This post is also available in: Kreyòl (Haitian Creole)

This year’s gathering of the National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) was a remarkably Haitian event. It featured two panels on Haitian journalism and a side event on press freedom that focused primarily on Haiti, and it bestowed awards on two Haitian journalists.

There’s a likely reason for the high interest. Long known for their courage (as captured in the popular film “The Agronomist,” about assassinated truth-teller Jean Dominique), Haitian journalists today – like the population they live among – are constantly challenged by crippling gang violence in the capital, Port-au-Prince, and its economic and psychological ripple effects across the country and diaspora.

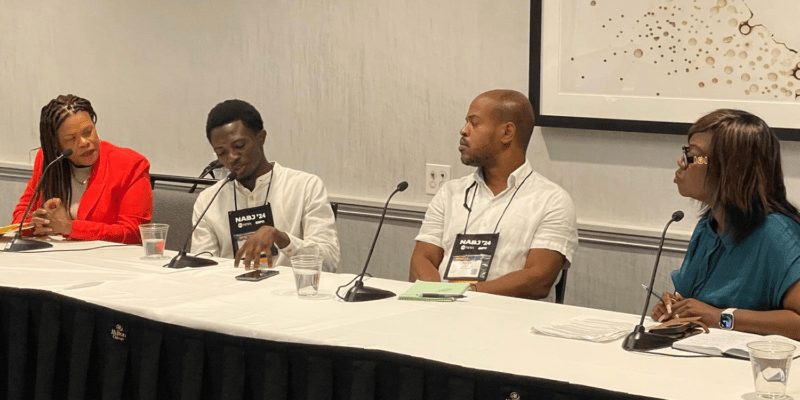

For the WKKF-sponsored panel, “Reporting from Haiti: Taking on Risks and Myths Through Quality Journalism,” moderator Jacqueline Charles of the Miami Herald kicked off the session by describing the context in which the panelists are forced to operate – gangs threatening the survival of Haitian media outlets and the lives of reporters living what foreign news consumers see as “a sexy story.”

The gang problem is all too real, but as the conversation in the room would show, Haiti has many more stories than that.

Reporting from Haiti: Taking on Risks and Myths Through Quality Journalism

- Harold Isaac, a Port-au-Prince-based Canadian-Haitian independent journalist, co-owner of Radio Kiskeya, a radio station co-founded by his late mother, Liliane Pierre-Paul, and a collaborator with several major international outlets.

- Widlore Mérancourt, editor-in-chief of the Haitian media outlet AyiboPost, and regular contributor to the Washington Post.

- Darlie Gervais, a longtime reporter in Haiti who moved to the U.S. and helped launch the New York-based diaspora newspaper the Haitian Times, and now works at the Center for Community Media at CUNY’s Craig Newmark School of Journalism.

- Jacqueline Charles, the Miami Herald’s multilingual Caribbean correspondent with responsibility for Haiti and the English-speaking Caribbean.

The audience of roughly 50 included several young reporters covering the Haitian diaspora in the U.S., as well as prominent journalists from Haiti, including: Garry Pierre-Pierre, founder of the Haitian Times; veteran reporter Marjorie Valbrun; Joel Dreyfuss, a founding member of NABJ and longtime Haitian-American journalist now living in France, and Roberson Alphonse, an acclaimed investigative reporter with Haiti’s oldest newspaper, Le Nouvelliste, now in exile in the U.S. after surviving an assassination attempt. Alphonse won NABJ’s 2024 Percy Zoboza Foreign Journalist of the Year Award for performing “extraordinary work while overcoming tremendous obstacles.”

The panel audience reflected not just a growing interest in the Haiti story but also a rise in U.S.-based journalists of Haitian descent. A discussion that emerged from the panel explored the question of how Haitian-American journalists at U.S.-based media outlets can get their newsrooms to tell more in-depth stories about Haiti and the diaspora. For this, Charles brought in Valbrun, who began her career during the refugee crisis in South Florida as a reporter at the Miami Herald. Her presence helped the audience see that what Haitian-American journalists across the U.S. are experiencing today had been charted by previous generations in Florida.

The challenges they face

As described in Charles’ introduction, the dangers of practicing journalism in Haiti are particularly high for local reporters, who often lack the protections provided their foreign counterparts, are more likely to be sent into perilous situations, and, as locals, stick around after the story is published, living near those who might be unhappy with their reporting.

Darlie Gervais said the young journalists she trained in a Haiti-based journalist “boot camp” are in “constant danger [of] being part of the news, as they could be kidnapped trying to get to their source.”

Other challenges include being ignored by spokespeople, or lied to, mental health struggles and isolation, in part because, as Widlore Mérancourt said, “over the years, friends and colleagues and neighbors have been leaving the country, one by one, and at the end of the day, you are by yourself.”

What is the international media missing about Haiti?

Harold Isaac said that often the foreign media are too rushed to cover Haiti properly. “Haiti’s deep stories develop over time, and sometimes it’s hard to pick up the nuances.” He said they have the resources to deliver compelling stories to their foreign audiences, but they lack “the patience and temerity to deal with the complexity of Haiti.”

Mérancourt described the problem with foreign coverage by quoting Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, who has written and spoken out about “the danger of a single story.”

The single story of Haiti as told by international media, Mérancourt said, is catastrophe. “The danger of a single story… which is to respond to what catastrophe is happening at any particular moment, is a big problem because, as my friend Harold said, it lacks complexity and depth.”

Gervais added, “The system is to fit Haiti into the narrative of a country that is in trouble.” As a result, she said, “they are missing so much about Haiti.” She hopes foreign journalists will read the reporting of their local counterparts before coming to Haiti, to see that there is much to Haiti beyond “that one single narrative.”

In fact, for English speakers seeking in-depth, locally written stories, there are more options today: AyiboPost often has content in English, Le Nouvelliste recently started publishing articles in English, the Haitian Times, which is in English, has been expanding its reporting by journalists living in various parts of Haiti. And Jacqueline Charles, though reporting for a U.S.-based publication, the Miami Herald, continues to cover Haiti, as she says, “as a local story.” Charles, a two-time NABJ Journalist of the Year, this year won an NABJ Salute to Excellence Award for her coverage of the effects of the gang violence on a group of disabled orphans and the push to relocate them temporarily to Jamaica.

So what are the other stories that should be told about Haiti?

The panel provided several examples of the kinds of stories about Haiti that need to be told. Gervais talked about farmers in northern Haiti mobilizing to build canals and improve crop production, and about children giving a concert despite security concerns.

Dreyfuss offered, “The easiest and most reachable story about Haiti, to look at a positive aspect, is the diaspora story,” including successes like the chief marketing officer for Nintendo, and various U.S. university presidents. “The success here is a positive story, but it’s also a reflection that Haitians, given the opportunity, can be successful.”

Mérancourt called for the recognition of professionals who continue to work in Haiti, such as those participating in “the Haiti-based humanitarian system,” because, as valuable as international humanitarian work can be, “we don’t talk enough about the Haiti-based organizations with Haiti personnel trying to do the grassroots job of helping people.”

Another story Mérancourt named: The many Haitian organizations “bringing solutions to the difficulties we are facing,” such as Haiti’s Quisqueya University conducting research that solved a problem with the country’s sorghum crop. “These are not stories you hear in international news.”

Finally, another important and positive story is Haitian journalists themselves, “who can tell stories that change the narrative,” Mérancourt said. That, he said, “is paramount.”

Comments