This story was written by Kellogg Foundation partner Black Like Us.

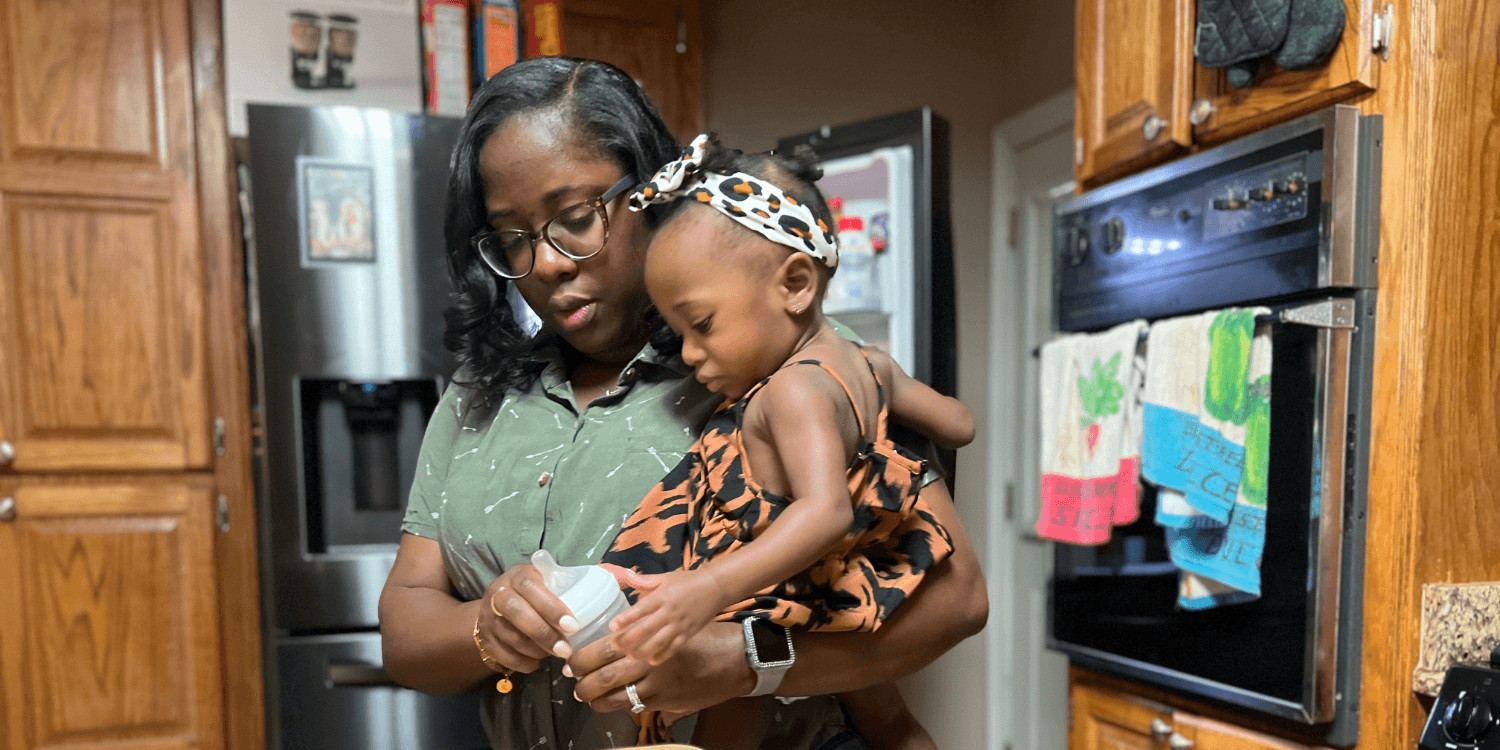

Kacynthia Page had checked all the boxes to prepare for the birth of her daughter. She knew what supplies she needed, had family support and was determined to breastfeed her newborn. But what she wasn’t prepared for was delivering at 29 weeks.

It was the end of June 2022 when Page delivered her baby girl. Just like the early birth, it was also a surprise that her milk had yet to come in, and she feared she wouldn’t be able to breastfeed.

“I went through a lot of emotions,” Page said. “I felt like I wasn’t going to be able to do anything. You feel like you failed in some way…[Breastfeeding] was something that I knew I wanted to do. My husband was supportive and my mom and friends were excited that I wanted to try it. I felt like it would be, I’m not going to say, a better bond, but it was a deeper bond.”

Emotions mounted as Page, who was adamant about being able to give her daughter breastmilk, had to figure things out. That’s when the NICU staff helped her with options, including giving her daughter donated breastmilk.

Though using donated breastmilk isn’t new, for Page, who is Black, the option came with questions and concerns.

“A lot of things came to my mind because I was worried. I was worried that…it was [going to] be contaminated, or it wasn’t my milk, so she wasn’t getting my protection, or whatever my antibodies that I had that I wanted to give her,” Page said. “I was scared about a lot of things. If she was [going to] have an allergic reaction to it or anything like that. It was just a lot of emotions that I went through having her using donated milk first.”

“A lot of things came to my mind because I was worried. I was worried that…it was [going to] be contaminated, or it wasn’t my milk, so she wasn’t getting my protection, or whatever my antibodies that I had that I wanted to give her,” Page said. “I was scared about a lot of things. If she was [going to] have an allergic reaction to it or anything like that. It was just a lot of emotions that I went through having her using donated milk first.”

Page’s use of donated breastmilk was short-lived. Her milk came in within a week, and she could nurse her daughter. But through her ordeal, she discovered that there was a shortage of donated milk.

