With a nationally recognized early childhood system through its Smart Start public-private partnership, North Carolina provides fertile ground for developing a robust farm to early care and education initiative. Farm to early care and education enhances the health and education of young children by creating systems and experiential learning opportunities that connect children and their families with local farmers and by procuring locally sourced food.

The W.K. Kellogg Foundation provided five years of funding to bolster North Carolina’s efforts and build a coalition across child care, education, farming and agriculture, and public health sectors to ensure young children have equitable access to healthy food and quality early learning.

Today, the North Carolina Farm to Early Care and Education Initiative at the Center for Environmental Farming Systems (CEFS) is an umbrella for a diverse set of partners to link early care and education centers and local farmers. Together, they are building a community-based equitable food system that nourishes kids and families.

Improving community access to nutritious foods

Child care educators across North Carolina tell Caroline Stover, the project director for the initiative, that if the children aren’t getting healthy foods in the classroom, “then they just aren’t getting fruits and vegetables on a regular basis.” The initiative makes it possible for child care centers, Head Start programs and family day care homes to provide nutritious local foods, which families may not have access to in their neighborhoods, in meals and snacks.

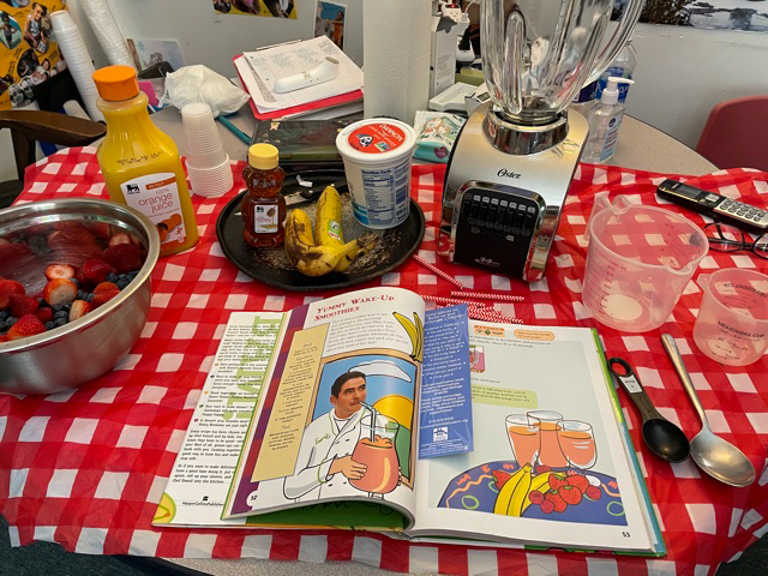

By eating farm-fresh foods at an early age when children’s tastes are forming, they develop positive relationships with food and lifelong healthy eating preferences. Data show that children who eat homegrown fruits and vegetables are 2.3 times more likely to eat the USDA-recommended five daily servings.1 Through farm to early care and education, young children engage in growing gardens, preparing healthy meals, visiting local farmers’ markets and more.

Teneshia Tyson, director and owner of Follow the Son Child Care Center in Greenville, North Carolina, shares one of the farm to early care and education activities she’s been most proud of: a farmers’ pop-up market inside her center. “This whole experience has been a big deal, not only for kids but for the staff, me and parents too.”

Seeing local media coverage about the center’s pop-up market, a woman with the Washington Waterfront Underground Railroad Museum reached out to come talk with the kids about how enslaved people used the crops they were growing on their journeys to freedom. “She brought watermelons and showed how people used them to cook chicken,” says Teneshia. The woman also described how enslaved people saw sunflowers as clues to needing to lay low or turnips as signs that someone was going to “turn up soon” to help them to the next destination.

Watch how the children, families and staff at Follow the Son Child Care Center are benefiting from farm to early care and education.

