In 2017, WKKF made a bold commitment to Battle Creek Public Schools (BCPS), providing an unprecedented $51 million grant to support a top-to-bottom transformation to ensure success for every student. Nearly six years later, the transformation of BCPS tells the first chapter in a story about how policymakers, funders and school districts can work to disrupt a system that’s been stacked against its students for centuries.

Like school districts around the country, BCPS has been shaped by systemic racism.

Five years ago, a coalition of community partners commissioned a study of the education system in the city of Battle Creek, our hometown community. The study uncovered what the community already knew: Even though BCPS served the students and families with the greatest needs relative to the city’s other three school districts, it was given by far the fewest resources.

Many of the factors that created this inequity aren’t unique to Battle Creek or to Michigan. The history of public education in our country is long and complex. Just 75 years after schools were no longer permitted to be openly segregated by law, education was (and still in many ways is) entirely “separate and unequal” due to factors like housing segregation through redlining, drops in property values caused by white flight, and school choice policies that allow students to enroll in districts other than the ones they’re zoned for.

The barriers that Black students and other students of color face, in Battle Creek and elsewhere, come not only from unjust policies in education; kids, after all, don’t go to school in a vacuum. Racist economic, legal and health policies also harm Black families and other families of color, creating further obstacles for students.

WKKF began its partnership with BCPS asking the question: What does it take to undo the impacts of the many intertwined and longstanding policies and practices that have created such an inequitable situation for Black children and other children of color?

The answer to that question came from BCPS Superintendent Kimberly Carter, who came to our partnership having already identified the district’s needs, challenges and potential solutions. Carter, from the start of the transformation, was steadfast in her belief that only an equity-based approach could address the systemic racism that got us to this point.

It takes more than funding to undo systemic racism. It takes a comprehensive equity approach.

“The disparities that students in Battle Creek face aren’t just at the school — they are within the community, and then children come to school having lived in that context,” said Megan Russell Johnson, WKKF program officer. “The district and the foundation’s partnership had to disrupt the historical inequity within the community to create a different future for children in Battle Creek.”

This commitment to equity became the foundation of the BCPS transformation — and has guided every decision of district leaders over the past six years.

What are equity-driven approaches and how do they work?

