This post first appeared on Black Like Us.

Unforgiving sunrays relentlessly beamed down on sharecroppers as they worked the fields of the Mississippi Delta. Covered by the shade of their hats, and the clothes on their backs to shield them from the sun, sharecroppers worked to harvest cotton. Only now, they would receive pay for working in the fields as slavery was no more, but cotton was still a lucrative crop.

Like other children in the Mississippi Delta, 5-year-old Okolo Rashid went out into the fields with her father, mother, and siblings.

Her little brown hands would grasp the plants, picking them from the top of the stalk to the bottom to pull the cotton out of the bur. With each addition to her family’s harvest, there would be hope for a life of stability, but the system wasn’t designed that way.

Rashid’s family was falling into a cycle of indebtedness, as sharecropping wasn’t meant for them to get ahead in life. Instead, it was a system that kept families reliant upon landowners.

“My father would eventually realize that it wasn’t going to work,” Rashid said. “We were living in rural Mississippi. He just didn’t understand the culture; he got us out of there, but we had to sneak (out) in the wee hours of the morning during that particular period of time. You couldn’t just up and leave.”

She was born in Mississippi and grew up during America’s tainted history of segregation and racial oppression. The South lacked opportunities, so her family remained as sharecroppers, even after they left the Delta for a better life.

“I was 5 years old at that time. We didn’t move to Jackson. We moved back to another part of rural Mississippi, and we continued to sharecrop,” Rashid stated. Her family eventually made their way to Jackson, which would become home.

“I was close to 10 when we moved from Flora to Jackson. But even when we moved here, we used to go back and work in the fields because we didn’t have opportunities for money,” she said. “So over the summer, we would still go back and work in fields.”

Though sharecropping would remain a primary source of income for her family, things changed for Rashid when she was 10 years old. That was the first time she was able to attend school extensively. Before moving to Jackson, a sharecropper’s schedule served as a school schedule for Rashid, which meant attending school only after the harvest season, that’s half a school year.

“When we moved to Jackson, I started school in the fourth grade, and I never missed a day,” Rashid recalled. “Even when I was sick, I got up and went to school each day. I didn’t understand why I was doing it until later on. Until I became more knowledgeable about human makeup. I was discovering myself. There is something that God puts into every human being. We call it inner dignity. It’s motivation that’s naturally deposited in a human being toward excellence.”

Years of minor education and exposure didn’t deter Rashid’s yearning to learn. Her thirst for knowledge propelled her educational journey.

“In the beginning, I could barely read, and I say barely, I don’t even know if I could read,” Rashid said. “We didn’t have a book in the house when we were living in Flora. I said, a house without a book except the Bible. We never read it, but it was there, and the fact that I was able to graduate with honors. So it’s like applying yourself. And so some people are more… in tune with that.”

Rashid graduated high school and started her college journey at Hinds Community College, formerly Hinds Junior College, where she graduated with a degree in secretarial science administration in 1970. She was one of a hand full of Black students who helped integrate the college. She continued her education at Tougaloo College and Jackson State University, earning degrees in economics, and public policy and administration.

“I went to work at Tougaloo College, and that’s when I decided to go back to school to get my bachelor’s,” she said. “And then from there, as soon as I got my bachelor’s, I went on and got my master’s in public policy and administration. And that gave me the grounding and gave me the expertise to for organizational development and practice more. It’s like I was already an activist.”

During her college years, she was immersed in both education and activism, where she aligned herself with civil rights workers, the Republic of New Africa, and Black nationalists like Stokley Carmichael.

“It’s like you had that sense of freedom. I (was) motivated from when I was a child and continued to go to school,” she said. “It’s like always putting myself in the environment, always showing up. If you show up, you show up, and then you show up prepared. That’s something that’s already in the human being’s makeup. And so those things were able to ground me and propelled me… [College] gave me the theory that I needed… I just continued to build on it. My whole life has just been building on those foundations that I’ve laid out for myself or established for myself. I just kept building on them.”

Building community through activism, education, and religion

In December 2000, Okolo and co-founding partner, Emad Al Turk, along with their spouses, and a group of Jackson Muslims founded America’s first Muslim Museum focused on educating the public about Islamic history, art, and culture.

Fast forward to today, Rashid, as co-founder of the International Museum of Muslim Cultures in Jackson, where her passion for activism, education and religion culminated under one space, after she and Al-Turk, along with a passionate team, worked to gain support for the museum in Mississippi.