Farm-fresh foods engage families too

“Farm to early care and education is a natural extension into the community,” says Caroline. Families who volunteer in child care center gardens are often able to take fruits and vegetables, plants and seeds home to extend learning. This kind of community engagement is vital to successful farm to early care and education programs, ensuring access to healthy foods at home.

At Follow the Son, parents can use food stamps at their pop-up market. “A lot of parents leave with a bag full of collards, tomatoes and cucumbers,” says Teneshia. “It gives parents the opportunity to try things they might not normally buy themselves in the grocery store.” The center also provides recipe cards for families to easily and quickly prepare foods at home.

A pathway for racial equity

Food is a natural vehicle for racial equity and inclusion work. By connecting local farmers with child care centers, we can “change the narrative about who grows food and who eats healthy foods … and open up those stories to be more inclusive,” Caroline says.

The North Carolina Farm to Early Care and Education Initiative adopted a racial equity framework to guide its work. Racial equity is also a key focus of trainings for early care and education providers. “We talk about what racial equity means in our local food system, for our children and for the populations that these teachers and directors are servicing,” says Shironda Brown, the training program coordinator for the initiative.

“When you really get into it, it’s about racial equity. … It’s about growing the community. We want families to be able to grow and share food and these areas that were food insecure to not be anymore.”

Shironda Brown, training program coordinator for the North Carolina Farm to Early Care and Education Initiative

Shironda also helps teachers understand how to connect children and families more meaningfully to their food: “When you really get into it, it’s about racial equity. … It’s about growing the community. We want families to be able to grow and share food and these areas that were food insecure to not be anymore.”

She sees farm to early care and education as critical to turning the tide in restoring thriving farmlands and supporting nutrition security in communities of color. This is done, Shironda says, “By getting back to having local farmers and having child care centers and connecting them, so children and their families understand this is a viable way of life and respect what farmers and those that work the land do.” Focusing on children living in food insecure areas and connecting them with farmers of color helps encourage a new generation of food producers.

