During the pandemic, many people in the metropolitan Detroit community worried about finding food.

“It was just mayhem at the very beginning,” said Gerry Brisson, president and CEO of Gleaners Community Food Bank (Gleaners). “At one of our mobile distributions early on, this woman came up to get food and she was just sobbing … because she literally couldn’t get food at the grocery store, and she didn’t know what to do. … We were able to help her and get her the food she needed, and she was just so relieved that starvation was not going to be her story. I’ve been involved in this work for 35 years. …People have been worried about missing meals and being hungry for a long time. But being worried about starving? I’ve never seen that before.”

Accessing healthy food, even before the pandemic, is a challenge for many families in Detroit, where 54% of children live in poverty. The city’s population is nearly 80% Black and nearly 94% people of color. Systemic racism has created barriers and obstacles for many families trying to access the resources they need to be healthy, including fresh, healthy food.

Within Detroit Public Schools Community District (DSPCD), the city’s main school district serving more than 53,000 of its children, 78% of students qualify for free or reduced lunch. Before the pandemic, DPSCD served more than 85,000 healthy meals to the district’s students each day: free breakfast and lunch for all students, a healthy snack for kids in grades K-8 and a summer food service program and dinner for schools with after school programs. The district also worked to get fresh foods to children and operates one of the largest urban farms in the city, as well as 80 school gardens.

When DPSCD had to close its buildings due to the pandemic in March 2020, making sure students had access to nutritious meals became an urgent concern, especially for the 3,000 medically fragile students and siblings.

“In one day, it was cut off. We knew that would be problematic,” said Machion Jackson, assistant superintendent of operations for DPSCD. “It seems light years ago, but I recall being very nervous and worried about what would happen to the children. This was an indefinite closure. How are we going to attend to them?”

Drastic increase in scope

Ensuring food was available to their families required DPSCD and Gleaners, both WKKF grantees, to drastically rethink how they deliver programs and to scale up very quickly.

DPSCD held countless meetings. They initially planned to distribute hot breakfasts and lunches each day at 57 of their 106 schools in neighborhoods throughout the city. But the health department quickly weighed in and told them they didn’t want people leaving their homes to pick up breakfast and lunch each day.

“We were able to quickly pivot, and by March 23, we changed our model, and we also reduced the number of sites, moving from 57 sites to 20 sites,” Jackson said. “And we also changed the model of distribution to distribute food that would serve as meals for multiple days. …On Mondays, we packaged meals for three days and on Thursdays, we packaged meals for four days. So, we moved from five days a week to seven days a week of providing our families with meals.”

Gleaners also shifted gears and scaled up rapidly.

In a normal year, Gleaners distributes an average of 40 million pounds of food in the metropolitan Detroit region. It serves as a logistical hub for more than 600 partners to dispense food that would otherwise go to waste by gathering it from the government, farms, retail companies and food packagers, making it available on a real-time inventory system and then sending it to agencies that feed people.

“As a central player in connecting a lot of different partners, we were called on to set the stage,” Brisson said. “The United Way called me within two days of the schools closing and asked ‘What do we do? How do we even imagine the food needs of the community?’ …Everybody in our partner network really came together. Within 10 days, we had a whole new distribution network developed. We had 65 mobiles (drive-up distribution sites), the schools we could still work with we worked with, and we hired 90 people in two weeks. It was a massive reinvention. …We had relationships with both funders and communities so that we could be the catalyst for contactless distribution.”

During the busiest 12 months of the pandemic, Gleaners distributed more than 80 million pounds of food – double their normal output.

Solutions created

Both DPSCD and Gleaners were able to meet the dramatic increase in demand. But they still ran into challenges they had to solve. For starters, like everyone else, they struggled to access COVID tests and personal protective equipment.

At DPSCD they also had to move equipment and people around to different buildings to handle their new supply chain, and struggled initially to find enough packaging materials to pack all of the meals.

While most parents were able to come to the sites to pick up meals, parents of medically fragile children could not.

“What’s going to happen to these children when their parents have to leave them at home to go out and get a meal for them and their siblings?” Jackson said. “The children would be endangered. Or they won’t be able to get food. Many of these families don’t have vehicles they can use to transport these children.”

So, the district leveraged their relationships with yellow bus companies. They turned five of their distribution sites into anchors for the medically fragile deliveries and used 15 yellow busses to deliver meals directly to the homes of medically fragile families.