The International Museum of Muslim Cultures debuted in 2001 with its exhibition, Islamic Moorish Spain: It’s Legacy to Europe and the West, as a companion to the Mississippi Commission for International Cultural Exchange’s premiere of The Majesty of Spain: Royal Collections from the Museo del Prado and Patrimonio Nacional, which attracted over six-hundred thousand visitors; while IMMC’s exhibit focused on Muslim culture and history captured thousands. The museum now includes the exhibits: Legacy of Timbuktu Wonders of the Written Word and Muslims with Christians & Jews Covenants & Coexistence.

The exhibitions align with Rashid’s goals to help educate and raise awareness about Muslim culture and history. When Rashid and her husband, Sababu, became Muslim in 1975, she said they started working to bring communities together.

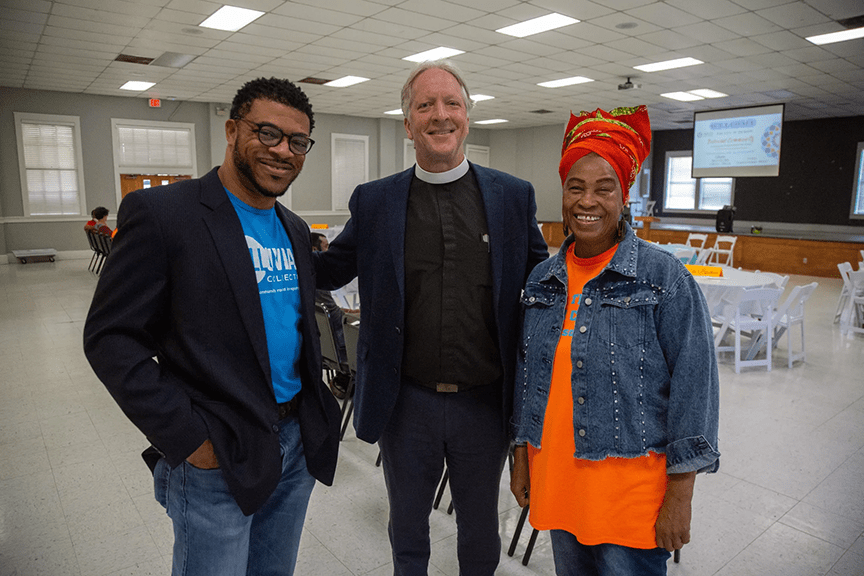

Photos courtesy of Okolo Rashid.

“We decided to look for an ideology that gave us the moral base as well as it also strengthened, promoted and advocated for freedom, justice, and equality,” Rashid said of their decision to become Muslim. “And so that’s what led us to embrace Islam in early years.”

