Story originally published on the W.K.Kellogg Foundation website.

Ten years ago, Darren Alridge was playing ball with his neighbors in the Lower 9th Ward, anticipating the start of eighth grade. He remembers riding bicycles with his friends up and down the levee behind his house – the first levee to eventually break.

“Everything was going well, up until that moment,” he said. “Then, Katrina came.”

Hurricane Katrina quickly washed away Alridge’s childhood and the close community that had protected him.

The oldest son of a single mother of four, Alridge had never traveled outside Louisiana before the storm. Afterward, he and his family fled to Houston, then to St. James Parish, where they lived with relatives for a year. The disruption was difficult for Alridge, who began to struggle in school.

His mother moved the family back as soon as permitted, although the storm left his neighborhood unrecognizable.

“When we got back, we barely had things to go home to. None of our cars were in the driveway…the house had floated into a neighbor’s yard. Some of our stuff was just scattered all around the neighborhood. You really couldn’t find too much of anything,” he said.

As the family fought to re-establish their roots, Alridge returned to classes held in trailers with no books and few materials. “The K-12 system failed me after Katrina. It was just a teacher and a book and whatever they tell us, we have to do, so it really wasn’t helping me, and I began to get into trouble.”

During this time, his mother suffered a shoulder injury and was no longer able to work, thrusting Alridge into adulthood as the family provider at 16. It quickly became clear that the money he earned cutting grass and washing cars was not enough to make ends meet.

“It was getting harder and harder. So it pushed me to the street, where I started to hang out with a bad crowd. We needed the money, so I began to sell drugs.”

In 11th grade, Alridge dropped out of school. Shortly after his 18th birthday, he was arrested and spent three months in jail.

A judge then presented him with two options: spend two years in prison, or earn his GED and get a job. He chose the latter. Two days after his release, Alridge walked through the doors of the Youth Empowerment Project (YEP), right across the street from his house. His probation was arranged so he could successfully complete community service, education and work. In that moment, his perspective and life changed.

YEP helped him finish school, connect with a mentor, land a job and arranged transportation so he could get to work.

Alridge soon knew, “This is where I’m going to graduate from. This is where I’m going to walk across the stage and make my mother happy.”

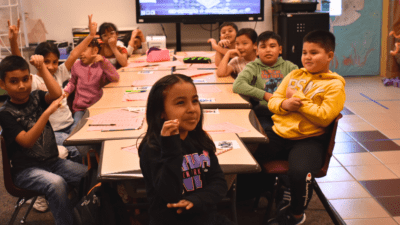

He is now married and a proud father of three. He works for YEP as a mentor and at Cohen College Prep as a para-instructor in its GED program.

“Mr. D,” as his mentees call him, found that his story resonates with other young men, as his previous life mirrors their lives now. He tells them he worked hard to steer in a positive direction.

I grew up down the street. I know what these kids need. Some of them need love. Some of them need support. Some of them need shelter … I do whatever I gotta do to make sure another child in another home is happy.

Alridge acknowledges the challenges of growing up without a father at home, which motivates him to be the best father he can to his children, all of whom live with him.

“Me and my family had to rebuild a happy home, and it’s hard to do when you don’t have a father figure in your life,” he said. “One parent can’t do it all. It pushes their sons to do bad things to provide for their families. I see these kids with no fathers in their life, and it’s pushing them to do bad things in the community. When they can see that ‘Mr. D grew up in the projects, graduated, got his GED and is giving back to his community,’ they can see they don’t have to sell drugs or steal or do bad things.”

The transformation in his own life is a reflection of the transformation that he sees in his community.

“I feel like the community has recovered and is getting better than it was. There’s so much good going on in the community that you can’t do any wrong being here. It’s pushing out the bad. It’s becoming a better place and is going to be a better place.”

Comments