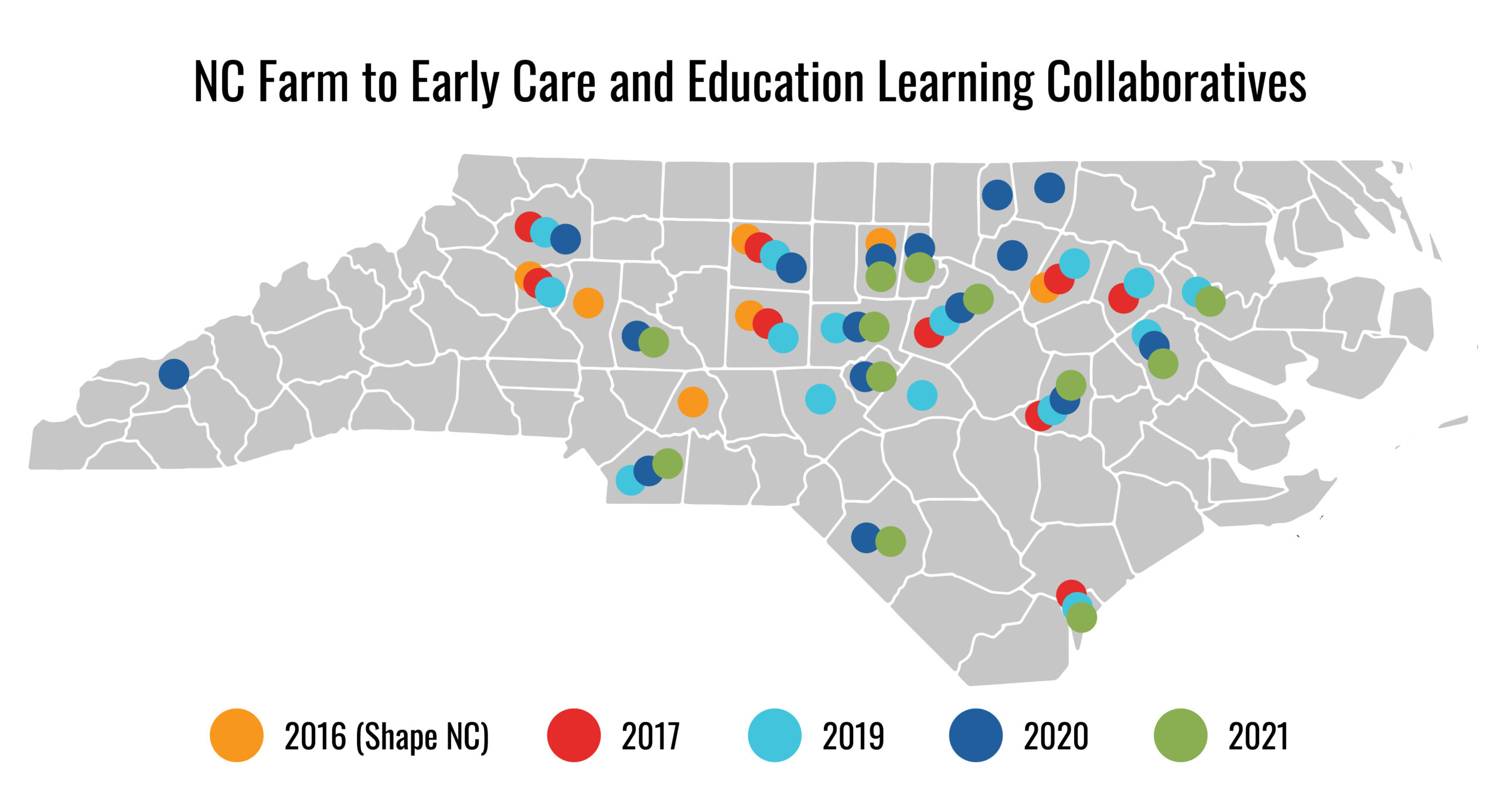

Learning collaboratives connect communities

North Carolina was one of the first states to organize local learning collaboratives – community-based teams that link child care center directors, teachers and cooks with early care and education technical assistance providers and agriculture representatives to advance farm to early care and education.

The initiative tapped into the existing network of county Smart Start partnerships and Head Starts to provide centers with farm to early care and education technical assistance. They work with centers to improve quality of care by integrating farm to early care and education, while also meeting and exceeding state quality learning standards.

On the agriculture side, the initiative connects local food hubs, nonprofit organizations representing farmers and NC State Extension agents with centers. “We have family and consumer sciences extension agents cooking with children in classrooms. We have horticulture extension agents helping children grow gardens and teaching them about soil,” Shironda says.

“We start with a collaborative approach and bring everyone together,” Shironda continues. Cross-sector teams meet together from across the state for a series of learning sessions facilitated by CEFS. The first session overviews farm to early care and education, emphasizing racial equity. The second session focuses on goal setting and detailing the model of plan, do, study, act, also known as PDSA, so providers understand how to develop and execute action plans for farm to early care and education specific to their communities.

Sustainability is the focus of the third session, allowing providers time to plan how their farm to early care and education programs will continue past the collaborative. “How do they continue with families, how do they continue to engage communities, so people know gardens are here,” Shironda says.

In between these sessions, team members engage in regular webinars and meetings to share best practices, problem solve and advance their action plans. Affinity groups organized around roles, such as center director or cook, also connect people across the state. The 2019 collaborative included 23 centers and 150 participants from 15 counties.

Collaboration in food procurement

While the benefits of healthy eating and locally sourced foods are undeniable, procuring local foods can be a barrier for early care and education centers. Farm-fresh foods can cost more for centers to buy and can take more effort to prepare than processed foods. Individual deliveries and classroom visits can be time-consuming for farmers, while the associated profit margins can be slim.