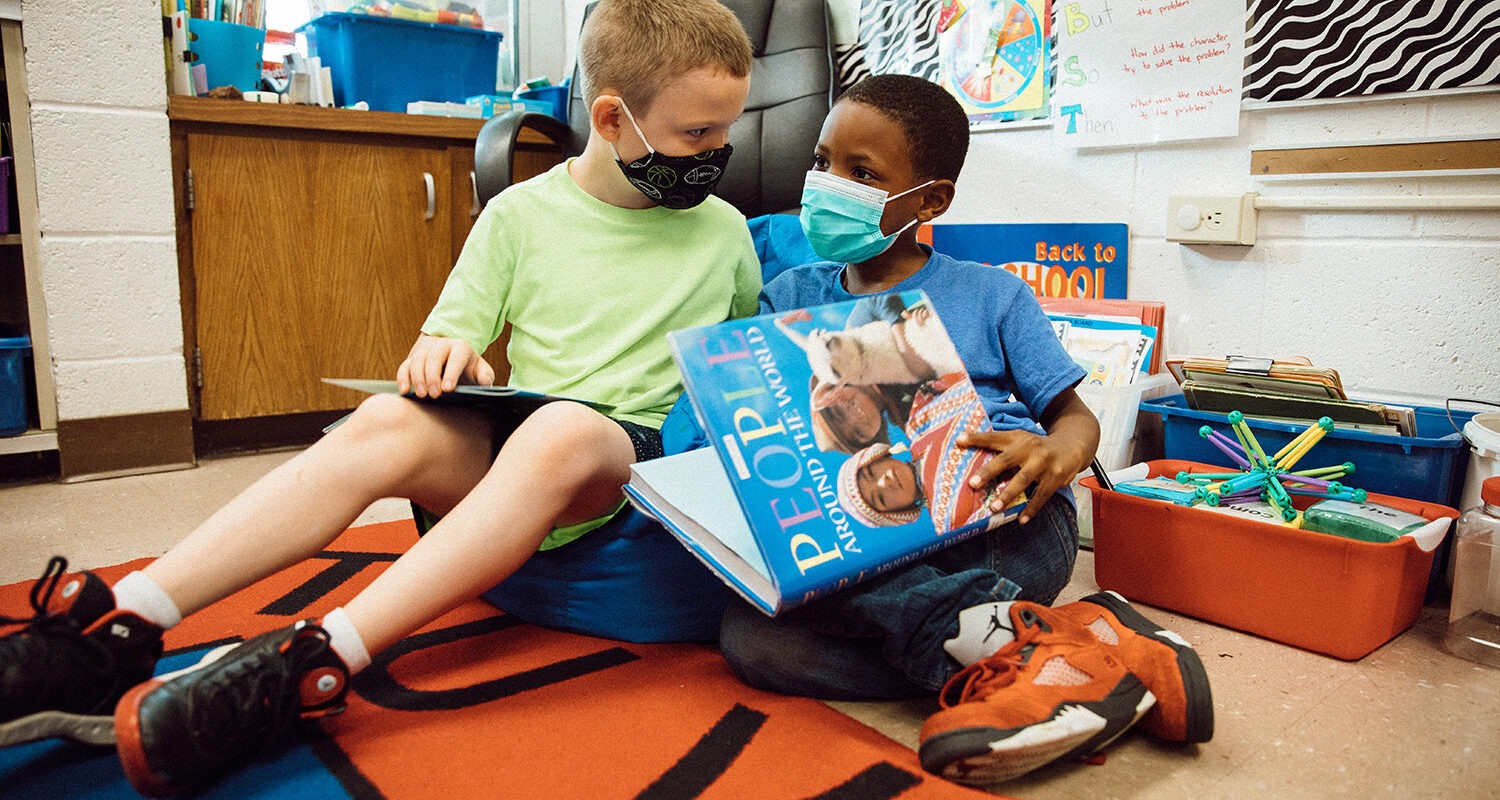

The most visible changes at BCPS over the past six years are the many new educational programs put in place to ensure every student has access to world-class opportunities, from a new STEM-focused school to an International Baccalaureate candidate school to intensive career exposure at the high school. But at the same time, the district has been investing in a comprehensive set of equity-driven approaches to dismantle the barriers that systemically harm Black students and students of color.

Here are just a few examples of equity driven approaches, big and small, in which BCPS has been investing to transform the district:

- Understanding student needs. “We look at every student by name, need and strength,” says Carter, who has made this vision statement a linchpin of all transformation initiatives. The statement acknowledges that sometimes the biggest challenge to creating equity lies outside school walls. As a result of economic inequities, many students, especially Black students, have needs such as food, physical and mental health supports, and safety that must be addressed for them to learn and make school richer for all students.The district has partnered with Communities in Schools to employ school-based site coordinators who refer families to community resources and, in turn, increase access to resources like food assistance, transportation assistance, laundry vouchers, mental health and medical services, and dental care.

- Ensuring students feel seen. Black teachers make up a miniscule fraction of the teaching force — less than 7% — and many Black students are taught by teachers who either don’t look like them or don’t live in their community. With this in mind, BCPS has explored innovative solutions to build a local talent pipeline and fill teaching positions, such as launching a teacher pipeline program with Grand Valley State University and creating a partnership with the City of Battle Creek to help teachers purchase and renovate homes in the city.“A critical part of this strategy is changing the diversity of the workforce and attracting more people into the workforce that share experiences with the children in the district,” said Russell Johnson. “The district and its partners at GVSU have been incredibly innovative in thinking about how to recruit people in Battle Creek, encourage them to go into the teaching profession and then encourage them to stay.”

- Rethinking school discipline. A devastating effect of systemic racism is that Black students are punished far more frequently than their white peers. Changing school discipline practices is a complex undertaking that requires multiple levels of intervention. BCPS created and distributed a guidebook to staff about creating trauma-informed schools, with the aim of rethinking traditional disciplinary practices and creating more positive school environments — a major milestone.But changing the culture involves more than new policies and new hires in the form of new counselors and coaches. It requires helping all school staff understand how past practices have had unintended consequences — “changing hearts and minds,” as Carter says. BCPS partnered with the National Equity Project, an organization dedicated to helping schools and educators increase their awareness of equity issues, to train staff on implementing approaches that help reduce racial and other disparities.

You can’t undo systemic inequity overnight.

“The public education system is perfectly and intentionally designed to get the inequitable results it is getting,” Carter said. “The challenge lies in redesigning the system in order to achieve different results. Big change won’t just happen in a few years. It requires commitment, persistence and patience.”

A lesson from the partnership is that taking on what may seem to be an enormous task — dismantling a history of inequity — is not something to fear. It is necessary and possible, but it takes (and deserves) time.

“Through the course of our history, we’ve lived in a system that has disadvantaged people and children of color,” said Johnson. “We have to be realistic about how long it will take to address the problematic systems in place and then grow new systems that will actually succeed for our children.”

Find out more about the ongoing transformation at BCPS at ChangeStartsHereBCPS.org.

Comments