Gleaners also knew they had to rethink everything. Pre-pandemic, to manage demand, the food bank and pantry system required people to make appointments to visit a food pantry, and 80% of those appointments were between 11 a.m. and 2 p.m. They knew that wouldn’t work during the pandemic.

“Before the pandemic, in 45% of all appointments made to a pantry to get food, people don’t show up,” Brisson said. “We knew right away we couldn’t manage this by appointment. We needed to just let people come. And not just us – our entire network of partners just allowed people to come, no appointments anywhere.”

They also worked with their network to make the hours of operation more flexible. They began tracking attendance to follow the need by tracking who showed up at what location at what time. Given the combination of this new tracking system for need, their real-time inventory system and their strong relationships within the food supply chain, Gleaners and its partners were able to pivot to meet the need.

“This is where I really felt like the system that is set up to communicate with partners worked really well,” Brisson said. “Our partners could agree to support communities because we could assure them we would have the food. The lead times for food went from three weeks to 12 weeks. But we were already ordering months ahead, so we only had to make minimum tweaks and then become flexible to make substitutions. …We could deliver on our promises.”

Prior to the pandemic, food banks and pantries had begun providing choice to people struggling with hunger. They remade pantries to look like grocery stores so people could come and pick out what they wanted. Tracking what people had chosen prior to the pandemic also helped.

Where they’re going from here

Most importantly, the pandemic taught DPSCD and Gleaners that their strength lies in their people.

DPSCD is developing plans to recognize their staff for the sacrifices they make to support children in Detroit.

“It’s so important to invest in your talent and human capital,” Jackson says. “Even if that level of investment isn’t monetary – you’ve got to create appreciation for the people doing the work and recognize them in some way. Embrace the heart. …Everyone was being paid, whether they stayed home or not. These people actively came out and worked and sacrificed and we have to celebrate them for their meaningful contributions.”

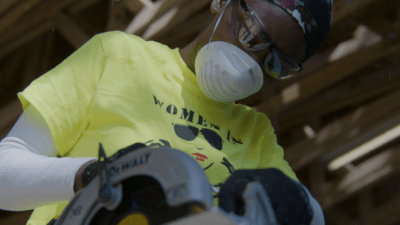

Part of that recognition has shown up in the way the district handled staffing for food services during the pandemic. People working in those roles are more vulnerable because they are paid less than other staff. DPSCD developed a two-team system to help protect people’s health and safety and to help staff manage the trauma of the pandemic and the work that needed to be done.

“We started hearing about someone having a family member passing,” Jackson said. “Soon it was neighbors and close friends and family connections. Our people needed time to grieve. They all needed time to mentally process the new way of working and what was going on in the world. We gave them that time. And we were successful as the result. We didn’t have to shut down food service because of poor staffing. …That is what allowed us to be successful and to serve well over 2 million meals.”

For Gleaners, moving forward, they’re considering what they’ve learned from their clients and their staff as they think about how to deliver a better food distribution system.

“The safety net has never met the need of the community for food,” Brisson says. “When we scrapped the appointment system during the pandemic, our partners and we were worried we’d be inundated. We didn’t want to have huge lines of people who were angry. Or people waiting for a long time to then get nothing because we’ve run out of food. But we learned that when we didn’t have any limits in place, on average families came twice a month. The respect people had for the system of only coming to get what they needed – they were incredibly conscientious. What we’ve learned will help us determine if appointments should be resumed in the future, or if they’re no longer necessary.”

Gleaners is also exploring how to remove other barriers to get people food. They want to help people avoid feeling shame when they need help, want to keep the system convenient and want to expand access to the fresh, healthier food people want most. So, they’ve worked with partners to start three Fresh Market Pantries to dramatically increase people’s access to fresh, healthy food.

In addition, Gleaners is working toward achieving racial equity in food security. Their board has created a diversity, equity and inclusion policy statement. They’re also working with the Michigan Roundtable for Diversity and Inclusion to develop a Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Justice Council, a permanent staff committee comprised of a cross-functional team that will listen to the community and set priorities for the organization.

“We have a lot to learn,” Brisson said. “Even about broad questions like if the safety net is important, how much should be food distribution versus SNAP dollars? How do you take into account government programs that help people this way and food programs that help people that way, and managing the right cost and outcomes for that activity? And then, you need to do that in light of what people really want and need and making sure people have equitable access. …We want to create a continuous learning organization where we don’t assume what we know today is right tomorrow.”

Comments