The initiative is exploring different models to make local food procurement easier on centers and financially viable to farmers. Examples include combining purchasing with K-12 school districts, networking family child care centers to aggregate demand and have more purchasing power, and offering community supported agriculture (CSA) boxes at child care centers so that farmers can benefit from larger order volumes.

“CSA boxes are delivered to the center so families can pick up the food box at the same time as their children. Also, the centers have the same boxes for snacks and meals that week,” says Caroline. “We love that because the recipes they’re making at school can be sent home with the families.”

CEFS has also created local procurement resources, such as a local food purchasing guide and a tip sheet for talking with grocery store managers about sourcing local food.

Central kitchens are encouraging solutions

Child care centers are not networked in the same way as K-12 school districts, which can order in large volumes and deliver in one spot. “It’s a really decentralized system; there are issues around food delivery, around volume,” explains Dara Bloom, associate professor and local foods extension specialist at North Carolina State University and assistant director of community-based food systems for CEFS. “Centers can feel intimidated by the process of ordering, bringing in and preparing local foods.”

To address these issues, CEFS is partnering with Child Care Services Association, which has central kitchens in Chapel Hill, Durham and Raleigh. They prepare meals using local, farm-fresh ingredients and deliver to about a dozen centers from each kitchen. “The higher volume of purchase makes it more of a market for local farmers,” says Dara. “It also shifts some of the burdens off child care centers with shopping, menu development, meal preparation and CACFP [Child and Adult Care Food Program] paperwork.”

Together with UNC’s Children’s Healthy Weight Research Group, the Duke Sanford World Food Policy Center, The Conservation Fund’s Resourceful Communities and Solid Rock Ministries in Harnett County, CEFS is implementing and evaluating what it takes to start a central kitchen in a rural area. With funding from the Duke Endowment, the Solid Rock United Methodist Church is renovating its kitchen to serve about 400 children through 10 child care centers. While the pandemic has slowed down the project, the church is hoping to recruit child care center partners in spring 2022.

Focused on the future

All of these collaborative efforts are adding up to improved quality early learning for children and increased access to healthy food for families and communities. They’ve had success because of North Carolina’s community-based, cross-sector approach.

Shironda says the local community wants this program to succeed because:

"We’re dealing with the children of today who are going to be taking care of our world tomorrow.”

Lessons Learned

Early care and education providers are responsible for an overwhelming number of activities that can extend past the time when children go home. While they’re expected to wear a myriad hats, they typically earn below living wages. Ensuring they’re paid a livable wage creates stability – for them, for centers and for the children with whom they develop relationships. Having the financial resources to support farm to early care and education is also essential – from the purchase and preparation of fresh, healthy foods to professional development opportunities. An investment in providers is an investment in the health of our children.

A key ingredient of North Carolina’s farm to early care and education success is the community-based approach and cross-sector connections that happen through the learning collaboratives. The collaboratives link local people in early care and education, health, agriculture and farming to develop holistic solutions that enrich early learning environments; improve community nutrition; and build sustainable local food systems. “We come from a whole approach. It’s about these children, but it’s also about the community that houses these children,” Shironda says.

Procuring locally sourced foods can be challenging for early care and education providers, especially smaller centers and family home child cares with limited resources. Similarly, local farmers face obstacles in getting their foods to markets. Figuring out food procurement solutions that work both for providers and for small farmers has multiple benefits. For example, as Dara says, “The centralized kitchen is really a win-win with bigger orders for farmers and taking burdens off child care centers.”

The W.K. Kellogg Foundation is culminating a five-year, five-state pilot for farm to early care and education to support healthy children and equitable, sustainable food systems. This story was made possible by interviews with the Center for Environmental Farming Systems and Follow the Son Child Care Center.

Explore More About Farm to Early Care and Education

Across the country, providers, local farmers, community organizations, state agencies and other partners are coming together to develop successful farm to early care and education programs.

Comments