No one should give birth alone. Nor should anyone learn how to care for their first baby without support. But, during the COVID-19 pandemic, many people became parents in isolation.

“Many, many, many women gave birth alone.”

Malaika Ludman of Birthmark Doula Collective in New Orleans

“It was stressful to say the least,” says Mercedes Smith, also with Birthmark Doula Collective. “If you experienced a normal birth without complications, you were sent home within 24 hours and for good reason – you didn’t want to stay in the hospital with germs and coronavirus looming. But many women didn’t fully get the resources and support a pre-pandemic mom would have.”

Since March 2020, maternal and child health organizations in New Orleans have supported new parents through the pandemic, protests after the murder of George Floyd, and a Category 4 hurricane. Their approaches drew on a decade of experience in trauma-informed care, originally seeded by Hurricane Katrina, as well as the community-first ethos of the city.

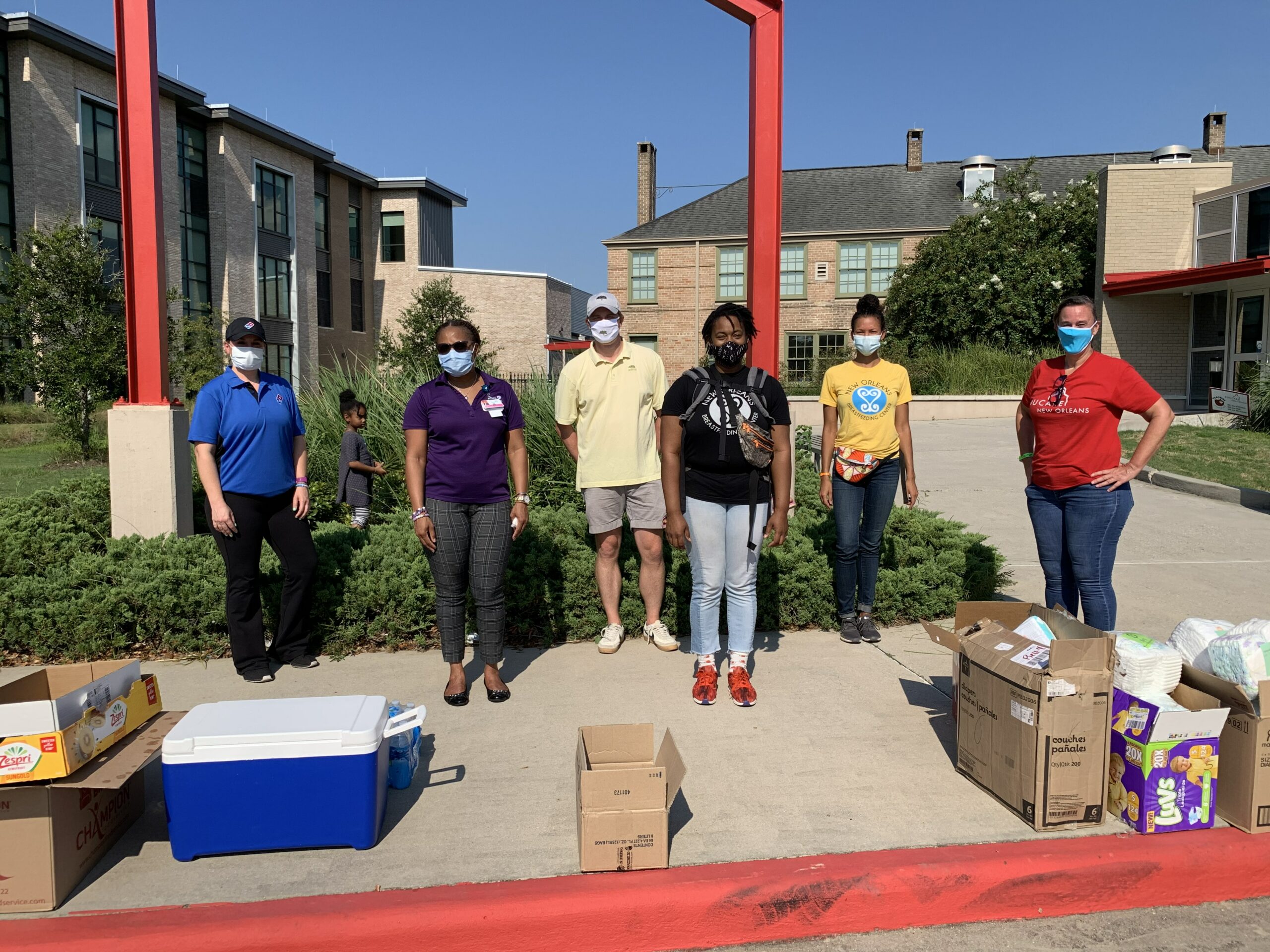

Efforts included virtual drop-in clinics and online lactation consultations, evening text lines and drive-thru baby showers. While these measures sound warm and fuzzy, those in the field say access to real community is integral to the health of moms and babies.

“You’re meant to raise and care for a baby in community with others,” says Ludman.

Birthmark Doula Collective hosted drive through baby showers to provide community support during the COVID-19 pandemic

First COVID hit

Victoria Williams also works for Birthmark Doula Collective, supported by BUILD Health, a WKKF grantee. The collective includes over 40 racially diverse birth workers who assist parents during the perinatal year, from pregnancy through the earliest months of a baby’s life. Mothers across the socio-economic spectrum can access these services, once reserved for the wealthy, on a sliding scale.

Williams describes herself as an early childhood health consultant. She wears many hats – and loves all of them. Before the pandemic, daily life consisted of visiting families in their homes. As a doula, she’d build relationships and learn what physical, emotional and informational support looked like for each birthing person before attending births. Then, as a lactation consultant, she helped new moms build confidence in feeding and caring for their newborns.

“We understood the pandemic was a trauma for all of us – for us, too. For an organization to take the time to understand the feelings of their workers – that’s how you know you’re trauma informed.”

Meshawn Tarver (Siddiq), H.E.R. Institute and Institute of Women and Ethnic Studies, New Orleans

