The COVID-19 pandemic sparked what Anthony Klotz coined the “Great Resignation,” and now, more than one year after the Texas A&M professor first uttered the famous phrase, it still hasn’t stopped. According to the Labor Department’s latest Job Openings and Labor Turnover Summary, historically high numbers of workers are still quitting, with 4.4 million people voluntarily leaving in April 2022. That’s only slightly down from the 4.5 million workers who left in March.

With high labor demand and rising costs for essential needs like food and gasoline, the best explanation for why so many workers are still walking away from employment is that the pandemic pushed people into a “Great Reevaluation.” Confronted with the fragility of life, Americans decided that work should and could be better. They’re on a quest for employers who respect their humanity and are committed to nurturing more equitable and opportunity-filled workplaces.

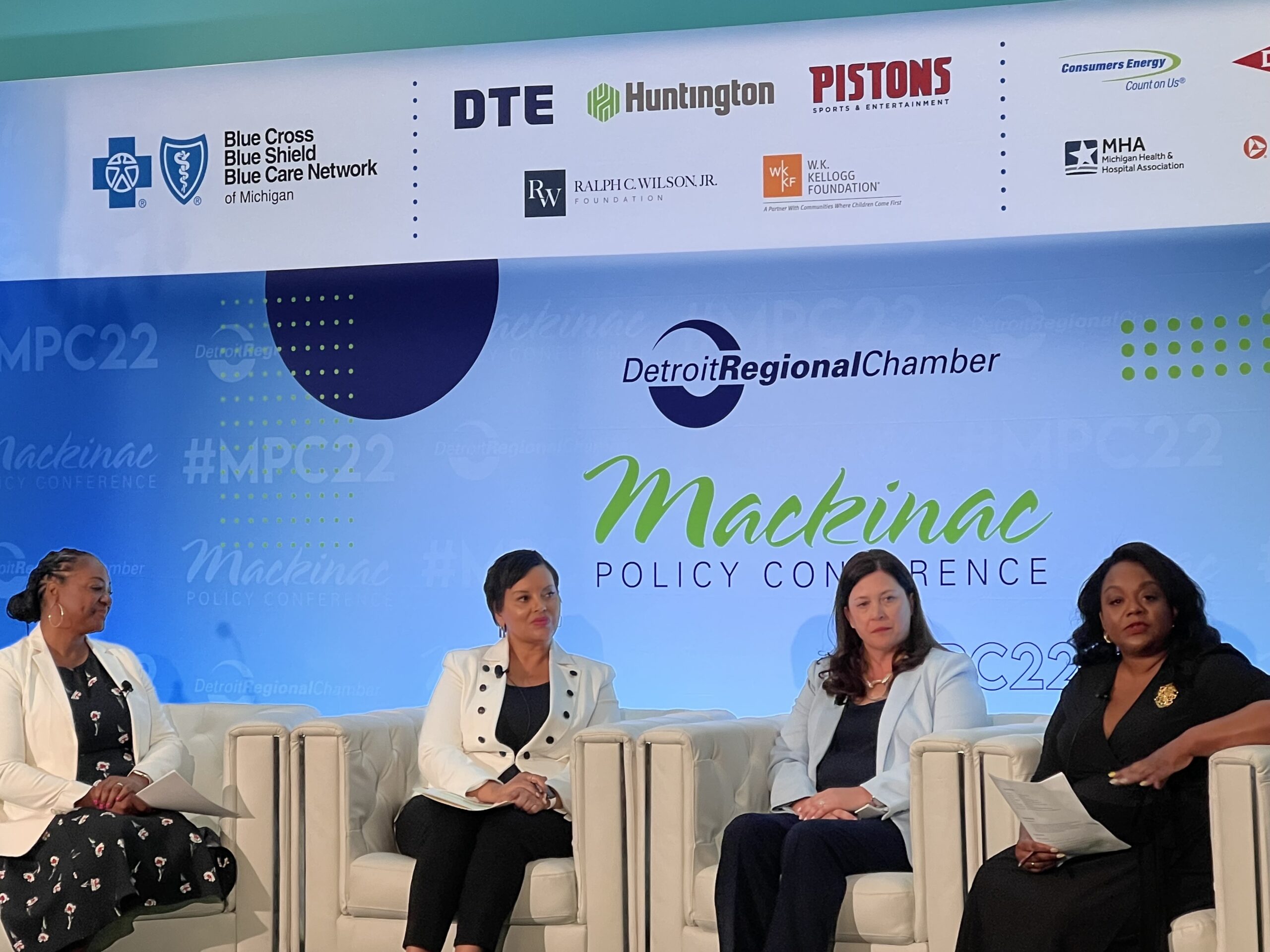

Some employers are heeding the call. A trio of women leading that charge here in Michigan spoke out at the 2022 Mackinac Policy Conference, an annual gathering of Michigan’s business, nonprofit and political leaders. “As employers, it’s important to think about the value proposition we give to our employees and the value proposition we contribute to society,” declared La June Montgomery Tabron, president and CEO of the W.K. Kellogg Foundation. In their panel, “Advancing Equitable Workplace Strategies for Michigan’s Success,” Montgomery Tabron, Shana Lewis, vice president of talent acquisition and workforce programs at Trinity Health, and Cheryl Bergman, executive director of the Michigan Women’s Commission, spoke to moderator Candice Fortman, executive director of Outlier Media, about the actions they are taking to improve the quality of work for everyone, especially women, caregivers and workers of color.

Intentional action is key to truly changing culture in the workplace. Even prior to the pandemic, women have long banged the drum for pay equity, genuine pathways to higher wage jobs, paid leave and affordable, quality child care. For so long, these issues of economic security were presented as personal or private family matters. But COVID-19 changed some things. Child care costs as much — or more than — rent for many families, and over 60% of all women of color earn less than $15 per hour in Michigan, according to an analysis from Oxfam and The 19th. “Our community leaders, business leaders, and policymakers are now talking about child care as an economic driver,” Bergman said.

Savvy anchor employers who need to stay fully staffed and operational in the face of labor shortages are rising to the challenge, partnering with policymakers to build an economic infrastructure that keeps parents at work. One example is the MI Tri-Share Child Care pilot program. “The idea of the pilot is to retain and attract employees; for families to be able to afford child care and to provide some stability for child care providers,” Bergman said.

