This post is also available in: Español (Spanish)

All photos courtesy of BBC StoryWorks Commercial Productions

Since the dawn of time, Indigenous birth workers have helped countless generations of babies enter the physical world and begin their life’s journey ion the land that is today called New Mexico. Midwives, doulas, aunties, sisters, mothers, grandmothers, cousins and friends, all had a role in supporting a birthing parent. The birthing practices, rituals and knowledge were closely held and passed down through the generations as part of an unbroken set of sacred traditions that continue today among New Mexico’s 24 Native American Tribes, Pueblos and Nations.

Traditional birth work in the United States extends beyond Native American cultures and communities. By the early 1800s, there were more than 800 “curandera-parteras”—traditional midwives/healers of Hispanic origin—serving families across New Mexico. All communities across the United States depended on midwives and other collective support systems to birth babies. These practices were standard until a few generations ago, when the medicalization of birth and growing dominance of Western medicine began replacing traditional birthing practices. This medicalization of birth often came at the expense of communities of color, with doctors forcibly sterilizing women, operating without anesthesia, and performing invasive and often unnecessary interventions without consent.

Current State of Maternal Health in New Mexico

In New Mexico, the medicalization of birth occurred more gradually due its largely rural and sparse populations. When New Mexico gained statehood, the newly established Department of Health recognized the immense value of traditional midwives, at least until medical infrastructure and providers could be established. Over time, that traditional birth worker system was dismantled through federal and state policies and false narratives that deemed home birth, traditional birthing practices and traditional birth workers as “unsafe.”

Despite significant advances in medical technology and increased spending on maternal health care, the United States continues to have some of the worst maternal health outcomes, especially in communities of color. Many of these adverse outcomes are rooted in historical trauma, racism, poverty and lack of culturally safe providers. In New Mexico, these poor health outcomes are especially striking among Indigenous women. Some of these health disparities include:

- Severe maternal morbidity for Native American women was 60% higher than for Black women and twice as high compared to White women.

- Native American women are twice as likely to experience severe health complications during birth than White women.

- Native American maternal deaths ratio is 129.3 deaths per 100,000 compared to non-Hispanic Whites at 89.4.

- According to “Giving Voice to Mothers,” a report by W.K. Kellogg Foundation grantee Birth Place Lab, Indigenous mothers experience the highest rates of mistreatment from healthcare providers during pregnancy and childbirth, including verbal abuse, exclusion of traditional practices and discrimination.

These sobering statistics provide an important window for understanding how best to address disparities for Indigenous mothers, particularly in a state like New Mexico where 12% of the population is Indigenous and 98% of all babies are delivered in hospitals.

The health and well-being of Indigenous peoples are deeply connected to the land, our ancestors and our cultural practices. The physiological aspects of birth must be nurtured and tended to, but from an Indigenous perspective, emotional, mental and spiritual health are also fundamental contributors to overall health and well-being. Birth has always been a sacred life event with communities embracing their own unique traditions and knowledge systems.

Many communities conduct ceremonies and rituals prior to, during and after pregnancy. Some birth practices include sash belts or ropes to aid in bearing down during delivery, and traditional medicines, herbal baths, special prayers and songs. Burying of the placenta may also play a key role. Whatever the practice(s), they are all meant to bring holistic wellness to the birthing parent, the baby and their family. Tragically, in the Western health care system these practices are often excluded or denounced.