The pandemic, however, disrupted life as she – and the birthing people with whom she worked – knew it. From the outset, Birthmark Doula Collective approached the crisis with a trauma-informed lens.

“We operate as a collective – and I’ll just say Birthmark is a special organization,” says Williams. “We understood the pandemic was a trauma for all of us – for us, too. So we surveyed our perinatal workers just to see how comfortable they were going out and shifted what we do based on the needs of our birth workers. For an organization to take the time to understand the feelings of their workers – that’s how you know you’re trauma informed.”

Williams reduced her home visit schedule to two visits per week – one on Monday and one on Friday. “No more back-to-back visits,” she says. “There was no ‘going into your house and then carrying germs to the next.’ If I had to enter a home, I always came in masked and gloved. If you didn’t feel comfortable with me coming into your home, I could visit you on your porch.”

Going virtual

The collective immediately looked for alternative ways to continue the care they’ve provided for the past decade.

Williams’ colleague, Ludman, says, “The relationship you build with a client is a long-term one. You build a level of trust and understanding with clients that other providers don’t have time for, unfortunately. Our first two to three prenatal visits can last up to two hours.”

The collective quickly set up virtual consultations, but in some cases had to build trust all over again. Williams says, “Lactation consultation virtually was weird at first. We need to see your breasts and baby on the breasts. So, we had to assure women that ‘you’re safe, your privacy is kept, we aren’t sharing the screen with anyone.’”

Once a comfort level was built, parents also started to drop into a daily virtual clinic – sometimes in tears as they tried to figure out parenting during a pandemic, and other times simply to relieve loneliness.

Mercedes Smith, who often staffs the clinic, sees virtual options valuable for new parents, even when it’s safe to resume in-person gatherings. “It’s hard when you have a newborn to plan to leave your house; you think you’ve got it together and the baby has a diaper blowout or is crying and you don’t know why. Online options are an awesome resource.”

Williams, on the other hand, says that even successful daily virtual clinics can’t replace the in-person support many mothers missed. Research done across various countries and regions shows that face-to-face support, including empathetic listening, is critical to postpartum mental and physical health.

“We’re going to pay for the isolation later.”

Victoria Williams, Birthmark Doula Collective

Continue to PART II: Then came the uprising

Comments