In America’s centuries-long struggle with racism, a high-profile inflection point is neither the beginning nor the end of the story. So is the case with the murder of George Floyd and the uprising that flowed into Minneapolis’ streets in the days that followed.

The neighborhood surrounding these events is home to one of the largest urban American Indian communities in the United States. Over the past 45 years, Native-led MIGIZI has created a hub for youth empowerment in the neighborhood, where youth and community members also navigate the day-to-day realities of racism. After losing their newly-designed organizational center during the unrest of 2020, MIGIZI staff found themselves holding space for complex emotions and longstanding community trauma.

Editor’s Note: In October 2023, MIGIZI officially opened their brand-new building with prayers, messages from staff and board members, and their host drum and jingle dress dancers.

"There’s a reason all of this happened in our community. We have some of the greatest racial disparities in the country. If we’re not invested in changing that, our young people will not be able to have what they deserve.”

Kelly Drummer, president, MIGIZI

"The need to support Black and Brown people doesn’t go away just because you’re no longer seeing our community members murdered on TV. It’s constant, and we all need each other to get to a better place.”

Mishaila Bowman, marketing & communications manager, MIGIZI

MIGIZI, Bald Eagle

MIGIZI means bald eagle in the Ojibwe language. In 1977, Laura Waterman Wittstock and Roger Buffalohead chose this name for their youth media program, because the bald eagle is a communicator and guardian who demonstrates high standards. For the past 45 years, MIGIZI has ensured that American Indian youth living in and around Minneapolis are honored for their sacred gifts and boundless potential, and empowered to share these gifts, as leaders, with their communities and nations.

