Editor’s Note: Wicoie Nandagikendan re-opened their Dakota language classroom in Fall 2023.

In the Dakota language, Wicoie means words; in Ojibwe, Nandagikendan means learning. Wicoie Nandagikendan is a place for young children to learn the Dakota and Ojibwe languages in Minneapolis, the largest urban American Indian community in the country.

Since 2006, Wicoie Nandagikendan has trained over 50 teachers to provide classroom immersion in Dakota and Ojibwe. Their efforts laid the groundwork for seven more language immersion programs in Minnesota, and those they’ve trained now teach at the K-12 and post-secondary levels. Wicoie Nandagikendan’s staff see the far-reaching effects of this decades-long effort.

Director Jewell Arcoren says,

“We know a lot of the kids who have benefited because they’re still in the community. Language offers a pathway to resilience, health and wellness. The kids roll into kindergarten and their identity is solid.”

Now, the school’s administrators and teachers are participating in the Indigenous Early Learning Collaborative, using community-based inquiry to envision an entire Indigenous early learning system.

Together with elders, parents, and supportive adults, the school’s administrators explored one primary question: “What does a whole, healthy Indigenous child look like, and how do we get them there?”

What surfaced was the need for space. “The community talked about all kinds of space,” says Fawn YoungBear-Tibbetts, Wicoie’s program director and Indigenous food coordinator. “Physical and metaphysical space, space for recovery, for health and wellness, for Indigenizing policy. Community members envision internal and external space for harvesting, ceremony, intergenerational language learning, food sovereignty, cooking, gardening, outdoor learning, la crosse and soccer fields.”

Though it’s difficult to imagine with the city’s brick storefronts and skyscrapers, Arcoren says, “There was originally space here for all these practices before colonization.”

Prior to colonization, Native peoples across North America built and sustained vibrant societies through sophisticated systems of governance, which they developed, adapted and refined during thousands of years of caring for and living on the land we now call North America. A succession of policies created by federal and state governments systematically took land from Indigenous Nations, a process that continues today.

Removing people from their land, along with federal laws that made Native ceremonies illegal, resulted in severed ties between Native people and their cultural ways of life, including traditional values and processes for raising and educating children. Similar to land back movements, which seek to return stolen land to Indigenous hands, Wicoie Nandagikendan’s community-led focus on creating space is an effort to restore Native communities to wholeness.

“Our own space will make us less invisible in our own community.”

Fawn YoungBear-Tibbetts

Currently, Wicoie Nandagikendan holds space for two classrooms (one Ojibwe, one Dakota) in another school’s building. However, the tuition required by the school proves cost prohibitive for Native parents.

“We talk about having to buy your land back. This is buying your language back,” Arcoren says, pointing out the irony of asking parents to pay for learning that, before colonization, would have naturally taken place in families and communities.

Based on the community’s expressed vision, Arcoren and YoungBear-Tibbetts are working on a model that would provide free or low-cost language education. What they discovered through the community-based inquiry process provides not only the vision but also all the data they need to invite support from collaborators and funding partners.

Land back has been a movement in Indigenous communities for generations, as Indigenous people continue to organize to get Indigenous lands back into the hands of Indigenous people. There have been many examples of Indigenous people and movements that have actively worked to dismantle the impact of colonization through the Land Back movement. Indigenous people are also reclaiming languages that were once forcibly disrupted by colonization – namely through federal Indian policy and the Federal Indian Boarding School system.

In Minneapolis, creating an Indigenous early learning system means starting from square one. Of Wicoie’s two classrooms, only the Ojibwe class is active. That’s because Dakota, Minnesota’s very first language, is critically endangered. School administrators joke that everyone in the state speaks broken Dakota – with the state’s name a derivative of the Dakota word mní sóta meaning clear blue water. However, only one person now living in the state spoke Dakota as their first language.

