“The COVID-19 pandemic is a singular event,” says Harvard University T.H. Chan School of Public Health Professor David Williams. “There has never been a pandemic that changed so many lives in such profound ways.”

Dr. Williams speaks about the coronavirus from a rare vantage point. As a researcher, he is a pathbreaker, innovator and relentless chronicler of the complex ways that socioeconomic status, race, stress and racism affect health in the U.S.

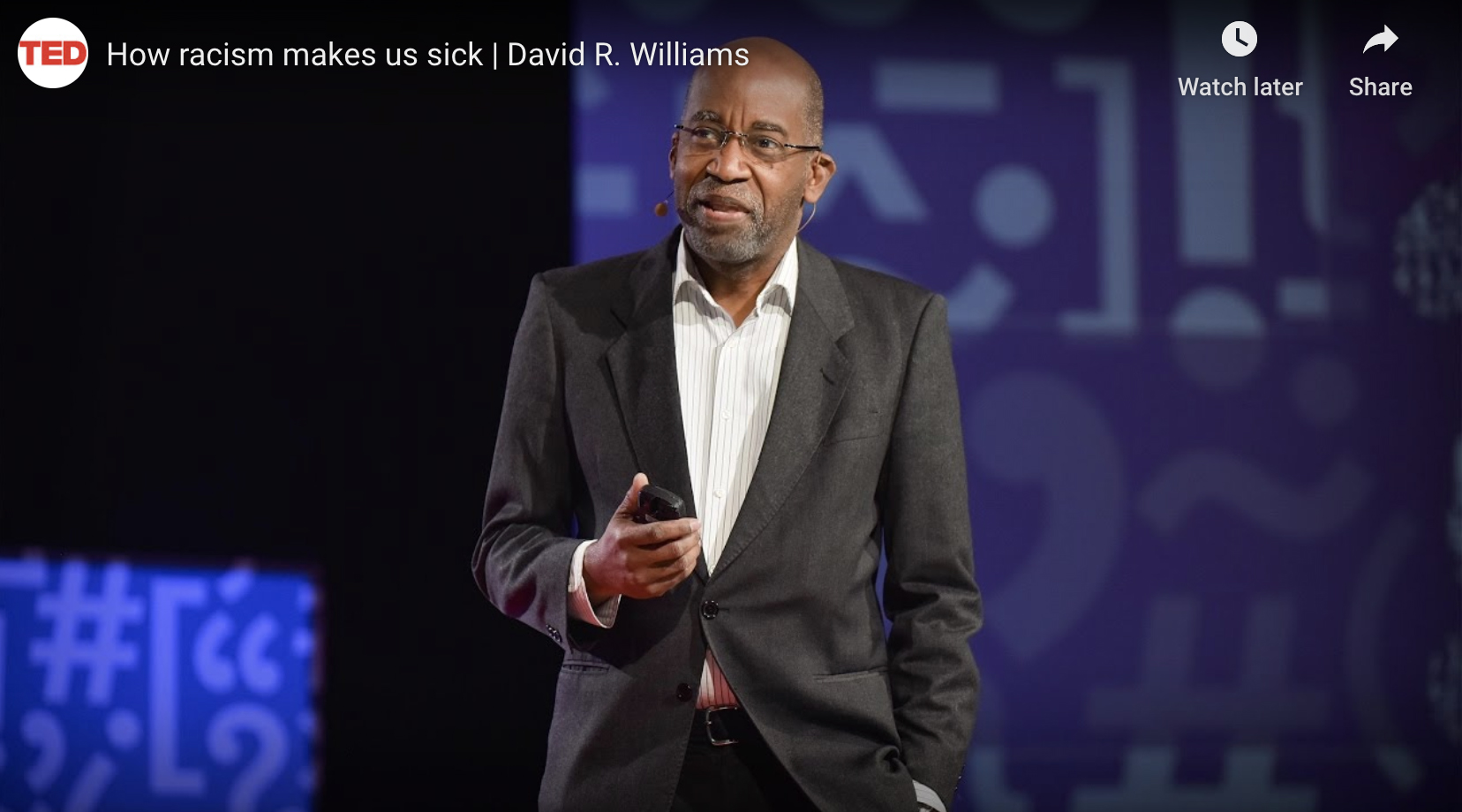

A sociologist and chair of the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences at Harvard, Williams is the author of more than 475 scientific papers and developed The Everyday Discrimination Scale — the most widely used measure of experiences of racism in daily life. As a member of the National Academy of Medicine (formerly The Institute of Medicine), the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the National Academy of Sciences, his insights and analysis resonate with peers. But lay audiences respond to Williams’ research, too. His 2017 Ted Talk, How Racism Makes Us Sick, has more than 1.3 million views.

