Like the world around it, philanthropy is changing. And racial equity must be at the center of that change.

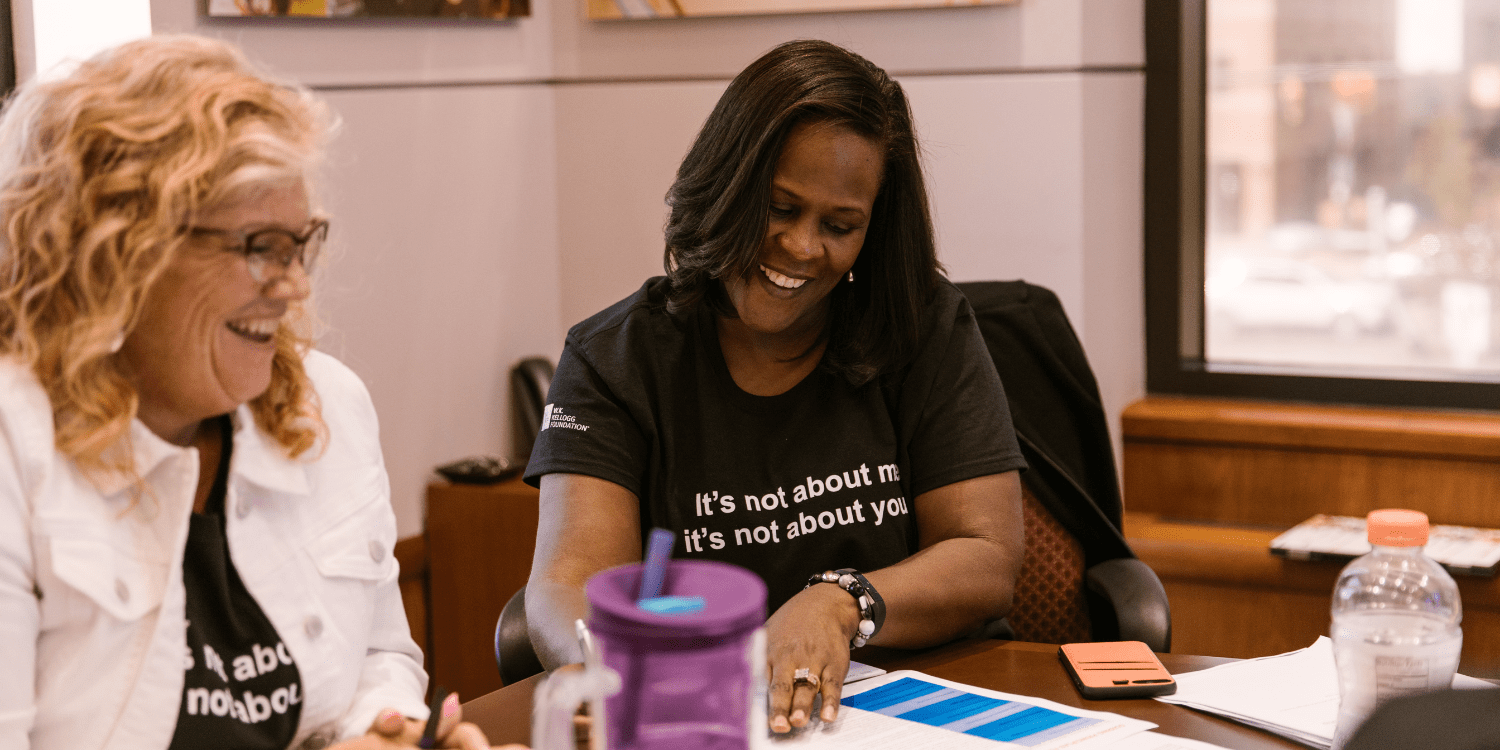

Alandra Washington, VP of transformation and organizational effectiveness

That’s the message WKKF vice president for Transformation and Organizational Effectiveness, Alandra Washington, delivered in a recent article for the Stanford Social Innovation Review (SSIR). She discusses the need for “radical shifts away from traditions, models, practices and approaches that no longer serve our grantees and the communities they serve.” She calls on philanthropy to “acknowledge and repair past wrongs and forge a new path forward with racial equity as a shared goal.”

As a senior leader at one of the world’s largest private foundations, Washington walks the talk. In 2007, the foundation declared its intent to become an anti-racist organization and committed to applying a racial equity lens to all its work. WKKF defines racial equity as the condition where people of all races and ethnicities have an equal opportunity to live in a society where one’s racial identity does not determine how they are treated or predict life outcomes.

Pursuing racial equity in philanthropy means confronting the ways in which philanthropy has historically perpetuated racial injustice. There is an inherent power imbalance between foundations and those who receive funds. If philanthropy as a sector is sincere in its desire to pursue racial equity, foundations must give up some control and power and invite those most hurt by current conditions to have a real say in setting strategy and spending philanthropic funds.

“It’s not enough for communities to have a seat at the table; they need a seat, a microphone, and help adding additional place settings for others to join them.” – Alandra Washington

Historically, communities of color have been vastly underrepresented in the philanthropic sector, while nonprofits led by people of color have been sorely under-resourced. But many inspiring philanthropic leaders are exploring new collective and participatory approaches to grantmaking. They are inviting communities in and giving them real decision-making power. And they are supporting communities of color to become philanthropists and create the change they want to see in their own communities.

In addition to sharing power, organizations sometimes need to look internally and reexamine their entire organizational structure. In 2017, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation embarked upon a process of organizational examination and deep change. Previously structured in a traditional hierarchical way, it reorganized into a networked collective of smaller teams able to respond with greater agility to emerging priorities and philanthropic requests. In particular, when crises hit or needs change – the COVID-19 pandemic, for example – the foundation is better positioned to pivot and respond appropriately.

Foundations can also reimagine the role of philanthropy in society. According to the Monitor Institute by Deloitte (on whose advisory board Alandra Washington serves), grant makers are responding to current needs by pushing the boundaries of philanthropy in four distinct ways:

- Some direct their dollars toward advocacy, policy change and shaping new narratives and beliefs in an attempt to change social systems at their core. Many of these funders invest in movement building and community organizing.

- In other instances, philanthropists attempt to give their money and get out of the way. They eliminate or drastically reduce requirements for grant requests and reporting and give grantees broad discretion over how and where to use their funds.

- A third way foundations are reimagining their role in society is to focus on the innovation necessary to solve our most intractable problems for which solutions are not yet clear or developed. Many of these funders see themselves as early-stage investors or incubators providing seed capital to try out new ideas and see if they work. In their view, the only way to solve our most important societal challenges is to take big risks in pursuit of breakthroughs.

- Finally, there are groups of funders who eschew strict processes and historic ways of operating in favor of being nimble and agile in their response to new emergencies or rapidly changing needs. When crisis strikes, they quickly take stock of the most urgent needs and work to fill them. Predicting their grant-making needs years or even months out would be impossible.

The last three years living through the COVID-19 pandemic, a racial reckoning, and significant political upheaval have taught us that many of our systems are broken. We need change. Those of us who have the privilege of working in philanthropy must start by first looking within and changing ourselves. In the words again of WKKF’s Alandra Washington, “Now is the time to throw out our old playbook of hierarchy, unproductive requirements, and broken status quo…[And] if we’re ready to be agile and adapt so that we can truly reflect and serve our grantees and communities, I’m more sure than ever that we can create a world where every child can thrive.”

It is our moment to lean into the real needs of the moment, allow those who know the problem best to lead, and use all our assets and influence to build a world where our racial identity does not predict our life outcomes nor determine how we are treated.

Comments