This post is also available in: Español (Spanish) Kreyòl (Haitian Creole)

The current pandemic has exposed many cracks in the U.S. public health system including the stark racial inequities and structural racism that are part of health care in America. Black, Brown and Indigenous people continue to die from COVID-19 at twice the rate of White people, and White people are getting vaccinated at a rate of two to three times more than people of color. While recent national trends suggest a narrowing of racial gaps in vaccinations, particularly for Hispanic people, disparities persist. Many factors—implicit and explicit—in the public health system have exacerbated inequities during the COVID-19 crisis.

“The coronavirus did not create racial inequities in health. It has just uncovered and revealed them. These disparities have long existed in the U.S., and persist across leading causes of death, from the cradle to the grave.”

Dr. David Williams, professor, Harvard University T.H. Chan School of Public Health

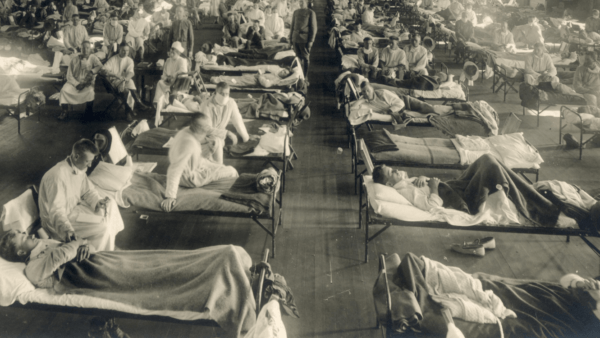

Learning from the past

The beginning of the largest mass vaccination campaign in U.S. history was marked by confusion. While federal health experts endorsed recommendations for vaccine prioritization, much of the responsibility for distribution was pushed to state health departments. An analysis of early state distribution plans showed that just over half (25 of 47) of the states with publicly available vaccine distribution plans had at least one mention of incorporating racial equity into their considerations for targeting of priority populations. And yet, people of color are more likely—at disproportionate rates—to be essential workers and to have high-risk underlying health conditions. Additional access points for vaccination have now been activated by the federal government, including distribution through retail pharmacies and community health centers, which have important reach into communities.

Perceptions about communities of color

Amid these structural barriers, there exist harmful perceptions that people of color – especially Black communities—do not want to be vaccinated, and that they as one homogenous group are being labeled as vaccine hesitant. While Black and Hispanic adults remain somewhat more likely than White adults to say they want to “wait and see” before getting vaccinated, enthusiasm for getting the COVID-19 vaccine has continued to inch upward across racial and ethnic groups. About six in ten Black (59%) adults and two-thirds of Hispanic (64%) and White (66%) adults now say they’ve either gotten at least one dose of the vaccine or will get it as soon as they can.

Barriers to access

Even though many people want to get vaccinated, historical, systemic barriers to health care access exist, especially for communities of color. Barriers include the ability to access and navigate online scheduling systems; an inability to take time off from work, especially when current vaccine protocols require two visits; an inability to take more time off from work to recover from vaccine side effects; limited child care options as parents navigate hybrid school situations; limited transportation options; and potential language barriers.

Read More

Check out how local health leaders in Detroit, Mich., Biloxi, Miss. and in Native communities of New Mexico were creative in removing barriers, building trust to address misinformation and helping people navigate the systems where they live in their languages, to make vaccines accessible and promote health equity in their communities.

Meanwhile, the relationship between communities of color and the public health system is complex and nuanced. Some scholars have even pointed to trust of inequitable systems that have historically excluded populations of color.

“We talk about Black communities being hesitant, but I think they have a healthy level of skepticism of a system that has treated them poorly historically up until the present-day moment,” said Melody Goodman, the associate dean for research and an associate professor of biostatistics at the NYU School of Global Public Health who studies health disparities.”

Learning from the past

Our recently published Reflecting on the past to transform the future: Lessons learned from grantmaking in promoting health equity and responding to crisis, which highlights WKKF’s longtime work with communities, experiences in emergency grantmaking and partnership with researchers and advocates, offers key lessons to address health and social inequities. An equitable crisis recovery response must:

- Be done in partnership with and at the pace of the people most impacted.

- Be supported by trauma-informed approaches—they are vital to long-term recovery and resilience.

- Strengthen the capacity of the nonprofits responsible for building the capacity of the community.

- Be grounded in an understanding that long-term problems require long-term solutions and investments.

Meeting the needs of the community

Post-pandemic, WKKF grantees, communities and partner organizations will re-imagine and rebuild systems centered on racial equity. They have the leadership, knowledge and resolve to advance their communities.

To date, WKKF has invested more than $15 million in organizations working to disrupt systems and racial inequities to ensure that vaccine equity promotes health equity. Our support has included backing front-line, community-based organizations who have been stretched beyond capacity during the pandemic; addressing national communication and campaign gaps by democratizing information; and convening partners in the philanthropic sector for collective community-based action.

“Enacting an equitable COVID-19 vaccination campaign is not solely about ensuring access to the vaccine for all,” said Alexandra Quinn, CEO of WKKF grantee Health Leads. “Too often, top-down public health interventions leave those most requiring of health support feeling alienated from design and decision-making processes.

"Too often, top-down public health interventions leave those most requiring of health support feeling alienated from design and decision-making processes."

Alexandra Quinn, CEO of Health Leads Tweet

For Black, Latino/a and Native communities that have too often been the subjects of medical experimentation, unwanted or coerced medical treatment, or have had their voices ignored in decision-making processes around public and community health, an equitable COVID-19 vaccination campaign, one that is driven by and invests in local community-based organizations and community-based workforces (like community health workers and Promotoras de Salud), could begin to reckon with the damage wrought both by these histories and the pandemic response.”

Comments