to universal preschool. Many major cities and universities have developed successful programs.

“I think as we look at universal preschool models, we need to look at the cities as well as the states because many of the cities have done some innovative work,” Christina Weiland, associate professor for Marsal Family School of Education at the University of Michigan.

Boston, New York City, Seattle, and Cincinnati have universal preschool programs. New York City has worked out a way to include faith-based providers, Weiland says.

Boston’s Universal Pre-K (UPK), which Weiland and many researchers have studied and used as a model, also tapped into underutilized facilities to build a mixed-delivery system along with placing preschool teachers’ salaries on the same scale as K-12. Boston also has focused on quality by using its own internal research to determine what works and what doesn’t. Boston has adapted a preschool curriculum developed by its own early childhood researchers around the city’s needs and goals.

While Michigan has just embarked on establishing universal preschool, it does have a solid base to build on – the state’s GSRP program received the highest score, a 10, from NIEER’s 2022 State of Preschool report.

Weiland concludes that building on what has been done, taking in consideration evidence-based approaches, and like Boston, looking at what works and what does not for Michigan can help lead the state to create a PreK for All program that works for 4-year-olds as well as for children birth through age 3 and their care providers whether they be home-based, community-based, or based within a public or private school.

Estelle Slootmaker is project editor for Early Education Matters. You can contact her at [email protected].

Comments