Niwiidosedimin means we walk together in Ojibwe. It’s also the name of a project of the Wiikwedong Early Childhood Development Collaborative in the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community (KBIC) on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, where educators are discovering what parents, grandparents, caregivers and intergenerational supportive adults envision for their children.

Wiikwedong participates in the Indigenous Early Learning Collaborative (IELC), a program of WKKF grantee Brazelton Touchpoints, along with Native communities in Minneapolis, Seattle and Hawaii.

Four programs serve the youngest members of the Keweenaw Bay Tribal Community: KBIC Pre Primary Program, KBIC Head Start, Keweenaw Bay Ojibwa Community College Little Eagles (Migiizinsage) Great Start Readiness Program, and KBIC Health Systems home visiting program. According to Wiikwedong’s project coordinator, Cheryl LaRose, participating in IELC opened opportunities for all four programs to break down silos and learn together. As a community, they devised a five-year strategic framework and then chose two areas of primary focus. The first focus is on culture and language learning in all early childhood classrooms, and the second is to develop a resource center to support educators with the first goal.

LaRose names culture as a significant building block for children’s identity, and identity as an essential foundation for life.

“I’ve been in the early childhood field going on 40 years. It’s about knowing who you are,” LaRose says. “A lot of issues as we are growing up are about identifying: who am I? What are my beliefs? What are my values? When you know that at a young age, you end up being a strong person.”

Cheryl LaRose, project coordinator for Wiikwedong

“We’ve always done the easy work first. Culture and language always got pushed to the back burner. With the IELC partnership, we pulled language and culture to the forefront,” says LaRose.

The babies will bring the culture back

Educator Lisa Denomie says culture and language have been the hardest components to integrate into the early education system, because adults’ connection to the culture has been severed for generations. For her, the presence of an old boarding school building on the reservation presents a continual hardship, which is why she strives to reclaim language and culture with the children, staff and community.

“I’ve told our Tribal Council, if you want to reach out to the people and bring our culture and language back, you need to start with the babies,” says educator Denomie. “They’re going to be the ones that bring it back.”

Denomie directs the Pre Primary Educaton Program for the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community and also provides language and culture lessons to the reservation’s other early learning centers. She presents the Seven Grandfather teachings on the virtues that lead to a good life incorporated with storytelling. She’s made flash cards with the Ojibwe alphabet for all the classrooms and introduced the Talking Stick to help children “learn the skills of turn taking, listening, learning from sharing and most importantly having a voice with no interruptions.” Staff and community members are currently working together to make regalia for children for the four sites to use during pow wow dancing, home visits and classroom activities.

As the full-time director of one program, she says she’s “sprinkling” cultural teachings into other classrooms, but hopes one day to be the Anishinaabe kwe (woman) whose sole focus is cultural revitalization.

“I get a little choked up here,” she says. “I didn’t have any language and culture growing up. It wasn’t until 1978 we were [legally] able to practice our ceremonies. So, I didn’t grow up with it.”

Lisa Denomie, educator

Oppressive laws and institutions affected her family’s ability to embrace their culture. Denomie remembers, “My mom never talked to us about our language and culture. When I would get teased in school for being Indian, I didn’t even know what Indian was. I had to heal from all that. It took many years for me to thrive. Now I’m spreading my wings out to grow.”

Denomie’s healing process included apprenticing with Grand Instructor Earl Nyholm Otchingwanigan, who assisted her in becoming literate in Ojibewemowin (the Ojibwe language). Adults in the community also share what they know with one another to fill in the teachings.

Revitalizing culture for everyone

For the Wiikwedong collaborative, cultural revitalization involves everyone who educates Native children in Keweenaw Bay, including many Non-Native teachers.

LaRose says, “As Non-Native educators, part of the healing is for us to understand what we, and our ancestors, did. It’s hard to hear. But, in order to serve Native families now, we have to understand our connection to that history.”

As LaRose says, “We live in a community that is Ojibwe, and we all need to know the culture.”

Educators, parents, elders and caregivers all participate in cultural learning. The collaborative hosted a culture camp attended by 50 teachers. LaRose says those fifty teachers reach hundreds of families.

Terri Swartz, program director for KBIC Head Start, collaborated with the community to revitalize Grandmother moon ceremonies, which occur during each month’s full moon. “It’s a time for the women to gather around a fire, gather strength and put your life’s concerns to the Grandmother,” LaRose describes. “Grandmother takes care of you and helps you. It’s a time to strengthen and release.”

The Wiikwedong collaborative also hosts children’s memorial walks and water (nibi) walks to teach the Indigenous tradition of honoring one’s relationship with all of nature, and particularly raising the awareness of the state of our water.

For the Ojibwe people, nibi is life, and education can help ensure healthy rivers, lakes and oceans for descendants to enjoy in the generations to come.

Kim Swanson is the director and teacher at the Little Eagles’ (Migiizinsag) Great Start Readiness Program, a service of the Keweenaw Bay Ojibwa Community College to suppport children as they prepare for kindergarten. She says the Wiikwedong collaborative helps her feel like part of a larger team of peers.

“I’m not Native,” Swanson says, “[so] to feel like I have a team that I feel comfortable calling and asking questions about the culture, now I have resources. The team has provided that, and if they don’t know an answer to my questions, they know where to go.”

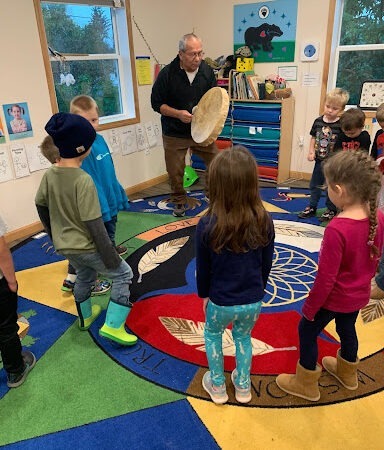

The kids at Little Eagles love it when Mr. Dowd (an elder and member of Wiikwedong’s Cultural Advisory Committee) visits their classrooms each week, and Swanson threads the cultural lessons throughout every day. “We have an Ojibwe cleanup song the kids naturally just sing now. They’re going home and instead of saying to their parents things like, ‘there’s a deer!’, they’ll use the Ojibwe word for deer: waawaaskeshii. It’s becoming part of who they are, and then the parents become curious.”

While everyone walks together on the healing path, the babies of Keweenaw Bay are leading. As Denomie says, “Their little brains have all that space to store all this memory. Their families are still going through what I went through. I know if they get their culture and identity returned back to them, they’ll be able to heal, thrive and grow.”

Comments