“We all come from the body of a woman. Prenatal time sets the foundation for who the child becomes. If you change the vessel the child comes from – her view of the world, her environment, her ability to change all those things – it changes how the child is reared and how they, in turn, change the world.”

Meshawn Tarver (Siddiq), H.E.R. Institute and Institute of Women and Ethnic Studies, New Orleans

Meshawn Tarver Siddiq, founder of New Orleans-based H.E.R. Institute and senior program manager at the Institute of Women and Ethnic Studies, chose to work in maternal and child health as a way to change communities from within, and to work from where all community starts – with mothers. From her vantage point, the stresses borne of racism and faced by women of color directly relate to the health of communities – issues revealed more starkly on the world stage in 2020.

“The uprising and the pandemic were not separate,” she says. She draws from her own lived experience to illustrate the racialized trauma experienced by Black parents. “After the murder of George Floyd, I was more afraid of being pulled over as a Black woman than exposure to COVID. When my headlight was out and I didn’t know how to change it, I was more afraid than going to the grocery store with exposure to a worldwide disease.”

Weathering

Research shows the physical ramifications of racialized trauma on the bodies of mothers and their infants. The racial disparity in infant mortality is wider now than it was when documentation began in 1850, a time when most Black women and their children were enslaved. Black women are three to four more times likely to die from pregnancy complications – before, during or after giving birth – than White women. The numbers don’t improve for Black women in higher income brackets; nor when women have children at older ages. In fact, Black women in their late 20s and 30s are more likely to give birth to low-weight children than teenage moms.

Arline Geronimus, a doctor of science and professor at the University of Michigan School of Public Health, began studying this disparity to understand why race – not income or economics – seemed to wear more on the bodies of Black women and their infants. She looked at stress responders in the body, called telomeres, which serve as “stabilizing caps” in protecting our DNA. Telomeres shorten in length as a natural part of aging and as they respond to stress. Geronimus found that telomeres are often shorter in Black women, and make Black women appear on average 7.5 years older than White women of the same chronological age.

Researchers point out that racism isn’t simply a chronic stressor – it is a chronic threat. Racism impacts a person’s ability to secure housing, employment, proper healthcare – or to make it through a traffic stop – all threatening survival. In addition to premature aging, these threats to survival release hormones, such as cortisol, throughout the body, impacting the cardiovascular system, metabolism and immunity. Breast milk with higher levels of cortisol leads to weight gain and anxiety for nursing infants.

Victoria Williams, early childhood health consultant with the Birthmark Doula Collective in New Orleans, says the stressors of 2020 showed up in the health of breastfeeding mothers and infants. These include the isolation of parenting alone, the murder of George Floyd, and the resulting uprisings.

After being vaccinated for COVID-19, Williams began visiting families in their homes to assist with breastfeeding initiation and noticed many infants experiencing jaundice. She relates this trend to heightened stress, which she perceived aswearing on the bodies of new mothers, especially Black mothers, and being passed on to babies.

Williams says Black women carry more than present-day stressors, but also the traumas resulting from 400 years of slavery. “As a woman, when you’re having your daughters, all your grandchildren are there. All the trauma goes through the generations down through my mother to me.”

The daily drop-in virtual clinic hosted by Birthmark Doula Collective – intended to support new parents in breastfeeding and infant care – offered a space of solace for new parents to process the social unrest of 2020. The Collective includes doulas who are mothers and who have lived experiences similar to the families they serve, offering peer support that acts as a buffer against the psychological stress that also wears on the body.

“Parents are processing so many things emotionally and are not able to process all of it through the body correctly,” she says. “For Black mothers, it’s 10 times worse.”

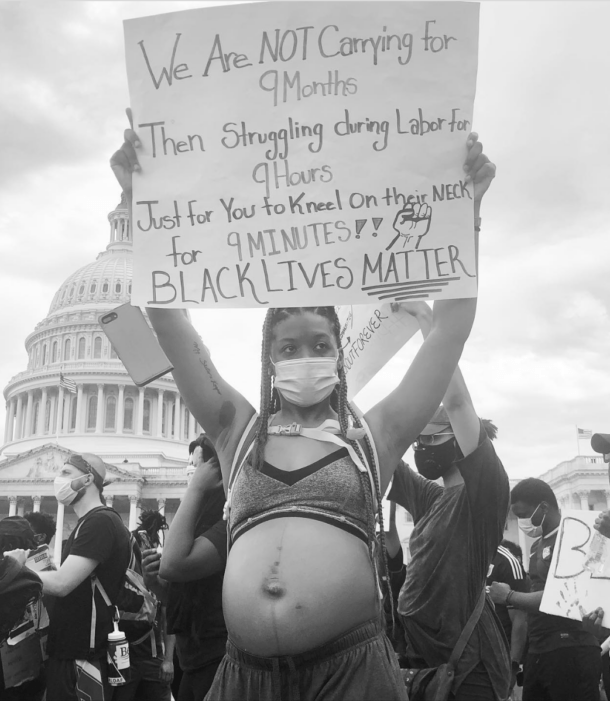

Ludman refers to an Instagram photo that expresses the feelings many parents of color share. “It was a picture of a Black pregnant woman at a protest,” she says. “Holding a sign that said ‘we are not carrying for nine months and struggling during labor for nine hours for you to kneel on their necks for nine minutes.”

Malaika Ludman, program coordinator, says high-profile tragedies in which police use deadly force, “raise questions about the climate your child is going to come up in. For families of color, it brings horrible thoughts to mind of all the bad things that could happen to your child. But it also fosters the desire to reach out to people, connect and find others that are in the same situation as you.

Comments