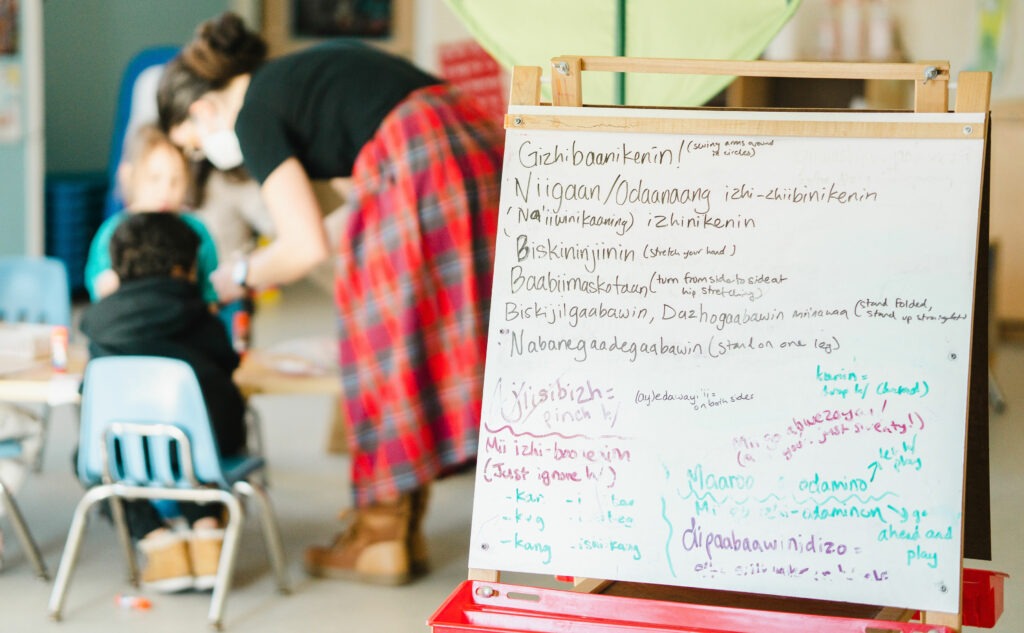

Opening more classrooms means training more teachers. Wicoie uses a master-apprentice model. Immersion teachers speak in the intended language throughout the school day, without relying on English at any time.

Liz Zinslie, the Ojibwe classroom teacher, describes the experience: “For adults, translation is like doing a hard math problem in your head,” while also responding to the moment-to-moment needs of young learners.

She apprenticed with Hope Flanagan, an Ojibwe speaker and early childhood educator. “The master-apprentice model sets people up for success. Learning in context was important. Hope modeled invaluable experience in how to teach in-language while also managing the classroom.”

As Wicoie Nandagikendan builds this early learning system, YoungBear-Tibbetts says, “We have a lot of jobs to fill. Our community can meet its needs given the right circumstances.”

The right circumstances include covering tuition and books for community members who want to become language immersion teachers; some community members have the language skills but not the early childhood education certifications needed. However, teachers’ lived experiences are equally important. “You have to be part of this community if you’re going to work in this field,” says YoungBear-Tibbetts, “and that means creating space for people who already have skills, but need training and certification to do this job with kids.”

