A little, indigo fruit sparks a successful program

Brandon Seng wanted to find solutions to end hunger and obesity in his home region of Northern Michigan. But he didn’t know a blueberry would take his journey on a new and unexpected path.

Seng had started a small nonprofit in Manistee County, focused on creating more healthful, locally-sourced school lunches. During an after-school cooking club, where he taught kids about preparing nutritious food, a student told him that she had never eaten a blueberry because her family couldn’t afford it. This was in Michigan, the nation’s largest blueberry producer.

“We don’t recreate the wheel in our program, we find out who has something available that might be un-utilized or under-utilized, and figure out how to leverage that as opportunity.”

“I was just instantly mad…I was mad because access to food is not a luxury, but a right,” Seng said. “They don’t have blueberries at the food pantry and we didn’t serve blueberries at school, so she didn’t eat blueberries.”

Seng decided to correct what he saw as a clear injustice. That day he connected with a local farmer and started freezing 200 pounds of berries in a small blast freezer to be served in the school’s cafeteria.

From one fruit to many

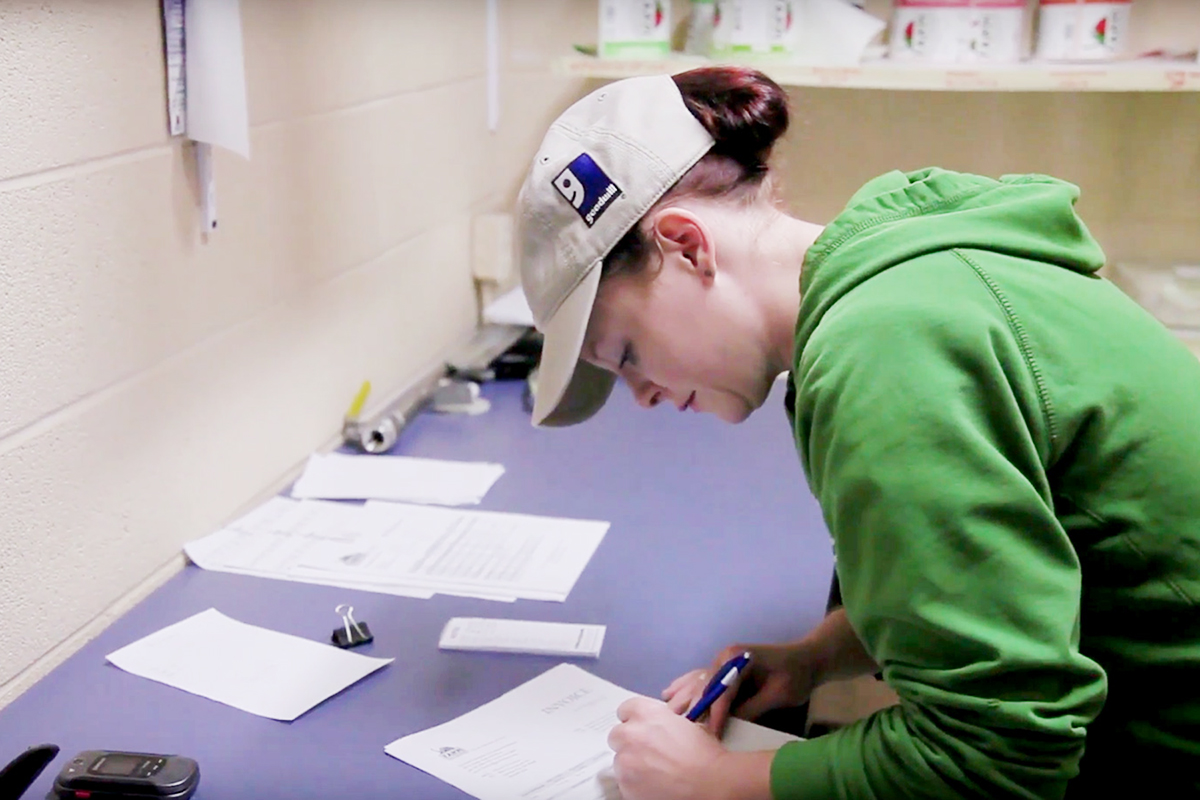

After that initial batch of blueberries frozen in 2011, Seng started processing asparagus, cauliflower, peppers and strawberries. Many people within the community pitched in to help grow the small project into a full-fledged program – Seng says it was that support that really helped make it a rapid success. Eventually the program integrated with Goodwill Industries of Northern Michigan as Farm to Freezer. Today, it is primarily a job training program, but its products are being served in 12 school districts and more than 50 schools, as well as in senior centers and through Goodwill’s Meals on Wheels program.

Working with local and regional growers, Farm to Freezer purchases fruits and vegetables that can’t be typically sold in stores – though they’re perfectly edible. The produce is flash frozen to be enjoyed during the winter months, ensuring kids get fruits and veggies year-round.

Today, Farm to Freezer is freezing kohlrabi fries and Romanesco (or as students now know it, “space broccoli”), and getting picky elementary kids excited about kale chips.

“Parents call me at home and say, ‘Annabelle had a vegetable at school today and she can’t tell me what it was but it was potato chip that looked like grass,’” Seng said.

A triple win

“It’s a win for individuals who need a fresh start reentering the workforce, it’s a win for local farmers who have a market now for additional products, it’s a win for hungry families in our community because now we have nutrient-dense products available year-round.”

Farm to Freezer is getting more children healthful food, supporting local food producers and providing job training to those most often marginalized – people with disabilities, recovering from addiction, transitioning from homelessness, and reentering society after incarceration. Seng calls it a “triple win.”

The program has so far graduated 50 trainees and plans to get another 20 people job-ready over the next year. Many of the graduates go on to work with one of the 25 local farms or three food processors partnered with Farm to Freezer. Providing job training can help build family economic security, setting parents on a career path so they can provide their children with a better life.

Offering a fresh start for families

One graduate – Trish – arrived at a career fair “pulling her young son on a sled,” where she met Seng and the Farm to Freezer team.

“We look for individuals in our program that are motivated … and I haven’t seen motivation like that often,” Seng said. “She was just a person that needed a place to get started and I knew then that we would be a piece of that story.”

Trish is now a full-time sales employee with Farm to Freezer. She’s been able to afford her own apartment and car, so she’ll no longer need to pull her son along on a sled in the middle of winter.

“She was someone who had been turned away from other jobs … and is now a cornerstone of our movement. Where she goes next is really going to be her choice,” Seng said.

“Choice breeds dignity, and dignity breeds respect and that respect is what we want in our community.”

Key Lessons

Assess community need and capacity.

“What resources currently exist within the community that you serve or want to serve? And then figure out a way to connect those resources. We don’t recreate the wheel in our program, we find out who has something available that might be un-utilized or under-utilized, and figure out how to leverage that as opportunity.”

Ask for help.

“We’re not, by no means, the leading experts in fruit and vegetable processing – and we’re very clear about that – in our program we ask for help, we ask for support, we ask for guidance. I think that being humble enough to say, ‘Hey, we don’t know it all.’”

Be willing to go to Plan B.

“There are products we have tried and will never do again … The outcome needs to be first and foremost, and how it happens can’t be written in stone, it needs to be in pencil.”

Comments