The W.K. Kellogg Foundation was an early supporter of Dr. Williams and his research. A member of Kellogg Foundation networks for more than three decades, his scholarship has deepened our understanding of the social determinants of health, implicit bias and other factors that shape community well-being. Today, Williams serves on the W.K. Kellogg Foundation’s Solidarity Council on Racial Equity (SCoRE) and joins his voice with other thought leaders committed to widening the lens on equity.

From the Ted Talk stage, David R. Williams presents about why race matters so profoundly for health. This video was produced by TEDMED.

So when he considers COVID-19’s disproportionate impact on communities of color, Williams says he is saddened, but not surprised.

“This unique moment has shone a bright light on stark inequities that have been under the surface and existed for a very long time,” he says.

In his mind, however, the widening awareness holds some promise “because people aren’t motivated or mobilized to solve a problem that they’re unaware of,” he explains.

“The coronavirus did not create racial inequities in health. It has just uncovered and revealed them. These disparities have long existed in the U.S., and persist across leading causes of death, from the cradle to the grave.”

Dr. David Williams Tweet

COVID-19 By the Numbers

Certainly, evidence of the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on people of color has been devastating and consistent.

Reacting to these damning numbers, media stories run the gamut from exploring preexisting conditions (asthma, diabetes, hypertension, heart disease) to blaming people for “poor individual choices.”

Neither approach explains what’s really behind the numbers, he says.

People and their communities are not to blame for becoming ill. And an explanation for the prevalence of chronic health issues in communities of color requires a closer look at our larger culture.

“In the U.S., Black people and other people of color live in conditions generated by social policies that create unequal outcomes across a broad range of domains that ultimately impact health,” Williams says.

“The coronavirus did not create racial inequities in health,” says Williams. “It has just uncovered and revealed them. These disparities have long existed in the U.S., and persist across leading causes of death, from the cradle to the grave.”

Finding the Fault Line beneath COVID-19 Numbers

Williams presses us to consider root causes when we consider the impact of COVID-19. Why, for example, are African Americans more likely to suffer from certain chronic diseases in the first place, and at younger ages than Whites? Racial discrimination is a contributing factor, according to Williams.

The Everyday Discrimination Scale helped researchers show how discrimination of any kind (race, ethnicity, age, gender) is a chronic stressor that correlates to health outcomes. The more significant the discrimination a person experiences, the poorer that individual’s physical and mental health is likely to be.

Williams observes that discrimination that occurs as people of color navigate their daily lives leads to disparate life expectancies. “Researchers use terms like accelerated aging, premature aging and weathering” to describe the effect, he says. “Black people in America are literally aging more rapidly than Whites, biologically.”

“Some of our most impressive heroes are in the health care workforce — people who are putting their lives on the line every day, going to work with good intentions and desiring to do the best for all of their patients. But race is very salient in American society.”

Beyond everyday stressors, Williams notes overwhelming evidence that Black people and other persons of color encounter bias and discrimination in health care settings in the U.S., where they receive inferior care.

“As we battle with the coronavirus, some of our most impressive heroes in the United States are in the health care workforce—people who are putting their lives on the line every day, and going to work with good intentions, and desiring to do the best for all of their patients,” said Williams. “But race is very salient in American society.”

A positive and necessary outcome of the pandemic, says Williams, is recognizing that our “health care workers must be trained differently, with a racial equity lens and a strong emphasis on equity and anti-racism.”

While Williams sees the pandemic as singular, he believes this moment offers opportunities to live out the lessons of the civil rights movement.

“Then, television was the medium that showcased inequities. And a movement that saw how unacceptable the situation grew out of that,” he said.

“With the coronavirus, it’s up to us to say, ‘We cannot live in a society like this. We have to do better.’”

Comments