Designed to help Michigan’s ALICE population (Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed), Tri-Share launched in March 2021 and has the potential to radically change the economic landscape for families that are struggling, but ineligible for federal or state subsidies. It works like this: Employers enrolled in the Tri-Share pilot not only commit to recruiting employees to participate in the program, but they also agree to pay one-third of participating employees’ child care costs. Another third is paid for by the state government or, in some cases, organizations like the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, and the final third is paid by the employees themselves.

“It’s helping some families,” said Bergman. “A family in Traverse City, because they enrolled in Tri-Share, was able to save enough money for the down payment on a home.” How’s that for real world impact?

And employers truly committed to change won’t stop there. “What you find,” said Montgomery Tabron, “is some of these structures and systems have disadvantaged some people and advantaged others…it’s looking at what policies are producing these results repeatedly and [asking], ‘How do we change those so that people have real opportunities to thrive?’”

At Trinity Health, under the leadership of Shana Lewis, it’s been through the implementation of “HireReach” and “R.I.S.E. Up,” two evidence-based employment strategies that help decrease hiring and advancement barriers for people.

HireReach began as a program in Grand Rapids supported by funders, including the W.K. Kellogg Foundation. It uses an evidence-based selection model that takes a data-driven, structured approach to hiring in which employers identify competencies related to job performance, use reliable tools to measure them, and use a standardized, consistent hiring process. HireReach has now grown into a self-sustaining system available nationally, supported by participating employers like Trinity Health. It has helped Trinity Health more than double their hiring of people of color, reduce first year turnover by 23% and reduce time to hire by 16%.

Hire Reach enables Trinity Health to recruit diverse talent, while R.I.S.E. Up, also partially funded by the Kellogg Foundation, and operated in partnership with West Michigan Works! and The SOURCE, ensures their retention through talent and career pathway development and wraparound supports. Under Shana Lewis’ leadership, Trinity Health is undergoing a “culture change and mind shift” and achieving significant results over the program’s three years of operations, including an average increase in wage for advancement per employee of $2.31 per hour and net wage increases for participants of the program of more than $1 million. Fifty seven percent of the program’s participants are people of color. Lewis also works to implement workplace training that reduces racial inequities through implicit bias training programs.

It’s these sorts of actions that create workplace standards wherein everyone has a seat at the table.

“It’s about training people to heal,” said Tabron, who also talked about the journey the Kellogg Foundation itself has taken to become an anti-racist organization. “And healing is about trust-building, relationship building; bringing people together. Healing is at the heart of racial equity.”

This sponsored story was produced in partnership with the W.K. Kellogg Foundation. Sponsored stories are not produced by employees of the Outlier Media editorial newsroom. Read more about our editorial values.

Comments