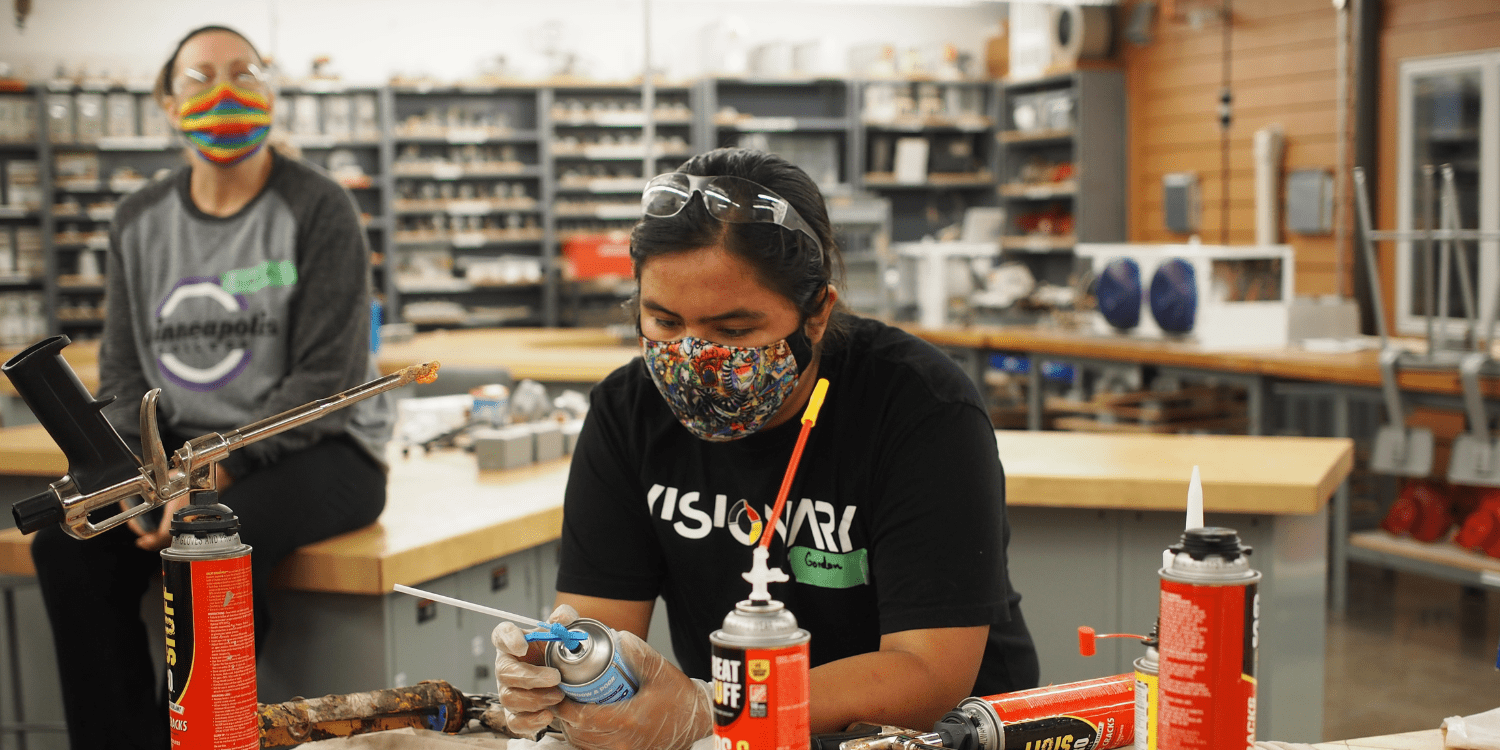

Over the years, MIGIZI has served more than 9,000 youth directly, evolving their programs as technology advanced. They began by producing radio programming, with American Indian news reaching homes across the country; they then moved into graphic design, filmmaking, podcasting and social media marketing. Now they offer programs in green technology and STEM, along with academic support, all with an eye toward assisting Native youth to graduate from high school, enter post-secondary education and find their career paths.

“All along,” says President Kelly Drummer, “MIGIZI has been a champion for American Indian education in public schools. That’s one of our trademarks.” MIGIZI and the Metropolitan Urban Indian Directors Group maintain a memorandum of agreement (MOA) with the Minneapolis Public Schools to offer a culturally-relevant academic curriculum. The Dakota and Ojibwe languages are taught in some local schools. The Anishinaabe Academy was established for the K-5 level. A handful of local high schools offer American Indian Pathways, and there’s an All Nations program at South High School, located near MIGIZI.

In July 2019, the MIGIZI youth and their mentors moved into a building especially designed for their media and STEM programming. The new program home was located near Lake Street, in the heart of Minneapolis’ American Indian community. Students helped design everything, from the size of each room to selecting paint colors and floor tile, assisted by architect Samuel Olbekson, also a MIGIZI alumnae.

Lead media instructor, Binesikwe Means, says the building project was more than a redesign exercise for the youth. “A lot of students are told because they’re low income they shouldn’t have nice things,” Means says. “It was exciting to see our students take ownership, really take care of the building, and feel like they have a home.”

Eight months after they moved in, programming went virtual with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

A few weeks after that, George Floyd was murdered approximately two miles away.

The unrest that followed focused heavily on Minneapolis’ 3rd precinct police station – only a few doors down from MIGIZI’s brand-new home. During one of the nights of unrest, as protests turned to flame, sparks spread through the rooftops and reached the MIGIZI building.

Drummer watched it burn.

MIGIZI’s Guardians

“I’m a very spiritual person,” Drummer says. “I saw both the evil and the good and it was very powerful. The first couple nights [of protest] were peaceful. The day before the fire everything else was broken into and our building was perfect. But you could feel the escalation.”

Drummer started receiving phone calls from community elders that final day, encouraging her to remove significant items from the building. Most important were audio archives dating back to 1976 that contained MIGIZI’s American Indian news programs.

“I didn’t want to panic,” Drummer recalls, “but I called the American Indian Movement (AIM) and they came to protect the building. That night, everything was on fire. They were saying gas might explode. AIM said everyone should leave. Everyone did, except my husband, daughter and me. They [the crowd] burned the post office, then the building next door and then our roof caught fire.”

