Our national grantmaking team invests in transformational and structural change for children and families across the United States, with an emphasis on influencing healthcare, employment equity, maternal-child health and early care and education systems. Here team members reflect on Black leaders and Black-led collectives and movements from the past that paved the way for the work our grantees do today in the education equity space.

Educating all children with a racial equity lens

Sakinah (Kinah) Harrison is a program officer who focuses on early childhood education systems, family economic security and narrative change. She mentions the 1954 Supreme Court Brown v. Board of Education decision, making school segregation unconstitutional, as setting the baseline for what we should expect of a public education system that prepares young people to participate in a multi-racial democracy. WKKF grantee the Learning Policy Institute is building the capacity of state lawmakers to equitably fund public education. They report that as resistant as many were in the 1950s to enact desegregation plans with all deliberate speed, public schools and districts “have been quietly resegregating at rates that rival those that preceded the landmark desegregation case in 1954.” Today “large proportions of Black and Latino children live in areas of concentrated poverty, attend under-resourced schools, and face discriminatory policing and mass incarceration.”

As Harrison and fellow program officer, Renee Blahuta, consider their education portfolios, they are inspired by the long line of Black women who have taken a layered approach to addressing inequitable conditions and advocating for their children’s education and well-being.

Building power in education and civic participation

Blahuta’s grantmaking portfolio focuses on affecting positive systemic change and transformation in education systems that serve children from birth to age eight and their families. She says her Black history hero is Allison Brown, who she had “the great fortune to cross paths with and learn from. As executive director of the Communities for Just Schools Fund, a WKKF grantee, Brown constantly championed safe, healthy, equitable schools for Black and Brown children. Throughout her life and in her other roles as an attorney, in philanthropy and as a mom, Allison was a tireless and fierce advocate for racial and education justice.”

Brown passed away in 2020 and leaves behind an organization that cares deeply about public education, aiming to “make schools work for students of color by elevating the power of organizing to create long-term sustainable change.” As Communities for Just Schools Fund highlights, “While a quality education won’t eliminate deeply entrenched social barriers like racism and poverty, it can begin to unlock some of the doors of opportunity that have previously remained closed for too many children in America.”

To thine own powers appeal

In order for children of color to thrive, educational systems and policies need to offer equitable opportunities. At the same time, Black women leaders, like Allison Brown, have needed to build collective power in order to advocate for the systemic changes that support their children’s education. Harrison praises the Alabama Institute for Social Justice, a WKKF grantee, and Mothering Justice for standing at the intersection of education and power-building today and sees echoes of the powerful spirits of Nannie Helen Burroughs and Shirley Chisholm in their work.

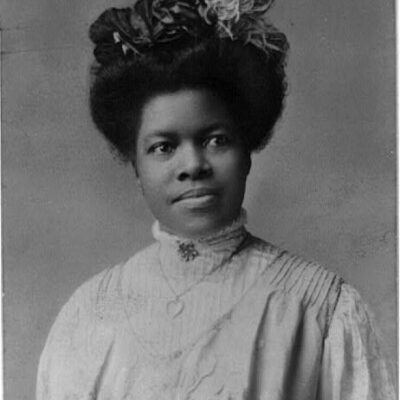

Born in Virginia in 1879, at 26 years old Nannie Helen Burroughs became the founding president of the National Trade and Professional School for Women and Girls in Washington, D.C. Though young for a principal, she’d been denied teaching positions and worked as a janitor and bookkeeper before earning the support of the National Baptist Convention to open her school.

With the motto, “Work. Support thyself. To thine own powers appeal,” the school prepared young women for vocations both within and outside of the home. Burroughs saw no contradiction between practical skill-building and education that expanded the mind, making Black history, Latin and literature requirements for graduation.

Like WKKF, Burroughs knew that for young people to thrive, their parents needed to be able to provide for them. In addition to her work in education, Burroughs co-led the National Association of Wage Earners (NAWE), along with educator Mary McLeod Bethune and business leader Maggie Lena Walker. NAWE aimed to raise the profile of domestic service as a scientific occupation and advocated for fair wages that would impact the women working in domestic service and their children.

A woman who fought for change in the 20th century

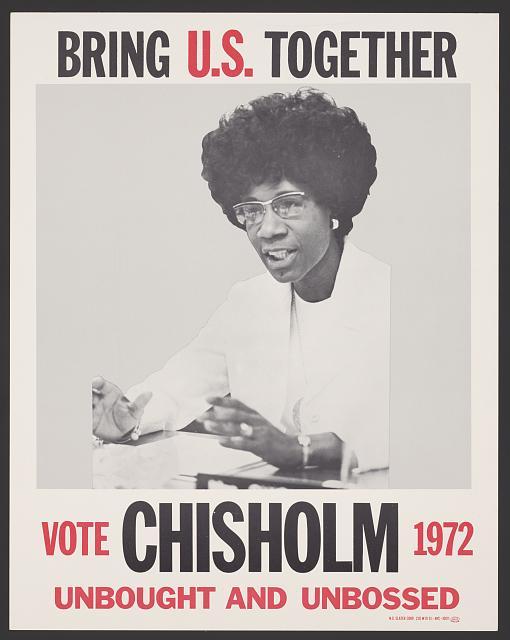

Similar to Burroughs, Shirley Chisholm worked in education and advocacy to improve the lives of children. Born in Brooklyn in 1924, Chisholm had firsthand experience with being an advanced learner at a young age, while also enduring the pressures of poverty. She once said she’d learned to read at three-and-a-half years old and how to write at age four.

Chisholm was a teacher of young children. During the 1950s, she was the director of child care centers in Brooklyn and Manhattan. Gaining respect as an authority in early childhood, Chisholm consulted with the Division of Day Care in New York City’s Bureau of Child Welfare during the early 1960s.

In 1968, Chisholm became the first Black woman elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. Upon taking her seat among legislators, said, “Just wait, there may be some fireworks.” She knew she would have to advocate for her own right to participate in the policy arena.

She was first assigned to the Agriculture Committee. Criticizing the appointment as irrelevant to her Brooklyn constituency, she said: “Apparently all they know here in Washington about Brooklyn is that a tree grew there.” Yet, she used the appointment as an opportunity to continue serving children by expanding the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and create the Special Supplement Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC).

She’d go through a few more hoops – continued public criticism of the House speaker and a second appointment to the Veterans Affairs Committee – before landing on the Education and Labor Committee. While in office, Chisholm played an instrumental role in keeping Head Start intact and co-founded the Congressional Black Caucus.

In 1972, Chisholm became the first Black woman to run for a major party’s presidential nomination. She believed that the purpose of her candidacy was to claim the constitutional right of Black people to participate in democracy and governance at the highest level.

In the end, though, Chisholm didn’t want to be known for her “firsts,” but rather simply as a woman who fought for change in 20th century.

Comments