I was born into the crescendo of the Civil Rights Movement. In 1967, at only five years old, my hometown of Detroit erupted in rebellion as Black residents were overcome with frustration related to the lack of opportunities and police brutality at the hands of the Detroit Police Department. What followed was white flight and economic instability due to massive layoffs and plant closures by the automotive industry. The uprising of 1967 was the moment that fractured an already destabilized great American city. In many ways Detroit still hasn’t fully recovered, most notably in that it continues to be one of America’s most segregated cities.

I witnessed first-hand the transition of my community and our country. At five years old, my best friends were Ben and Jennifer, the two white kids next door. The block where I grew up eventually only had families that resembled my own. By the time I graduated from Cass Technical High School, its once-diverse student body had become majority Black. My Sundays also started to reflect this changing world and changing city. Growing up, I was able to experience many different faiths, from being an acolyte at a mostly white Episcopalian church to going with my parents to our Baptist church. But as a teenager, making our way down Cadillac Boulevard to Second Ebenezer Church, it felt like a different place. It wasn’t until I arrived at the University of Michigan that my world truly began to expand racially and culturally, as I took my first steps in my journey of firsts and only.

As I watched Ketanji Brown Jackson’s nomination hearings, I was reminded of the implicit requirement of inclusivity that every person of color must master in order to ascend to the highest levels of their profession. If you are a general manager at the local market, a superintendent of a school district, a CEO of one of the country’s leading foundations, a Supreme Court Justice or President of the United States who is Black, or any person of color, you must also be someone who has a community of support that is replete with people who do not look and think like yourself. To be a person of color with ambitions that could take you beyond what you could imagine in adolescence, is to be required to thrust yourself out of your comfort zone, risk being rejected by the majority and navigate the complexities of identity when trying to preserve your authenticity and yet fit in.

I wonder if this is not what some fear most as they consider what Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson’s appointment to the Supreme Court truly means. Judge Jackson’s nomination is a reminder to those most anxious about a diversifying America that they, too, will soon be expected to solicit the partnership of people who do not look or think like themselves in order to achieve their own definition of success.

As the first Black woman, indeed the first woman, ever to lead the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, much like Judge Jackson, I had to have mentors and advocates for my professional success from all walks of life, from many racial and cultural backgrounds. As Judge Jackson told her story, I couldn’t help but consider how rich with diversity of thought and experience her community must be in order to reach a point in her career that her nomination could be possible. I was struck by the remarkable opportunity of her potential confirmation for our country’s long-term success because I know from experience that when one’s personal and professional community is diverse, it demonstrates the value of the equity our democracy promises.

As the leader of a foundation whose goal is to create a brighter future for children and families everywhere, the variety of thought that informs my perspective, drawn from a wide circle of influencers that span the full spectrum of professional disciplines and cultural traditions, is a tremendous value to my ability to fully understand the barriers that need to be dismantled for children and families. I am deeply connected to the work because not only do I see myself reflected in our mission and grantmaking priorities, I also see the children and families who may not look like me, but must be considered so no one is left behind. I am able to show up as a leader with the empathy and emotional intelligence necessary to embrace new and disruptive solutions to long-standing challenges that are linked to our country’s racist past.

Similarly, the value of Judge Jackson’s story can fill a void in the Supreme Court’s ability to fully appreciate the impact of its decisions on the lives of millions in a country as diverse as ours. Indeed, Judge Jackson comes from a community denied constitutional rights for centuries in our country, and that experience of exclusion carries its own influence in a role so closely tied with ensuring equal justice within the bounds of the Constitution. If my claims, so far, seem like conjecture, consider the volumes of published research showing the variety of ways in which diverse leadership can be transformative.

For example, an extensive McKinsey and Company study found that corporate board and executive diversity directly lead to improved financial performance, increased long-term profitability, higher employee satisfaction, and improved organizational practices.

In another example, the Office of the Illinois State Treasurer reviewed extensive academic and practitioner research on the impact of gender, racial, and ethnic board diversity. The results of the review were clear: “companies with a diverse board, inclusive of gender and race/ethnicity, are better positioned to execute good governance, effective risk management, and optimal decision-making, as well as enhanced customer alignment, employee engagement, and transparency, as compared to those with laggard board diversity.”

We are strongest when all of us are represented across every facet of American life. As the first Black woman CEO of a foundation that is making a difference for children and families around the world, I can say with full confidence that the real privilege in succeeding is having the prerequisite of inclusivity, to befriend, consider and connect with those who do not look like me or share every aspect of my experience.

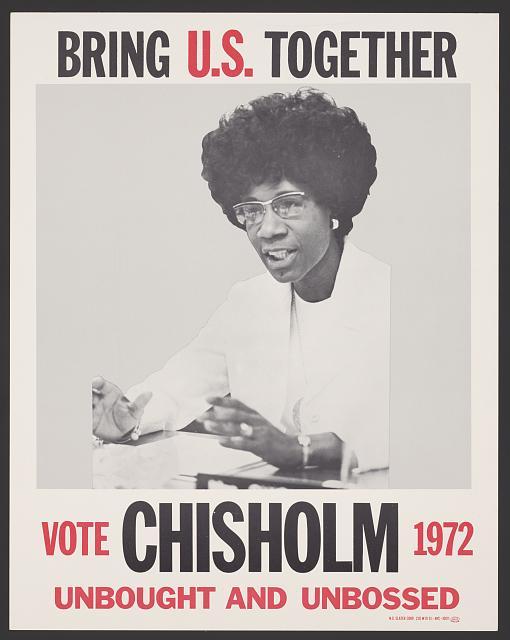

In this moment, I am reminded of Shirley Chisholm, the first African American woman in Congress and the first woman and African American to seek the nomination for president of the United States. She didn’t want to be defined by being “first” or “only” – “I don’t want to be remembered as the first black woman who went to Congress. And I don’t even want to be remembered as the first woman who happened to be black to make the bid for the presidency. I want to be remembered as a woman who fought for change in the 20th century. That’s what I want.”

Judge Jackson’s nomination is an important step forward to demonstrate the value of representation and what it can mean for us all. We have an opportunity to witness history in the making, and that is nothing to fear.

Comments