“When my milk came in, they told me, ‘That’s a good thing that your milk came on in, we were running low.’” Page said the hospital was trying to ration out donated milk for babies who needed it.

“So I just asked, how do I donate if I have a surplus of milk? I didn’t know that you could do it. I didn’t know people just stored milk. I was kind of shocked at that,” she said.

That’s how Page found out about Mother’s Milk Bank of Mississippi (MMBM), an organization that screens and delivers donated breast milk to hospitals to give to families throughout the state of Mississippi.

“Something that we still have trouble with is a lot of people don’t know that we are here and we exist and what we do,” said Mother’s Milk Bank of Mississippi Executive Director Francis De La Rosa.

Located in a small building with a lab, offices and freezer room in Flowood, Miss., just outside of Jackson, the team prepares hundreds of packages of donated milk to distribute to eligible babies in the state.

“We’re really, really small. The main thing would be our lab,” said De La Rosa. “There’s three tables in there with our pasteurization takes working in there. Then we have our analyzer room. Our freezer room is the biggest room here. Other than that, we have offices. So really, really small.”

MMBM is a 501(3)(c) non-profit organization founded in 2010 and is a member bank of the Human Milk Banking Association of North America (HMBANA). Under the guidelines of HMBANA, the organization’s mission is to “accept, pasteurize and dispense donor human milk to premature and ill infants in Mississippi by physician prescription.”

In the past, the organization would average about 100 donor mothers. De La Rosa said in a March 2023 interview that that number had declined to about 67, but the organization has managed to keep up with demand for breastmilk from their clients.

“Although our numbers were low, these 67 mothers that we approved did amazing at dropping off milk and giving their donations. So we were able to keep up with most of our orders,” she said. “So thankfully, the power of those 67 women went really far and wide because we were able to keep up with demand.”

De La Rosa said breastmilk orders vary weekly.

“Sometimes they’re ordering 300 bottles, sometimes they’re ordering 50, sometimes they only want 20,” De La Rosa said. “Other times, it’s like we need 400 bottles. So it varies a lot depending on the hospitals.” According to its 2020 annual report, the organization dispensed 55,142 ounces of breast milk in 2020, up from 49,200 in 2019.

Donor mothers undergo a series of screenings led by a physician, including interviews and bloodwork. They must be non-smokers, in good general health, and cannot use certain medications and/or herbal supplements. Donated milk is also screened for bacteria and calorie count.

“I feel like the process of in which they’re screening to make sure that I’m healthy…that I don’t have anything that I can pass on to the child. So I feel like it’s safe,” said MMBM donor Shanita Mangum, who decided to donate breastmilk after the birth of her son.

Magnum, who is also Black, said before giving birth, she researched the best options for her son and found various groups and information on breastfeeding and the benefits of breastmilk.

“They’re doing everything that they should do to protect the [babies].”

Who gets the milk?

Who gets the milk?

In theory, MMBM’s medical director Dr. Rebecca B. Saenz says, most of the donations would go to Black babies if based on the infant mortality rate in Mississippi. According to experts, Mississippi has one of the highest infant mortality rates in the nation, at 8.3 deaths per 1,000 live births.

Infant mortality is defined as the death of an infant within the first year of their life, and it is measured by the number of deaths for every 1,000 live births. The leading causes of death were prematurity and/or pregnancy complications, labor and delivery, structural birth defects and unexplained deaths. Out of the number of infant deaths, at least half were among infants who were born weighing less than 1500 grams (3 pounds 5 ounces).

From 2019 to 2021, Mississippi’s average infant mortality rate was highest for Black women at 17.6, followed by American Indian/Alaska Native infants at 13.1. White rates were at 12.5, Hispanic 11.4, and Asian and Pacific Islanders had an infant mortality rate of 9.4, according to data from the March of Dimes.

In 2020, the United States infant mortality rate was 5.4 deaths per 1,000 births.

“So, statistically, and if you combine that with the disparity in breastfeeding rates from birth, statistically we can assume…that most of our milk is going to Black babies,” said Saenz.

The CDC says breastmilk offers health benefits that can help reduce those rates. Saenz said breastmilk has been effective in improving the overall health of infants and helps reduce infant mortality through optimized nutrition.

Though Black babies are impacted the most, De La Rosa said the faces of donor mothers are typically White. “We do see a lot more White women donating,” she said. “So I could say it’s not very common for when we do get a Black donor, but we do have some that do come in, and I could say it might be maybe less five or less, but we do have some.”

For Page, it’s about access to information and education. She says if it hadn’t been for the NICU staff, she would have never known about MMBM. She thinks that prenatal care doctors could help let mothers know that organizations like MMBM exist.

“Having more support during doctor’s appointments would help get the word out,” Page said. “At least give people a pamphlet letting them know they can donate breastmilk or getting donated milk can be an option in some cases.”

Overall, the experience of donating was easy and fulfilling, said Magnum, who has also given breastmilk to others outside of MMBM for various reasons.

“I make like breastmilk soap and different things like that,” Magnum said. “But nothing made me feel better than being able to produce enough for my child and to help other people’s families and the NICU babies who really needed help. The process wasn’t too invasive, in my opinion; it was easy and simple and didn’t take a lot of time out of my day to be able to help other people.”

How to support Mother’s Milk Bank of Mississippi

Learn more about the Mother’s Milk Bank of Mississippi. Supporters can make a financial donation or become a breastmilk donor by calling (601) 939-5504.

MMBM holds an annual “Pacing for Preemies Milk Run” to raise money. This year’s race is Sept. 22, 2023.

Comments