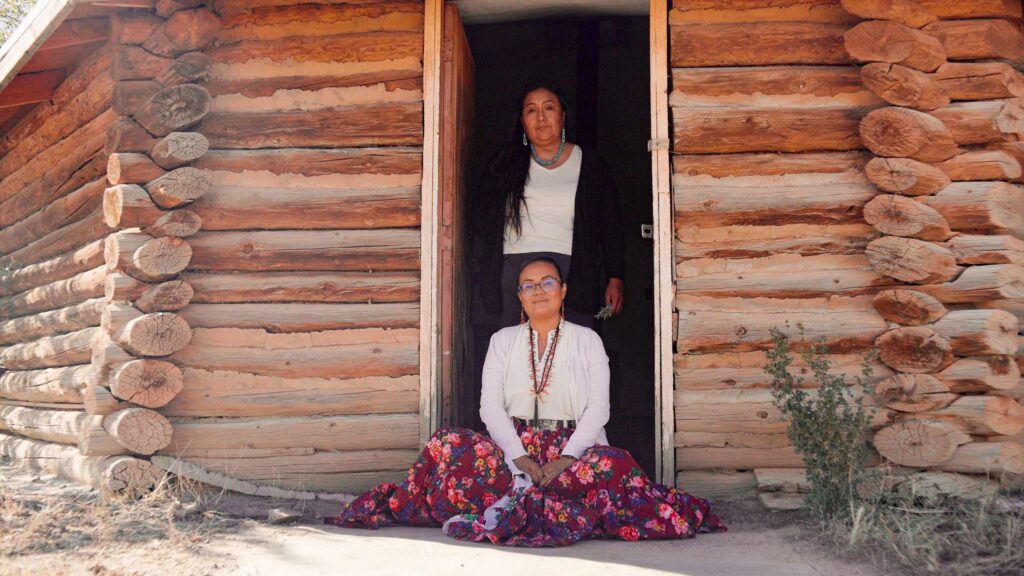

“I didn’t start calling myself a doula; I just thought I was being a good auntie.”

Amanda Singer

Indigenous Birth Doula and Executive Director of Navajo Birthworker Collective

Indigenous-led Advocacy and Solutions to Improve Health Outcomes

A growing movement in New Mexico spearheaded by women-led Indigenous organizations advocates for a holistic approach to birth work that recognizes traditional birth workers and culturally safe birth practices as essential to the ecosystem of birth care. WKKF grantee Navajo Birthworker Collective, led by Executive Director and Indigenous Birth Doula Amanda Singer (Diné/Navajo), is one of the organizations at the forefront of this movement. The Navajo Birthworker Collective works to improve the health of Navajo families providing compassionate, unbiased and accessible care to all birthing families. The collective plays a key role in building out the Indigenous doula workforce, particularly for the Navajo Nation, by hosting a series of trainings for individuals interested in serving their communities as doulas.

“The Navajo, we are a matriarchal society,” says Singer. “Navajo is what unconditional love is supposed to be. Being supportive has always been a part of our teachings. The best description would be: we are aunties. They’re the ones that raised me. And they also took care of me, defended me, protected me. I didn’t start calling myself a doula; I just thought I was being a good auntie.”

Another WKKF grantee in this movement, Tewa Women United, serves many of the northern Pueblo communities in New Mexico. Tewa Women United’s vision is rooted in P’in Haa (Breath of Heart/Life), and P’in Nall (Touching Heart and Spirit) that nurture and celebrate the collective power of beloved families, communities, and Nung Ochuu Quiyo (Earth Mother). Their program, Yiya Vi Kagingdi (Mother’s Helpers), developed an Indigenous doula curriculum and has graduated several cohorts that now serve families across the state.

Both groups have helped reform state-level policies and advocated for better integration of Indigenous birth workers and traditional birthing practices into the local health care systems. Notable victories include:

- Negotiating and securing Medicaid reimbursements for doulas, lactation counselors and increased reimbursement for midwives.

- Influencing the New Mexico Department of Health’s credentialling process to ensure diverse pathways to becoming a Medicaid reimbursable doula.

- Shaping recent legislation that requires hospitals and free-standing birth centers to allow doulas to accompany their patients for certain services.

Other WKKF grantees in New Mexico have allied themselves with this important movement, including the University of New Mexico College of Nursing’s Department of Midwifery, which has doubled down on recruitment and retention practices of Indigenous student midwives, and the New Mexico Doula Association, which now provides scholarships for doula trainings.

While some at-risk pregnancies require a more multi-faceted approach, academic research has demonstrated that a diverse, culturally-safe perinatal workforce that includes midwives and doulas can improve health outcomes, specifically in reducing cesarean deliveries, premature deliveries and duration of labor. The support and expertise that doulas and midwives provide can also reduce anxiety and stress for the birthing parent and baby, which can lead to better health outcomes for both.

This growing movement of Indigenous birth workers is a golden opportunity to lean in to a “Two-Eyed Seeing Approach,” where families can benefit from both Indigenous and Western approaches. We can value both knowledge systems as complementary parts of a whole, ensuring Indigenous parents have the freedom to honor the sacred life event of Birth in the way that is best for them and their baby.

Explore videos and stories demonstrating the beauty and unity that accompany birth. Experience this sacred rite of passage through the eyes of birth workers and the families they serve in Alaska, Mexico and New Mexico.

Comments