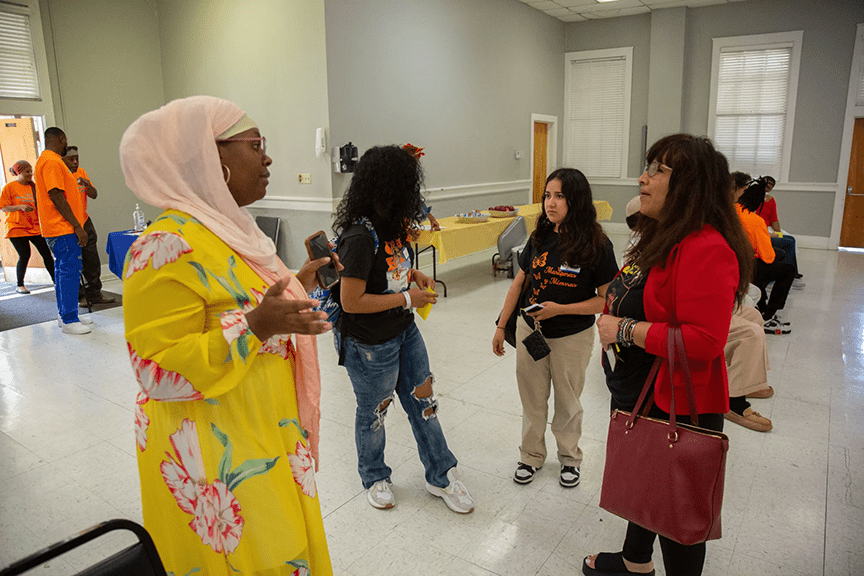

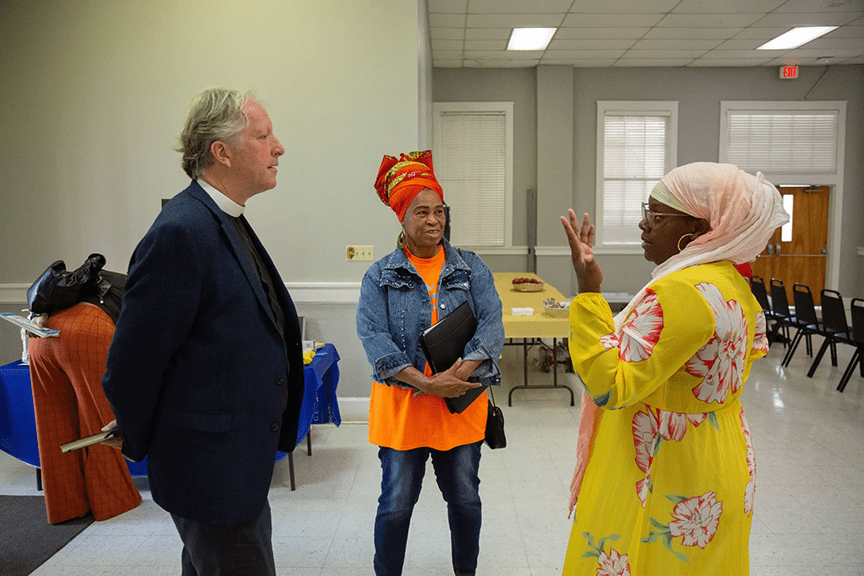

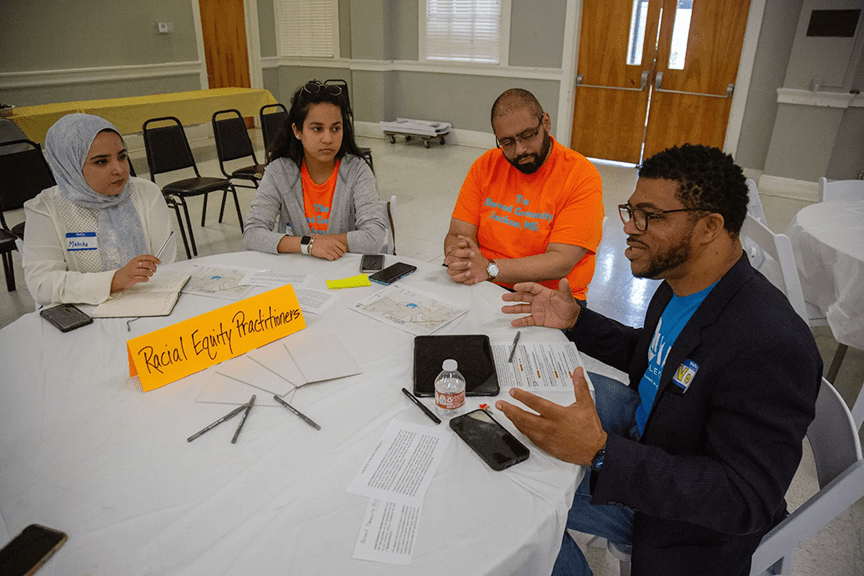

Most of their work has been a continuation of civil rights and equity. Rashid is working to engage residents in civic and community conversations to build an equitable Mississippi through what she calls the “Beloved Community.”

“This idea of connecting yourself to your creator and having a sense of self-determination, all these things that I talked about earlier… I came to embrace this idea of the Beloved Community. The only way we are going to accomplish the Beloved Community is that we’ve got to rethink the Civil Rights Movement and the African-American Muslim movement as parallel movements to one freedom struggle.”

The program, which is still in the pilot phase, is inspired by the teachings and philosophies of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Imam W. Deen Mohammed (transformative leader and reformer of the Nation of Islam), Medgar Evers, Fannie Lou Hamer, Jackson’s Mayor Chokwe Lumumba Sr., and the Mississippi Freedom Movement.

Rashid’s vision of the museum mirrors the statement on the nonprofit’s website.

“Our vision is to be a multifaceted institution that presents Muslim perspectives through the influence of Islamic civilization and its contributions to the world,” the website reads. “Our mission is to be America’s first Museum dedicated to educating the American Public about Muslim history, art and culture.”

Since its launch, thousands of people have been exposed to exhibits featuring Muslim history, art, and culture. The venue has also gained support from political and community leaders and private foundations like the W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

Rashid remains humble, yet grateful for what she and others have been able to accomplish for the Muslim community.

“It’s amazing,” she said of their accomplishments. “But everything that we’ve done, it’s just been building on the foundation that we’ve already laid. I’m just a sharecropper’s daughter.”

For more information about the International Museum of Muslim Cultures or their exhibits, visit their website here.

They can also be reached by calling (601) 960-0440 or email [email protected].

Comments