The flames that engulfed MIGIZI had been gathering for decades in Minnesota, a state where an average of one person per month has been killed by police since the year 2000. Metaphorically, the fire didn’t start the week of the unrest.

“Our community had dealt with the 3rd precinct since the ‘70s,” says Means. “You hear so many reports of police officers putting Indian men in the trunks of their cars. In fact, it was a longstanding joke that the only way to get into the precinct was in the trunk. That’s why AIM was established here, the AIM patrol, because our people were being harassed, essentially violated by the police. The uprising had been brewing for a long time and it boiled over.”

National viewers didn’t see the whole story on the news that week. As was the case in many communities, competing agendas and ideologies converged on the streets, from people seeking greater social justice and an end to police brutality to those espousing white supremacy and others wanting to exploit the situation to destablize systems.

Drummer says confusion and conflicting emotions were evident in real-time. She remembers one young man wearing an anarchy symbol on his jacket knelt down and apologized to her as the building burned.

“I heard this from a lot of people: ‘why did you burn down your own community?’” reports Means. “The one thing I want people to know is those who have been prosecuted (for arson) are not from Minneapolis. People from outside came in looking for an opportunity to wreak havoc. And then they got to go home.”

For a year afterward, recalls Means, those who call Lake Street home had no grocery stores, convenience stores, gas stations or ATMs. Families carpooled to the suburbs to get their essentials. “As a community, we wouldn’t do that to ourselves, we wouldn’t do that to our elders” she says.

MIGIZI’s High Standards

The morning after the fire, while smoke hovered, MIGIZI’s community held a healing and prayer circle just outside the building. “They wouldn’t allow us too close to the building, because they were trying to figure out if power and gas were on,” Means recalls.

She says many MIGIZI youth came out, which refocused the staff. “They cried and laughed with us. It gave us a connection back to our youth and how we needed to be there for them. We had all just experienced something unlike anything we’d been a part of before.”

In the days that followed, MIGIZI staff and community members created medicine boxes with the help of the Dakota-led Wakan Tipi Center. They distributed the medicine to more than 150 youth. MIGIZI also organized a healing and unity event, re-committing to strength and resilience in the days to come. Other Native-led organizations in the neighborhood opened their doors for MIGIZI to host arts-based healing groups for youth, and to move forward with their summer training program. In the wake of the tragedy, MIGIZI still employed thirty youth interns that summer. WKKF was among the organizations supporting MIGIZI during this transitional time.

“That summer was what I needed to move on,” says Drummer. “After the fire, I felt like I was done. Elders told me not to look back, it’s all about how to move forward.”

Mishaila Bowman worked at Wakan Tipi at the time but says MIGIZI’s stance in the midst of grief led her to want to join their team. She is now MIGIZI’s marketing and communications manager.

“MIGIZI’s space was so much more than a building. It was a safe home and a space of healing for all youth. It’s not about the bricks, but what the building provided,” Bowman observes. “MIGIZI did a wonderful job of holding the feelings of trauma and grief over the loss of the building, but remaining steadfast in our values as Native people of protection of our community and holding space for everyone who witnesses blatant racism constantly.”

Moving Forward

MIGIZI will move into a new building again in late summer of 2023, thanks to an outpouring of support from philanthropy and the corporate sector. But, MIGIZI’s staff want everyone to know the work toward healing and justice is not episodic, it’s ongoing. They’re working with the hundreds of other businesses along Lake Street affected by arson and vandalism during the summer of 2020 and continuing to focus on ensuring Native youth can succeed in high school, college and beyond.

“It’s not over,” says Bowman. “So often when an atrocity such as the murder of George Floyd happens, we think it’s over just because it’s not in the news. The need to support Black and Brown people doesn’t go away just because you’re not seeing our community members murdered on TV.”

“There’s so much work to do collaboratively to restore our community and have a healthy community,” says Drummer. “MIGIZI can continue working on that, but we need long term investment.”

Comments