Story originally published on the W.K. Kellogg Foundation website.

Born and raised in New Orleans, Mischell Davis’ love for her city and its people has deep roots. As the director of an early child care center and an active member of her community, Davis has formed strong, lasting ties with the children and parents in her child care center and throughout the city. When Katrina hit and the floodwaters rushed in, her sense of community was washed away, but never abandoned.

Before the levees broke, Davis, her daughter, eight siblings and a handful of friends fled their New Orleans East neighborhood for Grenada, Mississippi, where they received the news that New Orleans, as they knew it, was gone.

“We couldn’t understand it. We had just seen the news reporters in the streets showing people at home, so we thought we could go back.”

She then reached into her bag, pulled out files of contact information, and began calling all of the parents and teachers so that she was able to learn of their safety.

With so many uncertainties surrounding her situation, and a daughter to provide for, Davis went to Baton Rouge and went about securing a new job, but continued to commute back and forth to New Orleans to help clean up her family members’ home. Starting over in Baton Rouge would have been the easier course of action, but, upon hearing from her teachers and parents about the need for her school to reopen, Davis made the difficult decision to return.

Before Davis even started rebuilding her house, she began work on her school. “The first two years was really hard for a lot of people,” she recalls. “You’re just in survival mode where no one is really living. You’re just existing.”

Amid the hardships, she continued with her mission to get her school back up and running. It took more than a year. It wasn’t until 2011, she said, that things started to feel normal again.

Yet, with all of the new people and projects happening in her city, Davis recognized there was still much work that needed to be done to lift up the city’s parents and children. “With change,” she noted, “there comes good and bad. The parks were better, and so were school buildings. But a lot of teachers were just not ready – not equipped – to meet the needs of the children.”

Parents struggled as well. The transition from community schools to the new system has left some parents in a state of confusion as to how the system works and how to access the resources readily available to them and their children.

“Parents are now working multiple jobs to compensate for increased rent, insurance and in some cases working long distances between their homes and their children’s schools. The number of latchkey children has increased since Katrina. There is a relationship gap in many neighborhoods across the city, and it’s leaving the kids to fend for themselves. Because of these unfortunate situations, parents are experiencing difficulty making it to PTA meetings, school events, etc.”

But she also said the children themselves are different. “Families are still hurting after Katrina. Some families have not overcome the mindset and feeling of, ‘They did me wrong and changed my whole life.’ Our children are hearing that, and they are growing up with the fear and sadness of Katrina.”

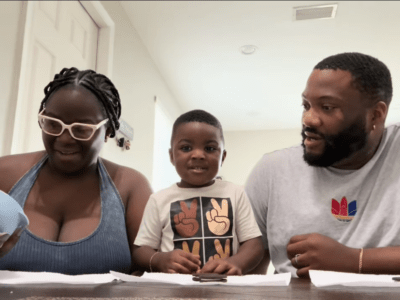

With her passion to help children and parents, Davis began working with the Home Instruction for Parents of Preschool Youngsters program. She is now serving as a para educator for Orleans Parish School Board and a parent advocate with the Parent Leadership Training Institute through the Orleans Public Education Network (OPEN).

Having completed the training institute at OPEN, Davis said she has become an even stronger advocate for and partner with parents, with a better understanding of state systems and how to be effective in reaching the real decision makers to help New Orleans parents grow with their children.

“I’ve always felt that the key to a child’s education is their parent. A lot of parents do not participate in their child’s education because they feel inferior, unsure or are just not aware of how valuable they are. We are here to give them that support, resources, empowerment and voice to be able to speak on behalf of their children.”

“There’s no perfect way – but if we get those parents together from the beginning (of a child’s education) and all the way through, then it works,” she said. “If you get that parent involved at the start, they’re going to say ‘I’m going to do whatever I can to make sure that this school gives my child what every other school has.’”

“It’s my job to show parents how important their voice is. At the end of the day, it’s not the problem – it’s the solution, and I believe I’m part of the solution.”

Comments