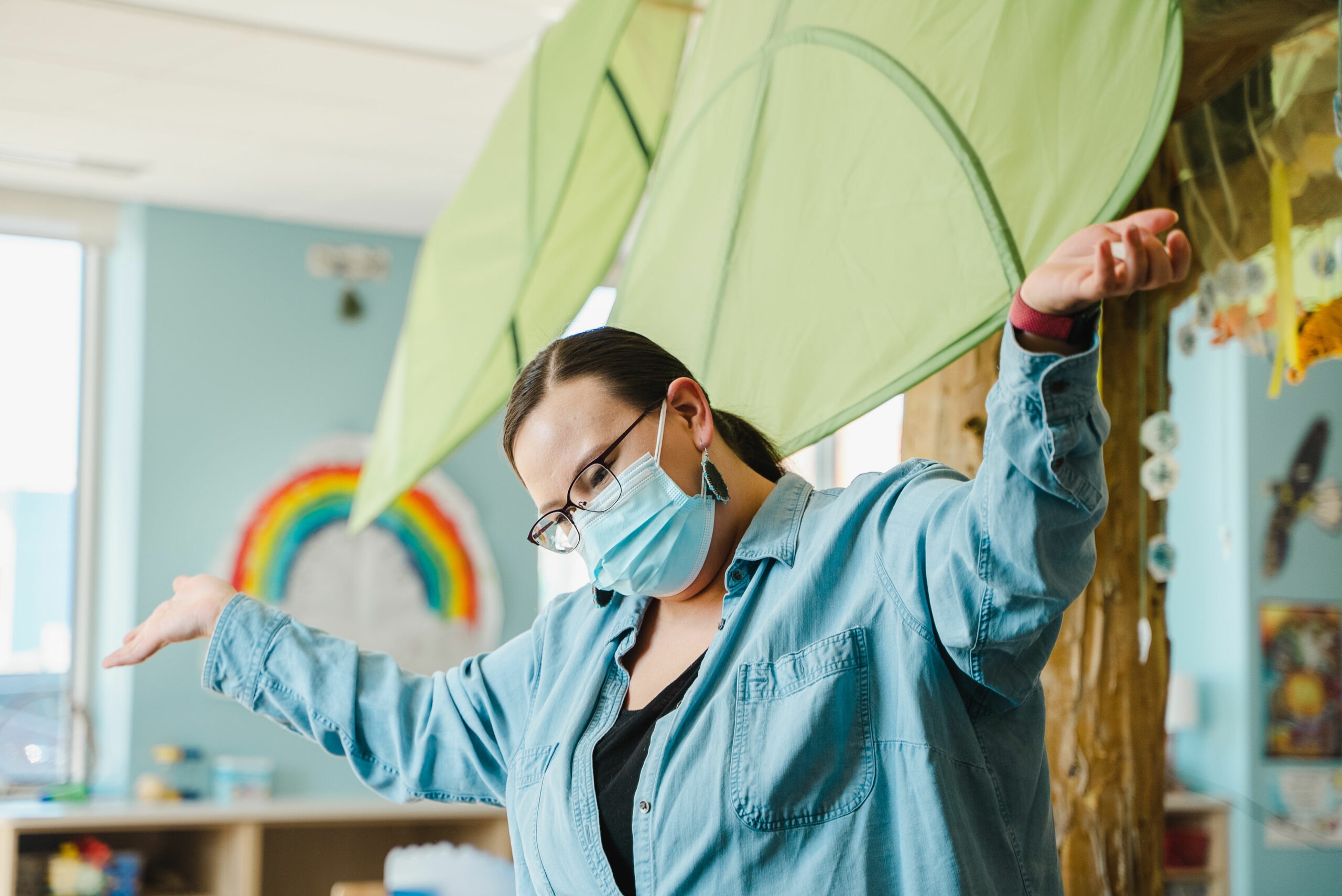

Waase Ficken co-teaches in the Ojibwe classroom. Her language journey began in high school, where she was able to take Ojibwe classes through all four years. When she got to college, she initially wanted to be a nurse or social worker. However, an undergraduate course in American Indian Studies changed her mind.

“Hearing about our traumatic experiences,” says Ficken, “our language, culture and identity all intentionally taken, inspired me to need culture, to need language, to fully know who I am. I knew that I wanted to teach my kids one day.”

Ficken gave birth to her daughter the same week that she graduated from college, and this solidified her commitment to teaching Ojibwe at the early childhood level.

“Early childhood is the prime time for language acquisition – their brains are more susceptible,” she says. “My daughter doesn’t struggle with verb conjugations the way I do. They don’t have to think so much to find the right words.”

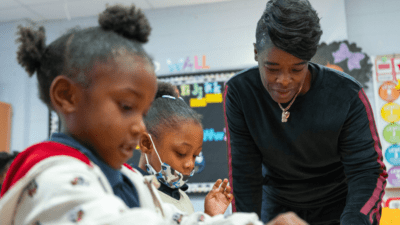

Khaloni Freemont interns with Wicoie Nandagikendan and is working on her early childhood education certification. She grew up in Minneapolis’ Little Earth neighborhood, a 9.4 acre development whose residents represent 38 different Tribal affiliations. Freemont’s first language was Ojibwe, but when she started school the district placed her in an English Language Learning program and expected her to primarily speak English.

“Our languages are dying,” she says, adding that everyone at Wicoie Nandagikendan is a language ambassador. “Our kids are learning it, so parents are learning it. And, I take the language everywhere. I take the language to my youth group and my drum and dance group. A lot of people want to learn.”

Just as Arcoren and YoungBear-Tibbetts create space for their community, the Indigenous Early Learning Collaborative (IELC) created space for them. IELC is a program of WKKF’s grantee Brazelton Touchpoints. They bring together Indigenous educators from four places – including the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, Minneapolis, Seattle and Hawaii – to support each other in developing culturally-relevant early learning systems.

Arcoren says that when Wicoie joined the collaborative, IELC’s project director Tarajean Yazzie-Mintz tuned into Minneapolis’ needs immediately.

“We joined right on the heels of the Chauvin verdict. We had a horrendous couple of years,” recalls Arcoren. Wicoie Nandagikendan’s classrooms and administrative offices are located in the heart of where the 2020 uprising took place. “We were living with the energy surrounding George Floyd’s murder, living in a food desert with everything boarded up, homeless encampments exploding due to COVID. We had a lot to process collectively and as individuals. We were reeling.”

Yazzie-Mintz sent two facilitators to Minneapolis to hold a retreat and ceremony for the Wicoie team. “It was amazing not to have to educate our [IELC partners] around our social, political, environmental issues,” says Arcoren. “They already knew.”

The facilitators invited the team to write out all the traumas they’d experienced in the previous 18 months. “Until then, I hadn’t written down the things that I experienced or spoken about them to anyone,” says YoungBear-Tibbetts, who provided street medic services to protestors after the murder of George Floyd in 2020 and other high profile police murders in 2021.

These necessary healing experiences rejuvenated the focus of Wicoie’s team on community and children’s well-being; well-being that is strengthened through community inquiry, building the future together, and revitalizing language and culture. As intern Khaloni Freemont points out, “There is no hate in our language. A lot of kindness and love comes from our words.”

Read More about the Indigenous Early Learning Collaborative

- Every Child Thrives, “We walk together for early childhood care & education“

- Every Child Thrives, “Revitalizing Indigenous early learning systems“

Comments